2.4 Was Farming a Good Idea?

-

9 Activities

-

5 Articles

-

2 Videos

-

1 Visual Aid

-

1 Assessment

Update ahead! This course will be updated soon. See what's changing.

Introduction

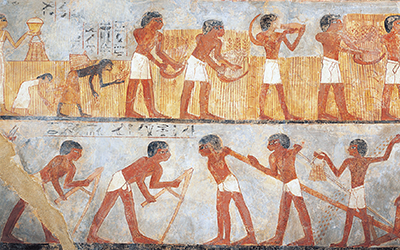

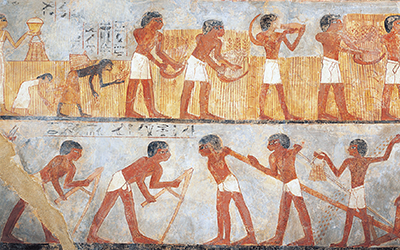

Over long periods of time, many things change, but other things continue as they were. This idea is as fundamental to the historian as gravity is to the physicist. With practices such as comparison and causation, you will start to identify continuity and change over time. The change from foraging to farming is among the most consequential events in human history – it’s why there are almost eight billion people alive today. Farming led to many new occupations – priests, soldiers, scribes – and to the building of bigger societies and states. But it also led to poorer diets, more disease, and longer working hours. So it is well worth asking, from as many perspectives as possible, whether farming made our lives better or just busier.

Learning Objectives

- Learn about the historical thinking skill of continuity and change over time and apply this concept to historical thinking and analysis.

- Evaluate why some human communities did not begin farming and how foragers, pastoralists, and farmers interacted.

- Analyze how farming led to state formation.

- Identify claim and focus in historical writing.

- Create and support arguments using historical evidence for why many early human communities made the switch from foraging to farming.

CCOT – Introduction

Preparation

Purpose

As you’ve learned, one of the main historical thinking tools that historians use to analyze and produce accounts of the past is comparison. In this activity, you’ll learn how to evaluate for continuity and change over time (which we’ll refer to as CCOT throughout the course) so that you have a method for comparing (and making claims about) how the same location, idea, or historical process either stayed the same or changed during a set time in history.

Practices

Comparison, causation

Continuity and change analysis involves comparison, but it’s different from the kind of historical comparison that you’ve been introduced to earlier in this course. Typically, historical comparison involves examining the similarities and differences between two things, while CCOT looks at how things stayed the same or changed over time. Comparison is often a component of a CCOT analysis. Additionally, part of understanding how and when a change occurred is related to understanding the causes and consequences of those changes.

Process

What are continuities? What are changes? How do these relate to history? We refer to continuities as the things that have stayed the same over time in history. And changes—which are often easier to identify—are the things that did not stay the same. Historians often do something called a continuity and change over time analysis (CCOT analysis for short). They do this by looking at how certain things changed or stayed the same over time. One of the reasons historians find CCOT analysis useful is that recognizing what has stayed the same helps them decide which changes throughout history were the most significant. This, in turn, allows historians to see how those changes may have led to major transformations in how people lived and continue to live today.

Instead of looking at an event or something that happened at a defined moment or time period, we are now trying to understand how farms, one of the mainstays of societies since the development of agriculture, have evolved. We are going to look at farms in the state of Iowa from the 1700s, 1800s, 1900s, and today, to determine how farms have changed and how they’ve stayed the same over time.

Your teacher will either hand out or have you download the CCOT – Introduction worksheet. Glance at the pictures of the four farms on the first few pages. Based on just the images, discuss as a class what is the same and what is different about the four farms. Remember that the things that are the same are continuities. And the things that are different are, you guessed it, changes!

Now, you’ll review the CCOT Tool portion of the worksheet with your class. As with sourcing, claim testing, and reading, there is a tool that you can use to help you analyze continuities and changes. Working in small groups, write down on the tool portion of the worksheet the timeframe with which you’re working. Then, read through the text accompanying the images of farms and write the continuities and changes you find on your sticky notes (one continuity or one change per sticky note).

Next, place your sticky notes on the graph (either using the graph in your worksheet or by drawing the graph on the board) and decide whether your continuities and changes were positive or negative. Be prepared to explain your reasons for categorizing your continuities and changes as either positive or negative.

Once your group has placed all your sticky notes on the graph, answer the remaining questions on the tool. In the last set of questions, you’ll be evaluating the most significant change and continuity. You can use the acronym ADE (amount, depth, and endurance) to help you determine historical significance. You’ll decide if the changes and continuities affected all people (amount); if the changes and continuities deeply affected people (depth); or if the changes and continuities were long lasting (endurance). Be prepared to share your most significant continuities and changes with the class.

Your teacher will collect your worksheets and use them to assess your understanding of this historical thinking practice. And remember, this is a just a simple exercise to get you used to the idea of CCOT. It’s going to get a lot more complicated as you move through the course and increase your historical knowledge!

EP Notebook

Preparation

Make sure you have the EP Notebook worksheets that you partially filled out earlier in the era.

Purpose

This is a continuation of the EP Notebook activity that you started in this era. As part of WHP, you are asked to revisit the Era Problems in order to maintain a connection to the core themes of the course. Because this is the second time you’re working with this era’s problems, you are asked to explain how your understanding of the era’s core concepts has changed over the unit. Make sure you use evidence from this era and sound reasoning in your answers.

Process

Fill out the second table on your partially completed worksheet from earlier in the era. Be prepared to talk about your ideas with your class.

The Transition to Farming: Differing Perspectives

Vocab Terms:

- adopt

- agriculture

- forager

- intensive farming

- network

- scattered farming

Preparation

Summary

The shift from foraging to farming by our ancestors was gradual, uneven, and revolutionary. Farming changed the way communities were organized, expanded and shrank networks, and made way for new systems of production and distribution of goods. There are many possible reasons why early humans began to farm rather than stick to foraging. The debate continues around which method (farming or foraging) led to a higher quality of life for early humans. Regardless of which one was “better,” it’s no argument that the shift to farming was monumental for the future of humankind.

Purpose

This article provides much of the evidence to help you respond to the Era 2 problem, “What caused some humans to shift from foraging to farming and what were the consequences of this change?". It is also important for understanding the transition to farming as evidence for evaluating the production and distribution frame narrative.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What evidence does the author use to suggest that farming was an unintentional process to begin with?

- How did the rise of fixed farming communities change what people’s daily work looked like?

- According to the author, how did the rise of villages both expand and shrink networks?

- What were the benefits and drawbacks of foraging as a system of production and distribution?

- What were the benefits and drawbacks of farming as a system of production and distribution?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- Did this article support, extend or challenge your understanding of the communities, networks and production and distribution frames?

- Given the evidence in this article, would you have preferred to have been a farmer or a forager?

Farming and the State

Vocab Terms:

- alluvial

- farming

- hierarchy

- labor

- state

Summary

Did farming lead to the state? Were all states made by farmers, and did all farmers come to live in states? In this video, two leading world historians share what they know about the connections between the shift to agriculture and the rise of states.

Farming and the State (6:51)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video will introduce you to a debate about the connection between farming and the state. That connection is important to evaluating both the production and distribution frame and the communities frame. It will also help you to respond to the second half of the Era 2 Problem: What caused some humans to shift from foraging to farming and what were the consequences of this change?

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Before you watch the video, open and skim the transcript. Additionally, you should always read the questions below before you watch the video (a good habit to use in reading, too!). These pre-viewing strategies will help you know what to look and listen for as you watch the video. If there is time, your teacher may have you watch the video one time without stopping, and then give you time to watch again to pause and find the answers.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- What do Candice Goucher and Laura Mitchell think about the argument that farming was a pre-condition for the state?

- What evidence do Goucher and Trevor Getz provide as a counterargument to the claim that grain farming, in particular, leads to states?

- What does Mitchell say about the connection between labor and the state?

- Given the added labor and tax burden, do Goucher and Mitchell think the state was a good idea?

- According to Goucher, is there still a connection between farming and the state today?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- What does the relationship between farming and the state suggest about the relationship between the production and distribution and communities frame? In what ways are these frames related? In what ways are they different?

- This video concentrates on the connection between farming and the formation of states, many of which had some common characteristics such as social hierarchy and specialization of labor. But the participants also push back on this by stating that there were other states that did not rely on farming such as fishing populations or pastoralists. What about foraging communities—do you think some foraging communities could also be called states? What conditions might foragers need in order to develop things like specialization of labor or social hierarchies?

Causation – From Foraging to Complex Societies

Vocab Terms:

- categorize

- causation

- complex

- consequence

Preparation

MP4 / 11:10

Purpose

In this activity, you will continue to grapple with cause and consequence and explore how causal reasoning can be used to help understand change over time. Causal reasoning can help you develop evidence-based explanations or arguments in response to a question that considers human actions, events, and larger structures or processes. You will think about both the causes and consequences of farming, which will push you from thinking about causation as linear, toward an understanding of the complex relationship between cause and consequence.

Practices

Claim testing

Causation requires a great deal of sound reasoning, which is another way of saying claim testing. In order to identify and best categorize causes and consequences, students have to use logic, evidence, and (usually) authority.

Process

In this activity, you’ll first identify the factors that might have caused early humans to switch from foraging to farming. If you need to refresh your memory on the transition to farming, review the video The Agricultural Revolution: Crash Course World History, along with these articles: “The First Farmers in Africa, the Cradle of Humanity” and “The Transition to Farming: Differing Perspectives.” Next, you’ll think about the consequences that were the result of this transition, and you’ll construct a causal map that will put all of this into perspective. Historians use causal maps to help them organize historical events or processes. Creating a causal map allows you to see the connections between events over time. In addition, these maps will help you understand that causation is rarely linear.

First, your teacher will either hand out or have you download the Causation – From Foraging to Complex Societies worksheet, which includes the Causation Tool and causal map. Working together with your class, follow these directions:

- In the Event box, write the name of the event you’re studying, along with the dates, location, and a brief description.

- Using what you have learned so far in the course about why some early human communities began to farm, think of all the possible causes that led to farming. Your teacher will write these on the board.

- As you think about the causes listed, decide which should be categorized as long term, intermediate term, or short term. Make sure you’re able to justify your categorizations.

- Write each cause in the appropriate box of the worksheet (long term, intermediate term, or short term).

We’ll get to the other parts of the tool later in the course. For now, categorizing by time will be a sufficient way to understand these causes.

Your teacher will now divide you into small groups. With your group, look at the causal map for farming. Think about the following questions as you review the map:

- Are all the causes that were written on the board included in this causal map?

- Would you have organized this causal map differently? If so, how?

Now, try to think of all the possible consequences (effects) of farming and add them to your tool. Then, add those effects to your causal map. Fill in the circles on the map and add at least three more circles. Next, label your causal maps. For each circle that’s a cause, write the letter “C” next to it. For consequences/effects, write the letter “E” next to those circles.

Once you’re done, be ready to discuss with your class what you labeled as causes or consequences and which of those are the most historically significant. You can determine historical significance in several ways. Use the acronym ADE to help you determine if historical events or processes, in this case the causes and consequences of farming, were significant.

- Amount – How many people’s lives were affected by the cause/effect?

- Depth – Were people living in the time period being studied deeply affected by the cause/effect?

- Endurance – Were the changes people experienced as a result of this cause/effect long-lasting and/or recurring?

Your teacher will collect your worksheets and use them to assess how your causation skills are progressing.

Geography – Era 2 Mapping Part 2

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity you'll build on the geographic knowledge you developed in the Era 2 Part 1 map activity. This activity will help you identify and analyze maps to better understand how changes in early human migrations and agriculture shaped human communities. It will also provide additional evidence to help you respond to the Era Problem: What caused some humans to shift from foraging to farming and what were the effects of this change? In Era 3, you will learn about some of the ongoing consequences of agriculturalism on human societies. This activity will help prepare you to evaluate narratives surrounding those consequences in Era 3.

Process

This activity begins with an identification opening in which you’ll revisit and correct your labels of agricultural regions from the Part 1 activity you completed at the beginning of Era 2. Next, you’ll add a new layer to this map by tracing the routes of human migration and annotating the map about the agricultural revolution using evidence you encountered in Era 2. Finally, you’ll examine a map of ancient empires and agricultural regions as you write a response to a prompt about how the rise of agriculture changed human communities.

Step 1

In the Era 2 Part 1 map activity, you tried to identify the nine regions where agriculture arose independently at different times. Individually, you should take out the blank map you labeled in that activity. Then, review the Ancient Empires and Agriculture Thematic Map and correct your labels. Were your guesses for which areas developed agriculture earliest correct or close to correct?

Step 2

Once you’ve finished correcting your labels, your teacher will break you into small groups. Using evidence you encountered in Era 2, you should complete two tasks. First, trace the routes of early human migration across the world. Next, add two new annotations to the map about early human communities. This can be anything you found interesting or important in the era, but you should label the spot on the map where the event took place.

Step 3

Remaining in small groups, you should return to the Ancient Empires and Agriculture Thematic Map. Take a few minutes to examine the map and its legend. What information is contained in the map? Finally, your group should prepare a short paragraph or bullet list in response to this prompt (be prepared to share your answers with your class and teacher):

The emergence of agriculture was one of the most important changes in human history. Using this map and other evidence encountered in this era as evidence, how do you think farming changed human communities?

Writing – Claim and Focus Part 1

Preparation

Purpose

Being able to write clearly and convincingly—to write well—helps us communicate our thinking and conclusions. Writing well will help you in many areas of life, and being a good writer is a prerequisite for being a good historical writer. Throughout the course, your historical writing is assessed at the end of each era through a document-based question (DBQ). To help you become a better writer, we have included a series of rubric-based writing activities in this course. In this activity, you will learn more about the WHP Writing Rubric generally, and you’ll start to examine the areas of claim and focus more specifically as you begin your journey to become a more skilled writer.

Practices

Reading

You will read an article, and then identify its claim and focus. Each of the writing progression activities will involve some reading, which probably isn’t surprising, since reading and writing are often considered two sides of the same coin.

Process

Did you know that grammar can save lives? Take a look at these two images, and you’ll see why.

OK, these are silly, but they’re also a good reminder of why being able to write well is an important skill to develop. Throughout the course, you’re going to spend some time focusing on your writing skills. No, this is not your English language arts class, but being a writer who can communicate well is vital to being a historian. Most historians share their ideas through writing, and as student historians, you are asked to do the same. The next activity is a writing assignment, and it’s important that you understand what is expected of you when writing in this course.

Take out the WHP Writing Rubric and quickly review it. For this activity, you are going to pay close attention to the Claim and Focus section of the rubric. Review the criteria for claim and focus, and then think about the following questions and discuss them one by one with your class.

- What is a claim?

- What does a claim do in an essay?

- Why should we care about claims?

- What is a focused essay?

Once you’ve covered these concepts, review the article “The Chronometric Revolution,” which you likely read earlier in the course. First, find and circle the major claim in the article. Sometimes finding the claim is hard, and one thing that can help you identify it is to look at the focus of the article to help you figure it out. So, you’ll do that next. The best way to do this is to look for any ideas that are repeated over and over again. Any time you find repeated ideas, underline them. Your teacher may have you do this in pairs or small groups.

Once you are done, share your thinking with the class. Finally, would you give this article a grade of advanced, proficient, developing, or emerging based on the Claim and Focus criteria in the WHP Writing Rubric? Be prepared to share your thoughts and reasoning with your class.

Claim and Focus Warm-Up

Preparation

Carefully read the DBQ prompt you will be responding to. Be sure to have read and analyzed the documents prior to doing this warm-up activity.

Purpose

As you develop your close reading, critical thinking, and historical thinking skills, you also build writing skills that will help you in a lot of other classes. This warm-up explores the Claim and Focus row of the Writing Rubric and allows you to better understand those concepts and how they apply to thinking and writing.

Process

In this quick warm-up activity, you’ll practice using the language of an essay prompt to make a claim, provide focus for that claim, and then make a counterclaim. Your teacher might ask you to do just some of the steps in this activity, so be sure to listen for instructions.

Part 1 – Claim

What is a thesis or major claim in an essay? Discuss your ideas with your class.

How do we figure out how to write a thesis/major claim in response to a prompt? One way to do this is by turning the essay prompt/question into the stem of a statement, and then adding a little more information to make it a claim. Then, you can make an even stronger claim statement by getting even more specific. Work through an example of this with your class.

Then, repeat this process using the prompt you are getting ready to respond to.

Part 2 – Focus

What is focus in an essay? Discuss your ideas with your class and refer to the WHP Writing Rubric for more information.

How do you maintain focus in an essay? One way to do this is by linking back to key words and ideas from the thesis/major claim. Review the thesis/major claim from Step 1 and underline the key points that were included that you could write more about in the body of the paper. Then, work with your class to create three supporting claims that mirror the language or ideas from the original claim.

Now, do the same thing using the thesis/major claim you wrote in Step 1 in response to the prompt you’ve been assigned.

Part 3 – Counterclaim

What is a counterclaim? Discuss your thinking with your class.

How do you make a counterclaim? To weave a counterclaim into your thesis/major claim statement, ask yourself this: Who would disagree with your statement and why? What alternative or opposing viewpoints might you encounter when discussing this topic? Once you’ve considered other viewpoints, try weaving them in. Work through the following example with your class.

Now, create a counterclaim related to the prompt you will be responding to.

Once you’re done, you’re ready to write!

DBQ 2

Preparation

Era 2 DBQ: To what extent was farming an improvement over foraging?

Have the Comparison, CCOT, and Causation tools available (find all resources on the Student Resources page)

Purpose

This assessment will help prepare you for the document-based questions (DBQs) you will probably encounter on exams. It will also give you a better understanding of your skills development and overall progress related to constructing an argument, interpreting historical documents, and employing the historical thinking practices you are using in this course.

Practices

Contextualization, sourcing, reading, writing

All DBQs require you to contextualize, source documents, and of course as part of this, read and write.

Process

Day 1

In this activity, you are going to prepare to respond to a DBQ, or document-based question. In this course, document-based questions give you a prompt or question along with seven source documents, and you’ll use the information in those documents (and any additional knowledge you have) to respond to the prompt. Your responses will be written in essay format, and will usually be five or six paragraphs long.

This DBQ asks you to respond to the following prompt: To what extent was farming an improvement over foraging? To make sure you’re clear on what you’re being asked, take out the Question Parsing Tool. Work with your classmates to deconstruct the prompt.

Next, take out the DBQ and relevant thinking tool to help you analyze the documents. Take a look at the document library. As you do with the Three Close Reads process, quickly skim each of the documents for gist. Then, do a closer read of each one. For each document, write down the information you think you might use in your essay. If possible, also provide a source analysis for each document. Write your ideas on the relevant tool as you work through the documents. Discuss your ideas with the class.

Now, come up with a major claim or thesis statement that responds to the prompt. Use the information from your thinking tool to help you come up with an idea. What you have written should help you support your claim. One common mistake students make when responding to a DBQ is not directly answering the prompt—so, in creating your thesis, make sure that it directly answers and is relevant to the prompt.

Finally, it’s time to contextualize. Remember, that ALL historical essays require you to contextualize. If you need to refresh your memory, contextualization is the process of placing a document, an event, a person, or process within its larger historical setting, and includes situating it in time, space, and sociocultural setting. In this case, you are contextualizing the documents. Contextualization will often come at the beginning of your essay, or at least in the first paragraph, either before or after your thesis statement. As needed, you can use the Contextualization Tool for this part of the process.

Day 2

This second day is your writing day. Feel free to use your tools and notes from any prewriting work you completed as you craft your essay response. Make sure you have a copy of the WHP Writing Rubric available to remind you of what’s important to include in your essay. And don’t forget to contextualize! In doing that, think of the entire time period, not just the time immediately preceding the historical event or process you are writing about. Your teacher will give you a time limit for completing your five- to six-paragraph essay responding to the DBQ.

DBQ Writing Samples

Preparation

Purpose

In order to improve your writing skills, it is important to read examples—both good and bad—written by other people. Reviewing writing samples will help you develop and practice your own skills in order to better understand what makes for a strong essay.

Process

Your teacher will provide sample essays for this era’s DBQ prompt and provide instructions for how you will use them to refine your writing skills. Whether you’re working with a high-level example or improving on a not-so-great essay, we recommend having the WHP Writing Rubric on hand to help better understand how you can improve your own writing. As you work to identify and improve upon aspects of a sample essay, you’ll also be developing your own historical writing skills!

Claim and Focus Revision

Preparation

Have your graded essay ready to use for annotation and revision purposes.

Purpose

The purpose of this activity is to show you how to use a rubric-aligned tool to evaluate and improve upon a piece of writing. A useful strategy for improving writing skills is to analyze samples as an editor, using peer drafts or your own graded essays. As you think critically about the criteria in the WHP Writing Rubric and evaluate a piece of writing against it, you will continue to build your understanding of what makes a piece of writing strong. This, in turn, will make your writing stronger.

Process

In this activity, you’ll first review the Claim and Focus row of the WHP Writing Rubric with your class if you have not already done so. Then, you’ll be introduced to the Claim and Focus Revision Tool and how you to use it to improve upon claim and focus in an essay. Finally, you’ll use the tool to evaluate and revise an essay.

If you are reviewing and discussing the Claim and Focus row of the rubric with your class, remember that a strong thesis/major claim and subclaims will help establish good focus in an essay.

Next, take out the Claim and Focus Revision Tool. First, pay attention to the directions at the top, which ask you to review the prompt for the essay. Review a prompt with your class and underline all the key words in the prompt that relate to what specifically is being asked of the writer. This will help you focus your review on what was specifically asked for in the essay. Next, review the feedback received from your teacher or peers to get a better sense of how the essay fared in terms of claim and focus. This will help give you a general sense of where improvement is needed.

Finally, it’s time to use the table portion of the tool to really start digging into the details of the essay as they relate to claim and focus. This part of the tool is broken into three steps. The first step addresses claim, the second step addresses focus, and the third step addresses counterclaim. Within each step there is a review and revision process. For the review process, look at the checklist under the Review column and see if you can find those elements of writing in the essay. If you find them, check the box and move to the next item in the list. If you didn’t find them, look to the Revision column for suggestions about how to improve that aspect of the essay. Go through each item on the checklist so that you are prepared to revise for claim, focus, and counterclaim in the essay where needed.

Now that you have an idea of how the tool works, it’s time to try this out on your own!