Unit 3 Introduction: Cities, Societies, and Empires

There’s no law that says that people must live in states. There’s nothing that says states must be divided into cities. There’s also not a solid reason that people in states and cities need to be farmers or to trade with others in farming-based places. But, these four things usually happen together. This unit will explore why and how they are connected.

There are many reasons why the history we study tends to focus on agrarian cities and states. For example, history tends to be written by people in cities and states that are centers of farming and trade. Those cities and states are usually places where people exchange ideas and create, so they tend to seem like important historical centers.

However, a lot happened during the period we’re covering in Unit 3—and even after—in societies that weren’t states or cities, didn’t farm, and weren’t trade centers. We’re going to learn about some of these societies too. But, because changes in these societies were usually slower, we’re going to spend more time talking about how trade grew, cities developed, and states formed. These changes really shaped how humans live, connect, and create.

Village networks

By 6000 BCE, humans had spread from Africa across most continents and islands. Some communities engaged in farming and animal herding, while others continued to forage and hunt. These groups adapted to their environments, developing specific strategies and tools.

Innovation was often pushed forward by changes in the environment. But, just as often, it came about because societies exchanged things with each other. New techniques, ways of doing things, ideas, and tools were usually created in one place. Then, they were shared with other societies through trade, fighting, and marrying into other groups. When societies met, they often copied their neighbors or changed the new ideas to fit their own needs. Some of the biggest inventions in human history—like iron and boba tea—were made only once or twice on their own. Then, they spread through networks around the world as new groups learned to use and enjoy them.

At this time, local networks were vital for daily life. Agricultural villages and nomadic groups formed connections, specializing in certain products to trade with others who had different goods. This exploration of community types and their trade and interaction networks reveals the complexity of early human societies.

Long-distance trade

Trade networks started out local, but they didn’t stay that way. In every world region, long-distance trade networks moved goods, people, and ideas, and as cities emerged, a new type of network developed—the metropolitan network. These networks connected cities with the villages and rural areas around them, which they could control to some degree because of their larger population.

Then, even larger trade networks developed in many places. In Eurasia, the domestication of horses allowed for much speedier communication and helped rulers extend their influence and control over people hundreds of miles away from the capitals of their empires. Similarly, the domestication of the camel in western Asia and Africa meant that people and goods could now move across deserts at an accelerated rate. Llamas came to play a similar role in some parts of the Americas.

At sea, new and better ways to build ships and navigate helped trade cover larger areas. In places like the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, and the Baltic seas—and later the Pacific Ocean—big networks of trade depended on the skills of communities that were good at building ships and sailing (or rowing). On land, technology also started to make a big difference. In many places, projects like building roads connected people in more efficient ways. Because of this, more people traveled—although the number of travelers was still small compared to the total number of people. But for those who did travel, they learned new languages, read new ideas, and shared those ideas with others in new places.

Cities

Cities and trade have a “which came first, the chicken or the egg?” situation. Cities often started around markets, where traders from different areas were already meeting. However, the growth of cities also encouraged more trade. This is because people in cities had extra wealth, like coins, food, or goods. They wanted to spend this wealth on luxury items that made their lives better.

Cities appeared at different times across the world. The very first cities might have been in places like Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, about 6,000 years ago. In regions like China, India, and Southeast Asia, cities began to form 5,000 years ago. Then, another period of city-building occurred from 4,000 to 2,500 years ago in areas such as Mesoamerica, the Andes mountains in South America, the Mediterranean Basin, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Cities were established for various reasons. Some were positioned to benefit from trade routes, others were built for defense, some for religious gatherings, and others served as government centers. These cities were often part of agrarian societies, where farming created a surplus of food. This surplus was necessary to support the soldiers, priests, builders, and other specialists that cities required. Yet, there wasn’t just one way to form a society or a city. Each community, whether it was Shang Dynasty China, Nubia, Chavín de Huántar, Aksum, Nok in West Africa, the Indus River Valley, or Mesopotamia, developed its own unique structure and way of life.

One thing these societies did have in common—and foraging communities probably didn’t have at all—was that each society had a wealthy group of people. Usually, the wealthy were a small group, and most people in cities were, by comparison, poor. This poor majority worked hard and suffered from diseases due to the concentration of people, animals, and excrement that cities produced.

States

Long-distance trade brought huge wealth to a small number of people. These “elite” classes had privileges and power, thanks to their control of money and resources. To protect those privileges, elites began the development of the state—rules, laws, government structures, and military that protected all citizens, but especially the wealthy ones. In their pursuit of power and wealth, elites could drive states to undertake violence and war at scales never before seen in human societies.

Trevor Getz

Trevor Getz is Professor of African History at San Francisco State University. He has written eleven books on African and world history, including Abina and the Important Men. He is also the author of A Primer for Teaching African History, which explores questions about how we should teach the history of Africa in high school and university classes.

Image credits

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0 except for the following:

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0 except for the following:

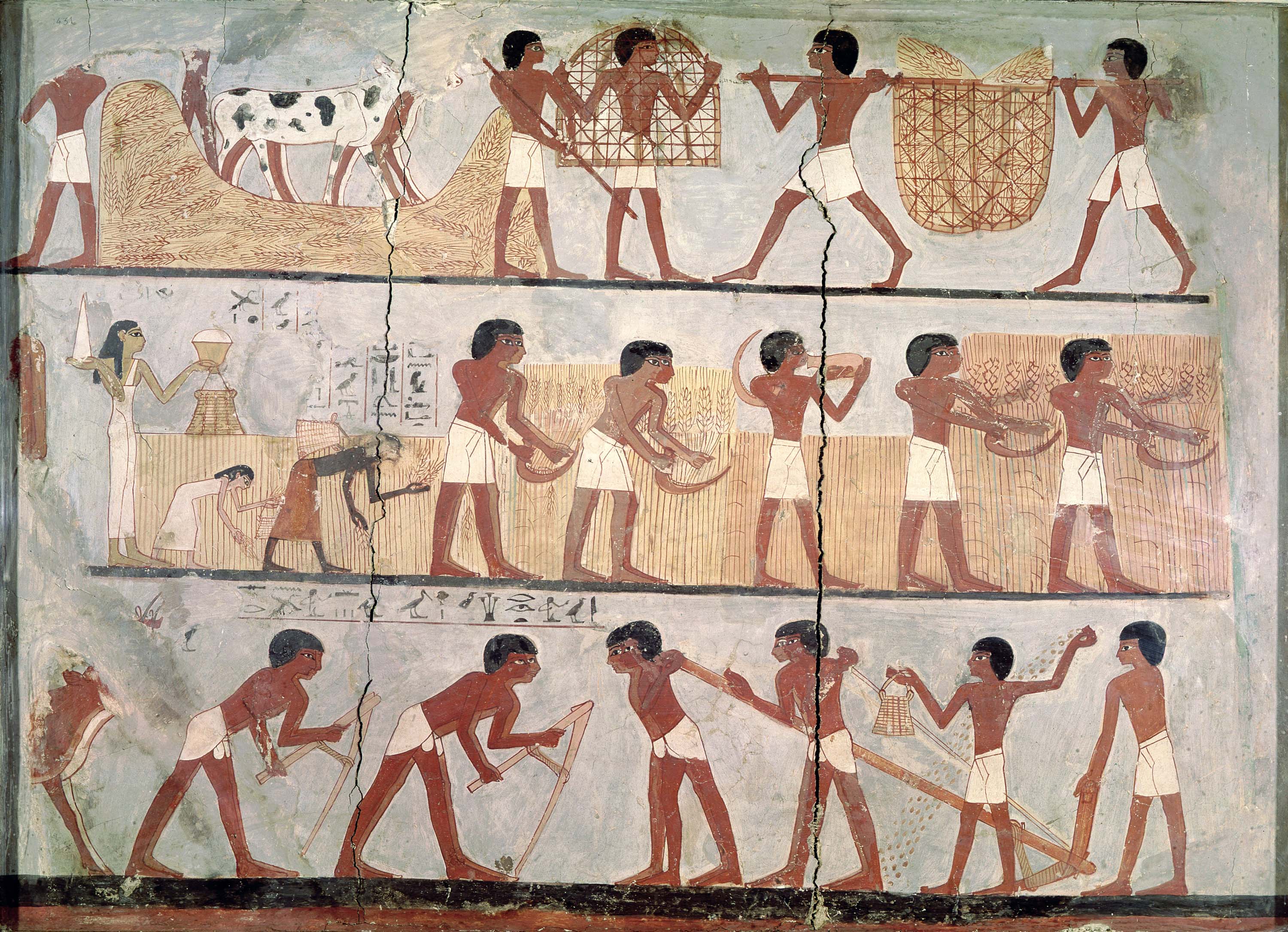

Cover image: Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty Wall Painting of Agricultural Scenes from the Tomb of Unsou. Courtesy of The Gallery Collection/Corbis.

Iron, so key to agriculture, was the result of a very sophisticated technique that was probably only developed twice in human history—in Anatolia and West Africa—and then spread around the world through trade. Courtesy The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1982-0103-308

A modern view of the central plaza in the city of Teotihuacan, which formed a nexus for trade routes in Mesoamerica. By Rene Trohs, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Panoramic_view_of_Teotihuacan.jpg

Chavín de Huántar, in modern-day Peru. This is the interior hallway of a temple in a design totally unique to the area. By Martin St-Amant, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chav%C3%ADn_de_Huantar_Ao%C3%BBt_2007_-_Corridors_Int%C3%A9rieurs_1.jpg

The “War Panel” of the Standard of the City of Ur, c. 2600 BCE. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_of_Ur#/media/File:Standard_of_Ur_-_War.jpg

Articles leveled by Newsela have been adjusted along several dimensions of text complexity including sentence structure, vocabulary and organization. The number followed by L indicates the Lexile measure of the article. For more information on Lexile measures and how they correspond to grade levels: www.lexile.com/educators/understanding-lexile-measures/

To learn more about Newsela, visit www.newsela.com/about.

The Lexile® Framework for Reading evaluates reading ability and text complexity on the same developmental scale. Unlike other measurement systems, the Lexile Framework determines reading ability based on actual assessments, rather than generalized age or grade levels. Recognized as the standard for matching readers with texts, tens of millions of students worldwide receive a Lexile measure that helps them find targeted readings from the more than 100 million articles, books and websites that have been measured. Lexile measures connect learners of all ages with resources at the right level of challenge and monitors their progress toward state and national proficiency standards. More information about the Lexile® Framework can be found at www.Lexile.com.