Unit 1: The World in 1750

1750 – 1914 CEExplore powerful empires, rich cultures, and global connections while also questioning the stories we tell about them. Look at history through different lenses and uncover what the world looked like in 1750—and why that moment matters for the world you live in today.

Lesson 1.1

History Stories

History is made of stories, but not all stories get told the same way. By questioning perspective and examining evidence, you’ll explore how the past is shaped and why it matters today.

Lesson 1.2

What is World History?

World history is the study of connections linking humanity across our long history. Developing skills like claim testing and scale switching will help you reveal those connections.

Lesson 1.3

History Frames

Looking at the past is like looking through a frame. The frame you choose, whether it’s communities, networks, or production and distribution, can shift what you see and how you understand the bigger picture.

Lesson 1.4

History and Memory

What we remember isn’t always the same as what happened, but together, history and memory shape the stories we share and the communities we build.

The World in 1750

Lesson 1.5

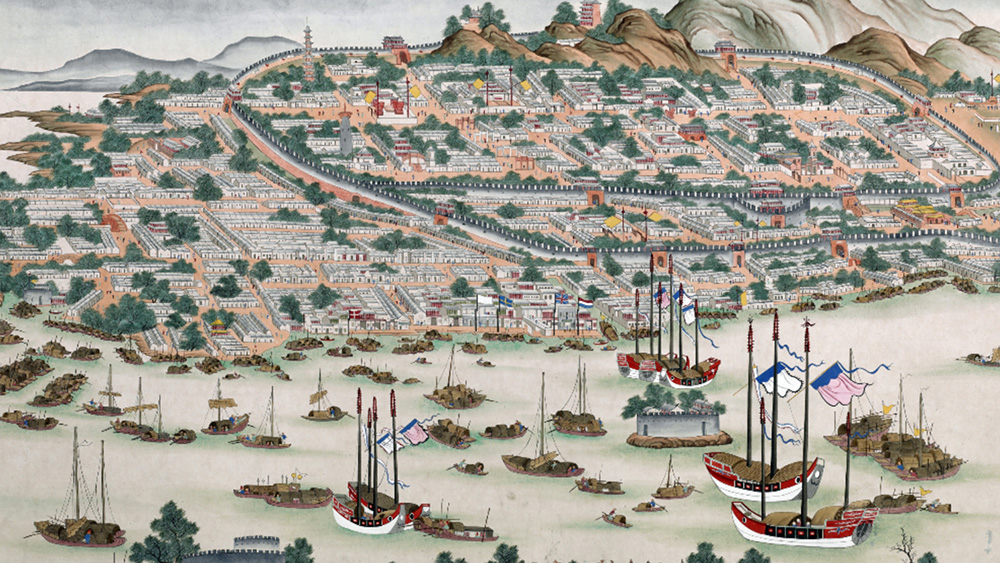

Comparing Europe and China in 1750

In the mid-eighteenth century, China and Western Europe were similar in one important way: they both housed great regional powers. But they were about to diverge in more ways than one. Let’s compare them on the eve of the Industrial Revolution.

Lesson 1.6

Eurasian Land-Based Empires in 1750

Meet the Ottomans, Mughals, and Tokugawa Shogunate, three empires of Eurasia. Who were they? What were their strengths? And what challenges could threaten these mighty forces?

Lesson 1.7

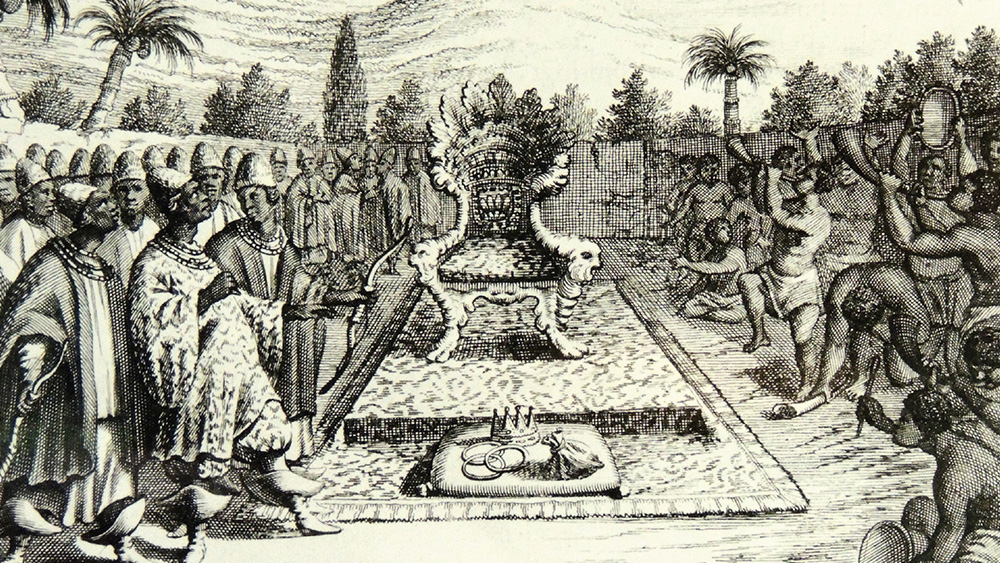

Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific in 1750

Long before Europe dominated the headlines, empires and communities across Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific were shaping global history. Explore the parts of the story we’re often not told.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 1 Vocab

Key Unit 1 vocabulary words and definitions.

Frames Guide

A clear framework helps students examine history through different frames.

Using AI with OER Project

Transform your classroom with AI tools aligned to OER Project materials.

Historical Thinking Skills Guide

Develop the skills needed to analyze history and think like a historian.

Differentiation Guide

Research-backed strategies for differentiation, modification, and adaptation.

Unit 1 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.