Unit 2 Overview

Teacher Resources

Driving Question: How did networks of exchange connect societies, and how were communities changed by these connections?

Why start a world history course in 1200 CE? This lesson provides important historical context for how the world was organized before it became globally connected. Learning about the variety of communities and networks that existed from 1200 to 1450 CE will also allow you to make historical comparisons across time and geographic space.

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the major similarities and differences in how communities were organized from 1200 to 1450 CE.

- Explain how communities interacted through regional networks from 1200 to 1450 CE.

- Identify the major changes and continuities in the three frames from 1200 to 1450 CE.

Vocab Terms:

- belief system

- culture

- dynasty

- empire

- maritime

- society

- state

Opener: Unit 2 Overview

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 2 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Looking to do more with maps? Check out OER Project’s collection of maps here.

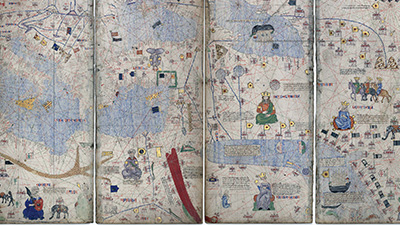

What can a map with some circles tell you about the world in the thirteenth century? Put your hypothesis skills to the test!

Looking Ahead

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Get an idea of how other teachers use Unit Notebooks: Check out this conversation in the OER Project Teacher Community.

Agree or disagree? Evaluate some statements before you dive into Unit 2—then see how accurate you were when you get to the end of the unit.

The Global Tapestry

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Check out our Reading Guide to learn about the Three-Step Reading approach.

We accept our various global connections as part of our everyday lives. But exactly what were the origins of these ties that bind us? The video and article below will give you a glimpse into how the world was organized from c. 1200 to 1450 CE.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- What two factors permitted the expansion of networks in this era?

- What does the data on global GDP tell us about this era?

- How did the expansion of trade to East Africa change the cities of the Swahili Coast?

- What is the evidence that the Swahili city-states brought together different worlds?

- What were some of the consequences of new interconnections and expanded networks?

After you watch

Respond to this question: This video uses global historical GDP as evidence to argue that trade increased during this era. Do you agree with this claim? What are some other kinds of evidence that could be used to show increases or decreases in trade and interconnection?

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you read

Preview the questions below, and then skim the article. Be sure to look at the section headings and any images.

While you read

Look for answers to these questions:

- Why does this course start around 1200 CE?

- What three big zones help to structure this unit?

- What frame does the author suggest is most useful for comparison within and between these zones?

- Why did people want or need goods produced in different regions?

- What were some of the consequences of long-distance connections within zones of the world?

After you read

Respond to this question: Why do you think the author makes such a big deal of the fact that societies in this period were different and diverse, and that many were connected to each other and shared ideas and technologies?

Framing Unit 2

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 5 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Looking to deepen your understanding of frames? Take a look at this conversation in the OER Project Teacher Community.

Interesting things happen when people from diverse cultures and regions get together. This lesson examines how developments such as new trade routes changed the lives of so many.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- What did the world generally look like from 1200 to 1450?

- What mighty empire emerged early in this era and what territories did it include?

- In what ways did large empires allow for the creation and expansion of long-distance trade routes, and how did these routes transform societies?

- What major event occurred between 1346 and 1351, and what were the consequences?

- What are three important technologies that spread during this period?

After you watch

Respond to the following question: The video makes the claim that in history, nothing happens in a straight line. Can you think of an example to help explain what this statement means?

Closer: Unit 2 Overview

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 6 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

For more information about why OER Project uses closers in every lesson, check out our Openers and Closers Guide.

A lot of new information has been presented over the course of this lesson! How would you summarize it?

Claim Writing and Networks

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 7 of the Lesson 2.1 Teaching Guide.

Learn more about OER Project’s approach to writing in the Writing Guide.

Practice claim writing while reviewing what you’ve learned by building a claim about trade networks.