Liberal and National Revolutions

Teacher Resources

Driving Question: How did nationalism and sovereignty reshape the world in the long nineteenth century?

It might seem like nation-states—with flags and laws and borders—have been around forever. But most actually got their start almost 300 years ago. After 1750, revolutions erupted around the world and new forms of government emerged, governments that were based on new ideas about sovereignty and the freedoms people deserve. These revolutions led to the first nation-states.

Learning Objectives:

- Learn about new ideas of sovereignty and how these ideas affected communities and nations.

- Evaluate how new ideas about sovereignty and individualism impacted communities in the Atlantic world.

- Understand the origin and effects of nationalism on human communities and political revolutions.

Vocab Terms:

- community

- liberal

- nationalism

- nation-state

- revolution

- sovereignty

Opener: Liberal and National Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 2 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Our Openers and Closers Guide will provide more information about these short-but-important activities at the beginning and end of each lesson.

As you may have guessed from its title, this unit is all about revolutions. So, what is a revolution? Look at some revolutionary song lyrics to consider the definition.

Looking Ahead

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Get an idea of how other teachers use Unit Notebooks by checking out this conversation in the OER Project Teacher Community.

Agree or disagree? Evaluate some statements before you dive into Unit 2—then see how accurate you were when you get to the end of the unit.

Liberal and National Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Check out our Reading Guide to learn about the Three-Step Reading approach.

Looking to differentiate, modify, or adapt this assignment? Check out our Differentiation Guide.

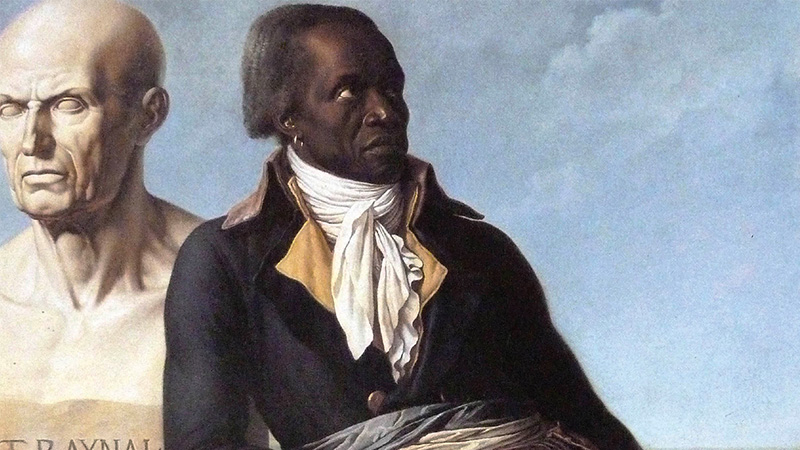

During the long nineteenth century, political revolutions were sparked by new ideas about rights. This video and article will introduce you to some of the causes and effects of these revolutions.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- What is sovereignty?

- Before 1750, who could participate in the government of most states around the world?

- How would you describe the big political changes that began in this period?

- What did the inhabitants of Saint Louis think of the French Revolution?

- What does the evidence suggest about the spread of democracy around the world since 1750?

After you watch

Respond to this question: How do concepts that emerged in this period—such as sovereignty and political rights—matter in your life today?

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you read

Preview the questions below, and then skim the article. Be sure to look at the section headings and any images.

While you read

Look for answers to these questions:

- In general, what were politics and government like around the world at the beginning of the long nineteenth century?

- What important new political ideas resulted from the Enlightenment?

- What is a revolution? Based on this introduction, which revolutions do you think you’ll be studying in this unit?

- What is nationalism, and what role does this author suggest it played in political revolutions?

After you read

Respond to this question: Did the revolution described in this article have any limits in who got to participate?

Framing Unit 2

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 5 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Looking to deepen your understanding of frames? Take a look at this conversation in the OER Project Teacher Community.

The frames can help us understand how the world transformed from a world of kings and subjects to a world of nation-states and citizens.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- What were some of the biggest communities in 1750?

- What other kinds of communities were important to people’s lives, c. 1750?

- What did almost everyone share in this period, whether they lived in a large empire or a smaller community?

- What were three new ideas about community that emerged in this period, according to this video?

- What new kind of community did these ideas help to create?

After you watch

Respond to the following question: Is the nation-state you live in the most important kind of community in your life?

Closer: Liberal and National Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 6 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Our Openers and Closers Guide will provide more information about these short-but-important activities at the beginning and end of each lesson.

Consider prompting your English-learner (EL) students to try translanguaging as they break down the meaning of “revolution” and “evolution”—that strategy and more ways to support all learners are covered in our Differentiation Guide.

Review what you’ve learned in this lesson by considering one of the key words of this unit—revolution.

Writing Prep: Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 7 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Learn more about writing in OER Project courses in the Writing Guide.

Practice claim writing while reviewing what you’ve learned by building a claim about liberal and national revolutions.