Unit 2: Liberal and National Revolutions

1750 – 1914 CEThe old world order started to unravel as radical ideas took hold. Explore how revolutionaries and nationalists challenged authority—and reimagined what nations could be.

Ingredients for Revolution

Lesson 2.2

The Enlightenment

What if reason—not tradition—was the best guide for how to run a society? Enlightenment thinkers asked bold questions that changed how people saw power and rights, and the world is still grappling with the answers they proposed.

Lesson 2.3

What Causes Revolutions?

No single cause explains every revolution. Some begin with ideas while others start with hunger, injustice, or fear. Understanding why they happen means asking deeper questions about power and possibility.

Liberal Revolutions

Lesson 2.4

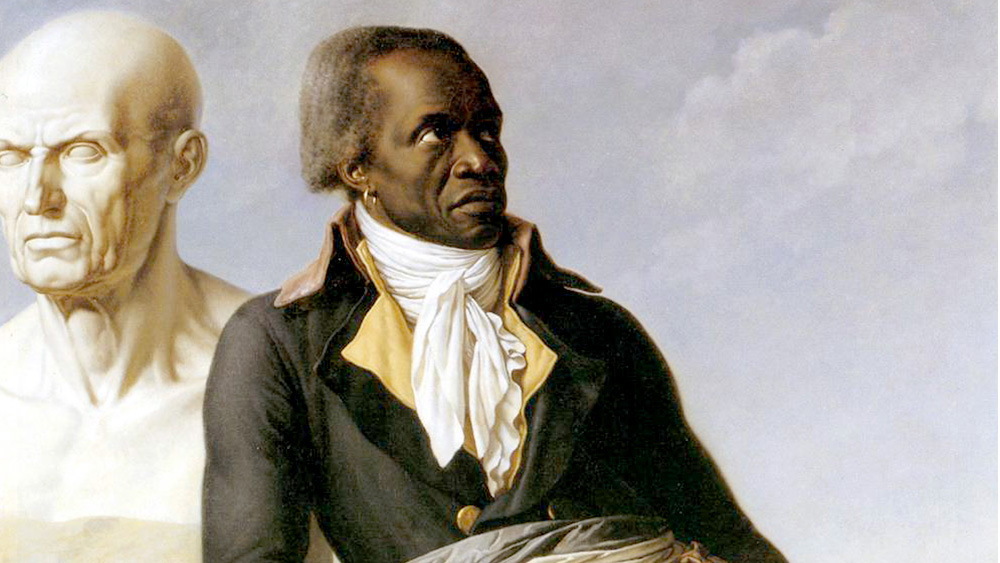

Atlantic Revolutions

The age of revolution wasn’t limited to one place or one story. The revolutions of the Americas, France, and Haiti were linked by shared ideas about freedom, but each movement had its own goals and its own struggles.

Lesson 2.5

An Age of Revolution?

Not all revolutions delivered what they promised. Comparing them shows just how complicated the idea of revolution can be.

Nationalism

Lesson 2.6

Origins of Nationalism

As people challenged old rulers, new ideas about belonging began to take hold. Nationalism helped people imagine communities that went beyond kings, empires, or borders.

Lesson 2.7

Nationalism Spreads

Nationalism spread like wildfire during the long nineteenth century, from Europe to Asia, leaving a legacy of successes and failures in its wake, and radically transforming the world.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 2 Vocab

Key Unit 2 vocabulary words and definitions.

Reading Guide

Explore the types of texts in OER Project.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Writing Guide

Strategies for instructing and supporting both formal and informal writing.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.

Unit 2 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.