Unit 1: Origins of History

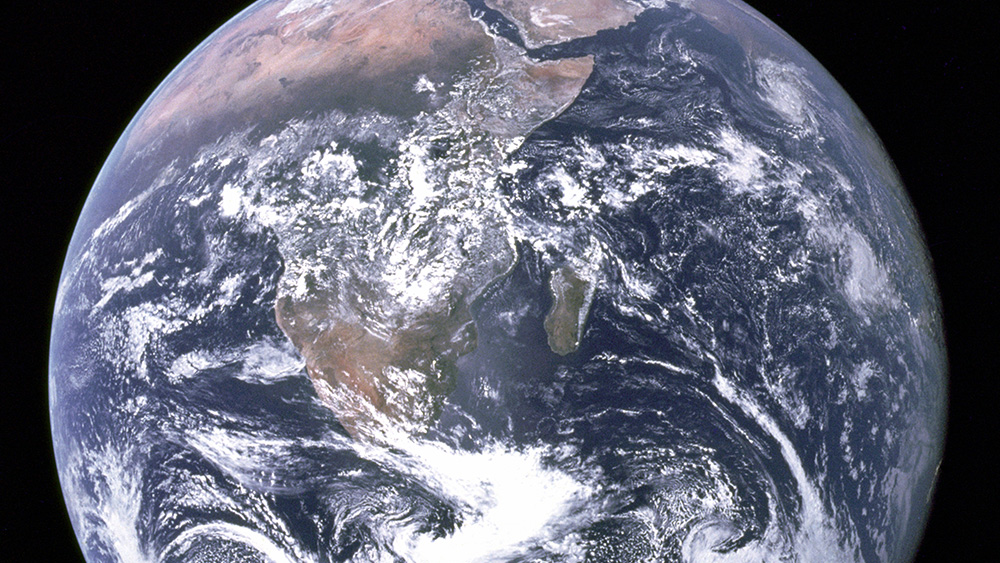

Everything has a history. This course begins with the history of you and expands to the history of the entire world.

No matter how big or how small, everything has a past and a history that can be written. This course begins with the history of you and expands to the history of the entire world.

Lesson 1.1

History Stories

We can’t study the past without thinking about who’s telling the story, and why. By considering multiple perspectives on events, historians can come closer to objective truths.

Lesson 1.2

What Is World History?

World history is the study of connections linking humanity across our long history. Developing skills like claim testing and scale switching will help you reveal those connections.

Lesson 1.3

History Frames

World history is too big to see everything at once. That’s why we use different frames of reference to help focus our attention on smaller details in the bigger picture.

Lesson 1.4

History and Memory

Each of us has a history, and each of us has memories. What’s the difference between history and memory?

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Frames Guide

A clear framework helps students examine history through different frames.

Using AI with OER Project

Transform your classroom with AI tools aligned to OER Project materials.

Historical Thinking Skills Guide

Develop the skills needed to analyze history and think like a historian.

Differentiation Guide

Research-backed strategies for differentiation, modification, and adaptation.