3.2 Ways of Knowing – Stars and Elements

-

1 Opener

-

12 Activities

-

2 Videos

-

6 Articles

-

1 Closer

Introduction

In the explosions of dying stars, all of the naturally occurring chemical elements of the Universe were formed. Yet we are still learning new things each day about these elements: their physical properties, potential uses, and hazards associated with them. Early scientists used simple techniques to explore chemistry, but made important realizations that shape science even today.

More about this lesson

- Describe the structure of the periodic table of elements.

- Explain how the formation of stars and the emergence of elements are related to your immediate surroundings (your classroom, your community, the geographic region you live in).

Claim Testing – Intuition

Preparation

Purpose

This activity digs into the “intuition” claim tester and should help you understand how and why intuition can be important, and what to do when you can’t rely on your intuition.

Process

As you come into the room, take about 5 minutes to walk around to the different claims that your teacher has posted and decide if you agree or disagree with each claim, or if you need more information to make a determination about the claim. Once you’ve decided, get some sticky notes from your teacher (one color will be designated for “agree,” one for “disagree,” and a third for “need more information”). On the sticky notes, write your name and the reason you either agree or disagree with each claim and place the notes on the corresponding claims. If your response to a claim is “need more information,” you only need to write your name on the sticky note.

These are the claims you will be evaluating:

- The Earth is flat.

- Humans can live without food or water for a month.

- If an object is dropped, it will fall.

- Humans are the only species capable of love.

- Abraham Lincoln was a championship wrestler.

- A quantum computer can solve any computer science problem in a split second.

- Neanderthals and Denisovans occupied the same caves in Siberia.

Once everyone is done, review the claims one by one with your class and discuss which claim testers you used to make decision about whether or not you believed something.

Finally, answer the following question and turn it in as an exit ticket: Can you decide if a claim is true if you don’t know anything about it? Use one of the examples from today’s lesson as evidence to support your answer.

DQ Notebook

Preparation

Purpose

At the start of the unit, you looked at the driving question for the unit without much to go on. Now that the class has seen a couple of lessons, revisit the driving question. This time, you will cite specific passages and evidence from the content in the unit that provide insights into answering the driving question.

Process

Unit 3 Driving Question: How can looking at the same information from different perspectives pave the way for progress?

Look back over the content covered in the unit as well as any additional information you have come across during the lesson. Write down quotes or evidence that provide new insights into the driving question for unit 3. In your DQ Notebook, describe how this new information has impacted your thinking about the driving question.

Vocab – Word Relay

Preparation

Purpose

In this word relay activity, you’ll practice matching definitions to words. This is a fun, active way to reinforce unit vocabulary, and it will help you become even more familiar with the words you need to know to engage with the content in Unit 3.

Process

You’re going to play a word relay game with the vocab from Unit 3. You’ll get one vocab card and two blank index cards. Here’s how you’ll play the two-part game:

Part 1

- On one of the blank cards, write the definition of the word on your vocab card.

- Once everyone is ready, swap words with another student.

- Write a definition for your new word on your remaining blank card.

Part 2

- Your teacher will split you into teams of four or five. Once you’re in your team, line up single file.

- Now, you’re going to have a relay race to see which team can match the most cards to the most definitions. Your teacher will have set up vocab cards in one part of the room and definitions cards in another.

- The first student in line will pick up a vocab card, then move as quickly as possible to find the definition of that word. Remember, there are two definitions for each word, but you only need one.

- The first team that has a word and definition matched for each team member wins!

Ways of Knowing – Intro to Chemistry

Vocab Terms:

- atom

- chemistry

- composition

- ozone

- property

- spectroscopy

- structure

Summary

Chemistry is used across an amazingly diverse set of disciplines. It helps us to understand the underlying mechanics of many phenomena. As we move on in this course, many of the issues and questions will have chemistry at its source, or at least playing an influential role.

Ways of Knowing – Intro to Chemistry (4:43)

Key Ideas

Purpose

In this short introduction to chemistry, Professor Anne McNeil describes the basic topics and tools in the field of chemistry. This video is designed to provide a view into the field of chemistry and the types of questions a chemist might ask.

Process

Preview

Chemistry is often described as the central science because it is important in the work of scientists in a wide range of other fields. This brief video will provide an introduction to the field of chemistry and the kinds of questions a chemist will explore.

Key Ideas—Factual

Think about the following question as you watch the video:

- What do chemists mean by structure and composition of a compound?

- What is an example of how understanding the structure of a molecule can help us understand its properties?

- What is an example of how chemistry is central to other scientific disciplines?

Disciplines – What Do You Know? What Do You Ask?

Preparation

Purpose

This activity asks you to decide what kinds of questions scholars from different disciplines might ask about an object or a significant event. The goal is to help you solidify your understanding of the different disciplines, but more important, to help you start thinking in an interdisciplinary fashion. Additionally, this activity should help you work on an important skill: the ability to construct researchable questions.

Process

In this activity, you will once again be asked to put together a research team to try to figure out what happened when a huge asteroid hit the Earth (South Africa, to be specific) an estimated 2 billion years ago. This asteroid caused a massive crater in the Earth, now named the Vredefort Crater, or Vredefort Dome. It has an estimated radius of 118 miles, making it the world’s largest known impact structure. It was even declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2005!

You will be given nine discipline cards to help you construct your team: agriculture, astrophysics, anthropology, archaeology, biology, chemistry, cosmology, geology, and conservation science. Take a few minutes to review the cards and ask questions about any of them—you should be familiar enough to be able to assume the perspective of the different disciplines as you work to construct your team.

Once you’re in your group—and before trying to form a team—discuss what you want to know about this asteroid impact. What you choose to ask about the event is directly related to who is doing the asking—so, make sure the topic of study and your disciplines are aligned!

Be prepared to share your team makeup and questions with your class!

Crash Course Chemistry: Periodic Table of Elements

Vocab Terms:

- element

- periodic

- periodicity

- property

- reactive

Summary

Prior to the invention of the periodic table, we knew a lot about individual elements, but we didn’t know how they were connected. The inspiration for this table was the simple card game of solitaire. By taking the information we had about these elements and sorting them in new ways, Mendeleev unlocked some of the most important insights in chemistry.

The Periodic Table: Crash Course Chemistry #4 (11:21)

Key Ideas

Purpose

Chemistry plays an important role in Big History. The elements born in the death of stars are what connect our world today to the stars, their death, and the birth of the Universe. This video provides a brief introduction to how chemists structure the elements and the story behind the periodic table of elements.

Process

Preview

Dmitri Mendeleev did not have a happy childhood. Born in Siberia, his father died when he was 13. To support the family, his mother reopened an abandoned glass-making factory, which burned down a year later. Determined to see Dmitri get an education, his mother took him hundreds of miles on horseback to find a university to accept him. After one rejection, they again went another 400 miles to another university, where he was accepted. His mother then promptly died. This man, who had such a difficult start in life, went on to make some of the most important discoveries in chemistry.

Key Ideas—Factual

Think about the following questions as you watch the video:

- What does it mean that a table is periodic?

- Why are each of these sections important?

- Why does Hank wrap the table around in a cylinder like that?

Thinking Conceptually

Can you think of other examples of situations where you or famous people have looked at a problem in new ways to come up with different answers?

"Pure Metal: Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān"

Vocab Terms:

- alchemy

- alembic

- impurity

- innovators

- sulfuric acid

Preparation

Summary

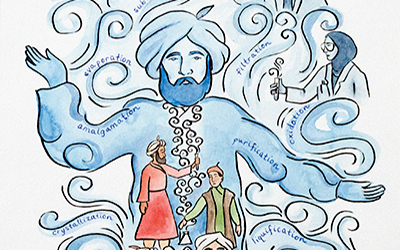

Chemistry is a modern, experimental science dealing with substances—solids, liquids, gases, and more—and how they can change. The modern science of chemistry came together in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but it was based on centuries of theories and experiments. Early chemists were influenced strongly by the work of Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān from eighth- and ninth-century Persia. Whether a single person, or a name later given to a whole school of people working together, Ibn Ḥayyān learned and recorded the characteristics of metals and the tools and methods used to transform them.

Purpose

This article about Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān will help you to learn some of the key elements of chemistry as a science. It will also show you how this science developed over many centuries of experiments and human learning, and will highlight the contribution of Muslim scholars to this process.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, analysis and evidence, and claim testers. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- According to the author, what is the science of chemistry?

- According to the author, did humans do work with chemical changes before the modern science of chemistry emerged?

- Who was Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān, and what contributions did he make?

- What is the debate about the identity of Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān?

- Why was Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān significant, according to the article?

- Look at the art at the top of this article. How would you describe what you see to someone? How does it illustrate some of the issues and arguments in your answers to the first five questions?

Thinking Conceptually

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- The author of this article doesn’t describe Jābir Ibn Ḥayyān as a scientist, but does suggest he used many strategies and techniques that scientists would use. Why do you think the author chose not to call Ibn Ḥayyān a scientist, and why does it matter whom we describe as a scientist?

“Dmitri Mendeleev – Building the Periodic Table of Elements”

Vocab Terms:

- atomic mass

- classify

- element

- organic chemistry

- periodic table

- property

Preparation

Summary

Mendeleev is one of the most famous chemists in history. Building on a few simple insights, he was able to not only create the periodic table of elements but he was able to make predictions about elements that had not even been discovered yet.

Purpose

While unquestionably brilliant, Mendeleev provides us with an important reminder that sometimes our most powerful insights come from simple sources. In thinking about the structure of atoms, Mendeleev looked at the simple game of solitaire to find a way to organize what is today the periodic table of elements.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you do your first close read.

Understanding Content

As you read the article more carefully a second time through, think about the following questions.

- Prior to Mendeleev, how were elements categorized?

- What was the inspiration for the periodic table? What was the connection between that inspiration and what became the periodic table of elements?

- Why is the table called a “periodic” table?

Thinking Conceptually

What are some of the similarities and differences between chemical elements in different parts of the periodic table?

“Marie Curie – Chemistry, Physics, and Radioactivity”

Vocab Terms:

- atom

- element

- half-life

- radiation

- radioactive

- X-ray

Preparation

Summary

Marie Curie is one of the only people in history to win the Nobel Prize twice. Her work led to tremendous insights in the structure and nature of atoms. Yet, her dedication also led directly to her illness and eventual death.

Purpose

The story of Marie Curie is important because of the amazing discoveries she made and the high price she paid to make them.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you do your first close read.

Understanding Content

There are some pretty complex scientific ideas in this article. As you read through it, try to focus on these questions:

- What are x-rays?

- How did Marie Curie know to look for radium?

- What is a “half-life”?

- Why do you think radium glows at night?

Thinking Conceptually

What are some of the key differences between the experience of Marie Curie and other scientists? Did her experience help or hinder her progress?

Scale – Timelines and Periodization

Preparation

Purpose

This activity revisits timelines as analytical tools, with a specific focus on what historians call periodization. You will add two more scientists to the class timeline, which will help you think about how the time period you choose to analyze influences the perspective you might take on a specific historical event or process.

Process

You are going to add two scientists to the timeline you created in Lesson 2.1. You will use the same method you used when looking at our understanding of the Earth, the Solar System, and the Universe.

Do the following:

- Read the articles on Mendeleev and Curie.

- Add to your timeline from Lesson 2.1, and include the following information about each of the scientists:

- Birth and death dates of the scientists

- The major contributions they made

- Who and what influenced their thinking

- Look at your timeline and note how some scientists appear to be clustered on it. Now, do the following:

- Break these clusters of scientists into at least three distinct time periods

- Come up for a name for each time period. The name has to be representative of something about that cluster of people. In other words, each time period should have a theme.

Be prepared to share your method for breaking up and naming your time periods. This process of dividing your timeline into new time periods is called periodization. Periodization is the dividing of history into distinct and identifiable periods. Some examples are geologic periods, such as the Jurassic and Cambrian eras; cultural time periods, such as Gothic and Baroque periods; and geographic categories, such as the dynasties in China.

Historians periodize all the time, because it helps them organize and represent the past in different ways. They might focus on particular topics or interests, or periodize in a way that highlights and supports a specific historical argument. Historians also periodize to de-emphasize some historical information. Imagine if your timeline had only men—or only women. You’d be missing part of the story! As we know, when we zoom in and out on history, or look at the same thing from close up versus far away, our understanding of that thing can change pretty dramatically. Periodization uses different time scales to help us frame the past in different ways.

Look at the timeline again, this time comparing the views of the scientists you just added to those that were already on the timeline. Then, answer the following questions.

- After adding Curie and Mendeleev to the timeline and comparing their views to the previous scientists, explain what the timeline shows when you have them all together. Then, consider how the meaning would change if they were on their own timeline, and explain if one representation is better than the other?

- What are other examples of periodization where we focus on shorter or longer periods of time in history?

- What things should you consider when establishing the period of time you are analyzing?

Analyzing Investigation Writing – Applying BHP Concepts

Preparation

Purpose

In this third activity in the Investigation Writing series, you’ll tackle the fifth row of the BHP Writing Rubric, Applying BHP Concepts. This is yet another way for you to think about how the criteria presented in the rubric can be found in writing. You’ll examine another writing sample from the course, looking for the BHP concepts in the student essay. At the end of this lesson, you should be able to identify the key elements that should be a part of any Investigation essay you write. This is the first step in becoming a more skilled BHP writer.

Practices

Reading, claim testing

You cannot complete this activity’s worksheet without engaging in analytical reading. The practices of reading and writing are bound in many ways, and you should think about those connections whenever possible. The essay you are asked to review discusses claim testing—make sure to review this practice with your class to keep it fresh in your mind.

Process

This is another activity in which you’ll examine a piece of student writing to identify the core elements that should be included in an Investigation essay. This time, you’ll be focusing on the use of BHP concepts. This essay incorporates BHP concepts that you already know a good bit about, even though it’s early in the course—claim testing and the geocentric/heliocentric views of the Universe.

Look at the fifth row of the BHP Writing Rubric – Applying BHP Concepts. When analyzing the student writing sample in relation to this criteria from the rubric, pay attention to whether or not BHP concepts are used, how they are used (that is, are they used accurately and with understanding?), and if the concepts used are connected to arguments made in the paper.

Now, take out the Applying BHP Concepts Worksheet, and read the essay keeping BHP concepts in mind. This essay is in response to the Unit 2 Investigation question, “How and why do individuals change their minds?” After you’ve read the essay once, reread and annotate it, following the directions provided. Once you’re done with the worksheet, review the answers with your class. For your next activity, you’ll be responding to another Investigation question, so be sure to include BHP concepts as part of your Investigation essay.

Organization Warm-Up

Preparation

Carefully read the Investigation prompt you will be responding to. Be sure to have read and analyzed the documents prior to doing this warm-up activity.

Make sure you have drafted the thesis/major claim you intend to use in response to the essay prompt.

Purpose

This warm-up focuses on the Organization row of the BHP Writing Rubric and allows you to refine the way you structure your writing to most effectively support your argument and ideas. You will practice skills to use organization strategies and transitions to support your analysis and establish clear, meaningful connections between ideas. These writing skills are essential not just to essay writing in all your classes, but are applicable to academic, professional, and personal writing at all levels.

Process

In this warm-up activity, you will learn how to organize your essays to help you create a paper that’s easy for your reader to understand. First, you’ll review the Organization row of the rubric, and then, you’ll work through a three-step process that will help you think about how you’ll organize your essay.

First, take out the BHP Writing Rubric and review the Organization row with your class. Discuss what you think organization is in this context and why it’s important to consider when writing essays. Remember, all arguments should have three components that make up the basic organization: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Within those components, writers make choices about the best way to order and present their ideas. Some writers use categories to structure their paragraphs (for example, economic, social, and so on). Others lay out their points in order of importance or move from most general to most specific. When we discuss organization in the context of the rubric, we’re really talking about the existence and effectiveness of the introduction and conclusion, along with the order in which ideas are presented within the body.

Additionally, a well-organized essay provides the reader with a road map, which should help them follow the writer’s argument more easily. So, how do you organize a paper? Well, there’s a tool for that!

Take out the Organization Prewriting Tool and work through it according to your teacher’s instructions.

First, add the thesis/major claim to the top of the tool. Then, for Step 1, come up with three claims—or reasons—that support the thesis/major claim statement you just wrote. Then, for Step 2, use transition words to help you write your introduction and organize your body paragraphs.

Now you’re ready for Step 3, your conclusion. First, choose a transition word that will help you start your concluding paragraph. Then, summarize your supporting claims and their significance, describe why your argument is important, and then restate your thesis/major claim. The work you complete in Step 3 will help you write your concluding paragraph later.

Once you’ve completed the steps, it’s time to write!

Investigation 3

Preparation

Investigation 3 Prompt: How can looking at the same information from different perspectives pave the way for progress?

Purpose

This Investigation continues to explore the development of collective learning, a central theme in the Big History course, by asking you to consider how a new point of view can pave the way for new discoveries and create progress. This Investigation will help you further develop your claim-testing practices and ability to use evidence to support your ideas in document-based questions you will encounter on standardized exams. Additionally, this assessment helps you refine your ability to determine relationships between ideas.

Process

Day 1

In this activity, you’re going to respond to a question using texts to support your thinking in the form of an Investigation. In this course, Investigations give you a question along with several source documents, and you will use the information in those documents (and perhaps additional knowledge) to respond to the question. Your response will be written in essay format and will be five- to six-paragraphs long. This Investigation asks you to respond to the question, How can looking at the same information from different perspectives pave the way for progress?

First, your teacher will ask you to write down your conjectures—or your best guesses made without lots of evidence—about why and how new points of view or ways of seeing things can pave the way for discovery and progress. Think about examples from your own life or from history when a different point of view opened up new possibilities.

You’ll have about 5 to 10 minutes to make notes and think about what causes individuals to change their minds.

With your class or in small groups, share your list of ideas about how looking at the same information from different perspectives can pave the way for progress. Next, your teacher will either hand out or have you download the Investigation 3 Document Library. As you review each document, you’ll use the graphic organizer to record the major claims from each source and to document the evidence that supports those claims.

Day 2

Now it’s time to write! You’ll develop a five- to six-paragraph essay arguing how and why looking at the same information from different perspectives can pave the way for progress, using evidence from the case study of new ideas in chemistry. Remember to use information from the Investigation 3 Document Library along with BHP concepts and other information you’ve learned in this unit as evidence to support your argument or opposing point of view. It’s also important that you cite the sources you use as evidence in your essay.

Investigation Writing Samples

Preparation

Purpose

In order to improve your writing skills, it is important to read examples—both good and bad—written by other people. Reviewing writing samples will help you develop and practice your own skills in order to better understand what makes for a strong essay.

Process

Your teacher will provide sample essays for this unit’s Investigation prompt and provide instructions for how you will use them to refine your writing skills. Whether you’re working with a high-level example or improving on a not-so-great essay, we recommend having the BHP Writing Rubric on hand to help better understand how you can improve your own writing. As you work to identify and improve upon aspects of a sample essay, you’ll also be developing your own historical writing skills!

Organization Revision

Preparation

Have your graded essay ready to use for annotation and revision purposes.

Purpose

The purpose of this activity is for you to become familiar with a revision strategy for improving an essay’s organization. A good way to improve writing skills is to analyze writing samples as an editor, using a peer draft or your own essay that was graded by your teacher or peers. By thinking carefully about the criteria in the BHP Writing Rubric and evaluating a piece of writing against it, you will develop a better understanding of what makes an exemplary piece of writing. This, in turn, will improve your writing.

Process

In this activity, you’ll first review the Organization row of the BHP Writing Rubric with your class if you haven’t already done so. Then, you’ll review the Organization Revision Tool and learn how to use it to improve upon the essay’s overall clarity and organization. Finally, you’ll use the Organization Revision Tool to review and revise an essay.

If needed, start by reviewing the Organization row of the BHP Writing Rubric with your class. Discuss why it’s important to think carefully about how an essay is structured. Also, keep in mind that a well-organized essay always has an intro, a body, and a conclusion.

Next, take out the Organization Revision Tool and walk through it with your class. First, note the directions at the top, which ask you to review the feedback from an essay. This is a helpful step because it gives you a general sense of how the essay fared in terms of overall organization and clarity and where improvement is needed.

Now, it’s time to go through each item on the checklist to make sure all criteria related to organization were included in the essay. Work through the list with your class and be sure to ask questions if you aren’t clear about what an item is asking for. Remember, only check the boxes if the criteria are met. If any criteria from the checklist were not met, leave those boxes blank. The final step is to revise the essay based on all the blank checkboxes. Use the unchecked boxes as guidance for what can be done to improve the organization of the essay. You can also use the Organization Prewriting Tool to help structure revisions.

Once you feel like you have mastered how the Organization Revision Tool works, your teacher may have you work on another essay to practice your skills.