Unit 6: World War I

1914 – 1919 CEThis wasn’t just a European war. It was a global turning point. Uncover how one spark pushed the world into a conflict and how its impact reached far beyond the battlefield.

The First Total War

Lesson 6.2

Causes of the First World War

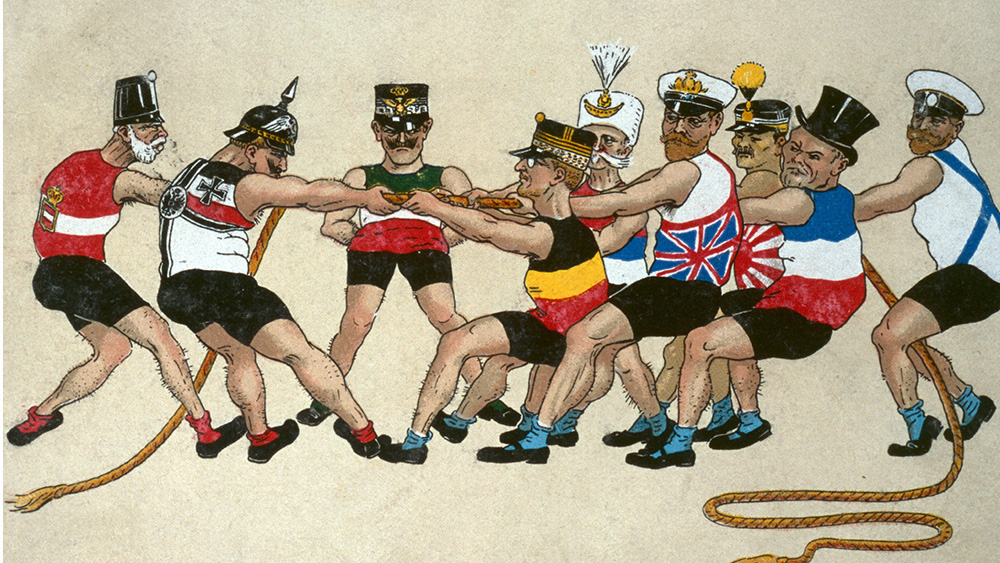

Military forces grew, alliances solidified, and tensions rose across continents. When war finally came, it was no accident; it was the result of systems pushed to the breaking point.

Lesson 6.3

Total War

World War I was more than a battlefield—it was a global experience. It blurred the line between home and front, and changed what war looked and felt like.

Experiences and Outcomes

Lesson 6.4

Living in Total War

What did it mean to be part of the lost generation? Firsthand perspectives from the war reveal the fear, courage, and resistance that shaped the lives touched by total war.

Lesson 6.5

The World Remade

World War I left behind more than wreckage. From fragile peace talks to sweeping revolutions, it pushed people to imagine new ways to organize on global, national, and local scales.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 6 Vocab

Key Unit 6 vocabulary words and definitions.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Reading Overview

Reading strategies to help students dig into a variety of texts.

OER Teaching Sensitive Topics in Social Studies Guide

Support for having discussions that are difficult, but meaningful.

Historical Thinking Skills Guide

Develop the skills needed to analyze history and think like a historian.

Unit 6 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.