Revolutions

Teacher Resources

Driving Question: How did people transform the political systems under which they lived, and were these changes felt equally around the world and within communities?

Revolutionary ideas emerged as individuals began to feel social and political inequalities. Enlightenment thinkers played a crucial role in shaping those revolutionary ideas. The combination of new thinking, economic inequality, and political grievances sparked movements that toppled kings and built a world of nation-states.

Learning Objectives:

- Analyze the roles sovereignty, individualism, and equality played in political revolutions.

- Use the course frames to evaluate how revolutions reshaped human communities in the long nineteenth century.

Vocab Terms:

- capitalism

- democracy

- govern

- liberal

- nation-state

- revolution

- right

- sovereignty

Opener: Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 2 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

Check out “You say you want a revolution” How do you make connections? in the Community forum for a ton of ideas about how to teach this activity and others in this unit.

As you may have guessed from its title, this unit is all about revolutions. So what is a revolution? Look at some revolutionary song lyrics to consider the definition.

Looking Ahead

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

Review the OER Project Writing Guide to learn more about why informal writing is so important in our courses.

Agree or disagree? Evaluate some statements before you dive into Unit 4—then see how accurate you were when you get to the end of the unit.

Revolutions: 1750 to 1914

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 3 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

Want to make sure students are engaging academically with videos? Take a look at the OER Project Video Guide for some great ideas on how to do this!

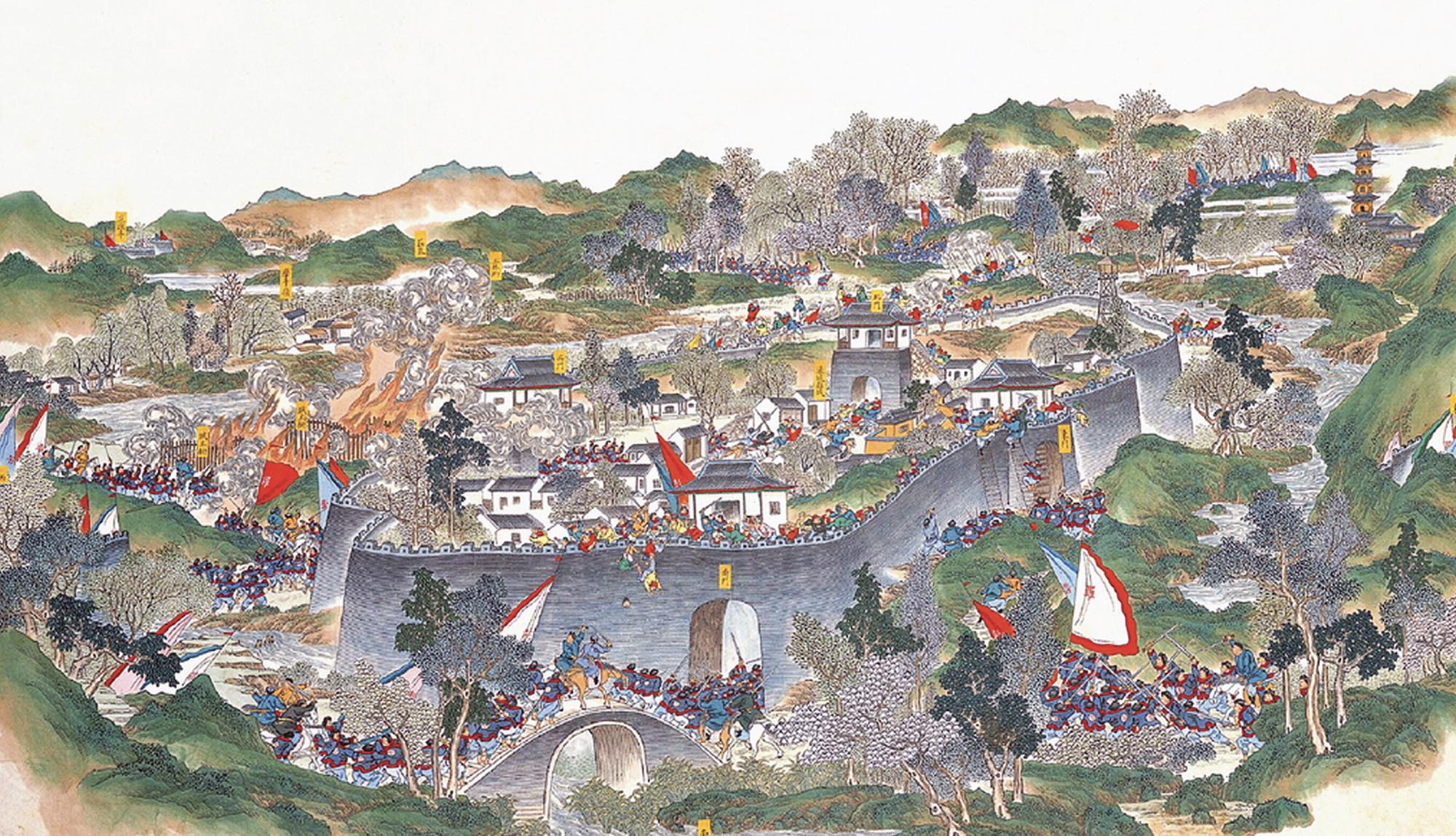

New ideas can spark new hopes and dreams for the future. In the late eighteenth century, revolutionary visions aimed to transform social, economic, and political structures.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- In general, who could participate in the governments of most states around the world before 1750?

- How would you describe the political changes that began in this period?

- The French Revolution promised political participation to many. What did the inhabitants of Saint Louis, a West African port under French rule, think of this revolution? Did they get to participate?

- What does the evidence suggest about the spread of democracy around the world since 1750?

After you watch

Respond to this question: What are some ways that ideas like sovereignty are expressed in our political and legal systems today?

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you read

Preview the questions below, and then skim the article. Be sure to look at the section headings and any images.

While you read

Look for answers to these questions:

- How would you describe the politics and governments around the world at the beginning of the long nineteenth century?

- What new political ideas resulted from the circulation of ideas around the world?

- In which part of the world were the first revolutions during this period?

- What is nationalism, and what role did it play in political revolutions?

After you read

Respond to this question: What were the limitations of the political revolutions that emerged during this period?

Framing Unit 4

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 5 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

Having visual cues for the course frames can help reinforce them with your students. Click to download the WHP Frames Posters.

This video and activity will help us use the frames to evaluate the causes and effects of political and national revolutions during the long nineteenth century.

-

Guiding Questions

-

Before you watch

Preview the questions below, and then review the transcript.

While you watch

Look for answers to these questions:

- What were some of the biggest communities in 1750?

- What other kinds of communities were important in people’s lives around 1750?

- What did almost everyone share in this period, whether they lived in a big empire or a smaller community?

- What were three new ideas about community that emerged during the long nineteenth century?

- Was the rise of the nation-state during this period truly revolutionary?

After you watch

Respond to this question: Why has the nation-state become such a dominant form of community?

Closer: Revolutions

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 6 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

Closers are a great way to informally evaluate student understanding. Read more in the OER Project Assessment Guide.

The age of revolutions turned the world upside down. Or did it?

Essay Review: Analysis and Evidence

To teach this lesson step, refer to page 6 of the Lesson 4.1 Teaching Guide.

A great way to improve your own writing skills is to evaluate writing samples. In this activity, you’ll use your own writing or a sample essay to evaluate the use of analysis and evidence.