Unit 4: Reform Movements

1750 – 1914 CEAs industry expanded, so did inequality. Dig into how work, wages, and rights were redefined—and how people pushed back.

Capital and Labor

Lesson 4.2

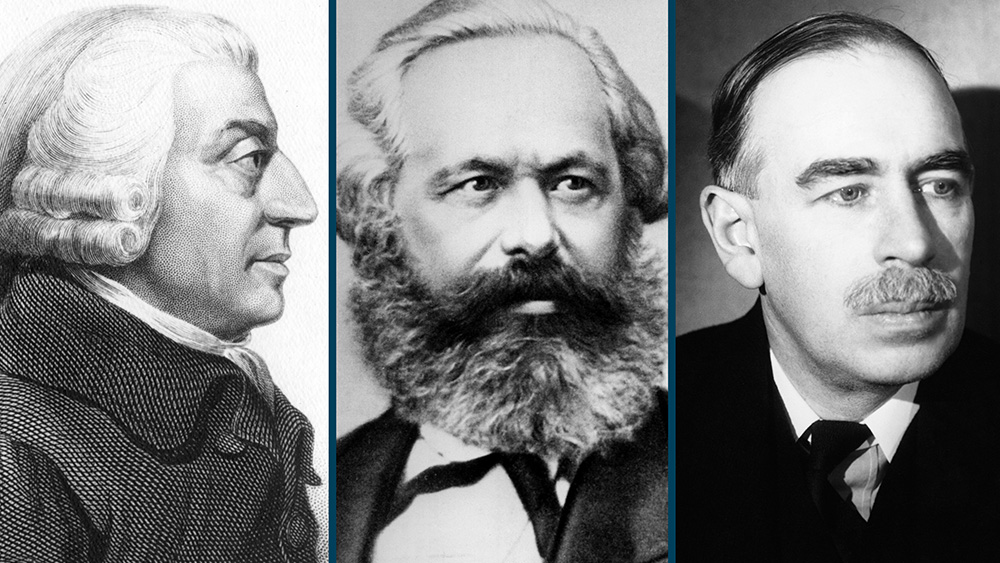

Capitalism and Socialism

Capitalism created new wealth and new struggles. Competing economic ideas offered different answers to the question of who should benefit from labor, and why it matters.

Lesson 4.3

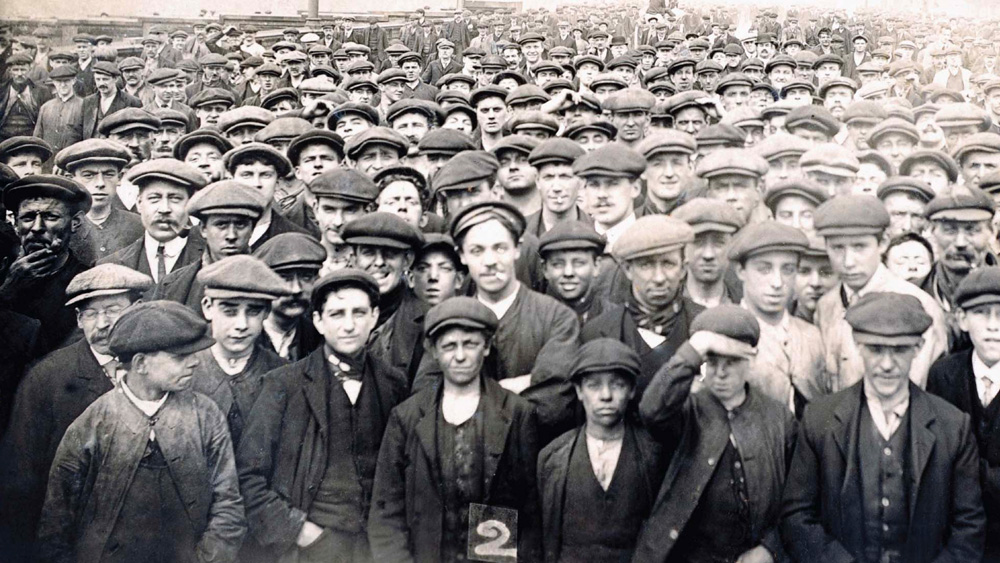

The Division of Labor

Factories didn’t just divide jobs, they divided people. As labor became more specialized, the gap between the workers and those with power became wider and harder to cross.

Reform Movements

Lesson 4.4

Enslavement and Abolition

Even as liberty became a global ideal, slavery remained a global reality. Resistance came from enslaved people, activists, and communities who refused to accept the system. And even with the eventual end of slavery, the fight for equality was far from over.

Lesson 4.5

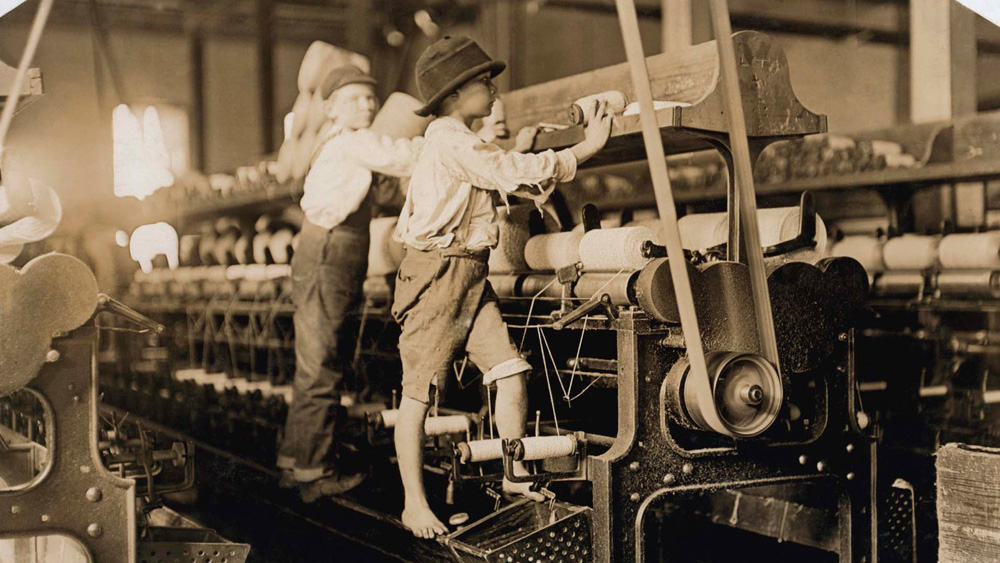

Child Labor

Child labor became part of industrial life. Children worked long hours in dangerous jobs, and their stories helped spark a movement to rethink labor, rights, and the meaning of childhood.

Lesson 4.6

Women’s Rights

Women weren’t just living through the changes of the industrial era—they were pushing change forward. Around the world, communities of women challenged injustice in their personal lives and in the public sphere.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 4 Vocab

Key Unit 4 vocabulary words and definitions.

Reading Guide

Explore the types of texts in OER Project.

Video Guide

Tips for ensuring videos are engaging and instructive.

Writing One-Pager

Quick and easy strategies for incorporating informal writing frequently.

Historical Thinking Skills Guide

Develop the skills needed to analyze history and think like a historian.

Unit 4 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.