6.3 How Did the First Humans Live?

-

1 Opener

-

3 Videos

-

4 Articles

-

8 Activities

-

1 Closer

Introduction

Waking to the sunrise over miles of flatlands, walking fields in search of water and berries, risking death and injury while hunting animals, and relaxing with friends and family under a setting sun were all part of early human life. In the previous lesson students learned about collective learning and how important symbolic language is to this process of sharing, preserving, and passing down information. Collective learning became increasingly important to early humans as they continued to evolve, which strongly influenced how early humans lived. This lesson will focus upon how our early ancestors lived and students will attempt to decide whether life as a forager (hunter-gatherer) might have been better than life as we know it today.

More about this lesson

- Describe how early humans lived.

DQ Notebook

Preparation

Purpose

In Lesson 6.1, you took a stab at answering the Unit 6 driving question. Now that you’ve accumulated more knowledge on the subject, you’ll revisit the question: What makes humans different from other species? This time, cite specific passages and evidence from the unit that provide insights into answering the driving question.

Process

Driving question: What makes humans different from other species?

Look back over the content covered in the unit as well as any additional information you have come across during the lesson. Write down quotes or evidence that provide new insights into the driving question for Unit 6. Use the third column of the DQ Notebook Worksheet – Unit 6 to describe and reflect on how this new information has impacted your initial thinking about the driving question.

How Did the First Humans Live?

Vocab Terms:

- anthropology

- archaeology

- foraging

- migration

- Paleolithic

- tool

Summary

Foraging communities would have been very closely connected to each other and would have shared information about their environment. This sharing of information led to increased knowledge of how to extract the most from the land, which eventually led to a whole new system of acquiring food.

How Did the First Humans Live? (10:52)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video gives you an idea of what life might have been like as a nomadic forager so you can understand and answer the question that drives this lesson: How did the first humans live? By studying the diet and migratory patterns of early humans, you’ll be able to see how collective learning played an instrumental part in allowing humans to dominate the biosphere.

Process

Preview

Our Homo sapiens ancestors lived as nomadic foragers. Over time they developed and shared skills and techniques to better survive in their environment. The nomadic lifestyle of early humans led people to settle in many places around the globe.

Key Ideas – Factual

As you watch this video, use these questions to help you check for understanding.

- What is foraging and how was it used by early humans?

- Why did foraging techniques change from community to community?

- What was life like for a nomadic forager and how was collective learning used?

- During this era, how did humans migrate? What about their belongings?

- Why did the eventual settlement of the entire world and global climate change set humans on an entirely different trajectory from the one they have been on?

Thinking Conceptually

Why do you think early humans began to settle down? What would have been some advantages and disadvantages associated with the end of foraging?

“Foraging”

Vocab Terms:

- forager

- foraging

- gather

- hominin

- traditional

Preparation

Summary

Until the dawn of agriculture, humans had to rely on hunting and gathering to feed themselves. This required groups of people to remain relatively small in number and to move frequently. As humans development increasingly sophisticated tools, there were still limits on the amount of food they were able to find. However, with increased migration and the ice age receding, important changes lay ahead.

Purpose

This article goes into a bit more depth about the life of a nomadic forager and gives a slightly different explanation of foraging than in the video. After reading this article and answering the questions that follow, you’ll better understand the importance of foraging.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Over generations, early humans become increasingly sophisticated about obtaining food for themselves and their families. They learned what was good to eat and where to find it. They developed better tools to help them hunt and prepare the food they found. They even learned to control fire, which enabled them to cook their food.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions about collective learning:

- What are the key differences between the way humans and animals forage for food?

- As early humans developed new and better sources of food, what was the impact on human development?

- How are these developments examples of collective learning?

Thinking Conceptually

How do you think foragers eventually began to settle down and develop new ways to procure food?

Claim Testing – Early Humans

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, you’ll continue to build on your claim-testing skills by crafting supporting and refuting statements for a set of claims. As you evaluate the claims, you’ll also analyze the quality of the statements put forth by your classmates. This will help you gain experience in using evidence to support your own claims as well as devising ways to refute statements that might argue against your claims. In addition, these skills will help you develop your writing and critical thinking skills.

Process

In this claim-testing activity, you are given four claims about early humans. You are asked to work with these claims in three different ways:

- Find supporting statements for those claims.

- Evaluate the strength of the supporting statements provided for those claims.

- Provide statements that refute (argue against) the claims.

Get into small table groups. Each group should have a complete set of Claim Cards in the middle of their table. Listen for your teacher’s directions for when to start.

Round 1

- Grab one Claim Card from the center of the table.

- On the card, write down a statement that supports the claim. You can use prior knowledge or course materials for this.

- Pass your Claim Card to the person to your right.

- Write down a statement that supports the claim on the card that you now have. It can’t be the same as any of the supports already written on the card.

- Repeat the process until each group member has written a supporting statement on each card.

- Put the Claim Cards back in the center of the table.

Round 2

- Grab one Claim Card from the pile and stand up.

- Find at least three other students who have the same claim as you and get into a group with them (if there are more than six people in your group, let your teacher know).

- Look at all the supporting statements that were written for your claim. Decide which supporting statements are strongest (that is, they best support the claim).

- Write the strongest supporting statements on the whiteboard so everyone can see them.

Round 3

- With the same group you were in for Round 2, consider any historical exceptions to your claim. What can you offer to refute the claim?

- Add at least one refuting statement, what we often refer to as a counterclaim, on the board so everyone can see it.

- Present both your strongest supporting statements and the exception to the claim to the class—be sure to explain your reasoning for choosing your supporting statements and refutations.

Once you are done, your teacher may ask you to write a one- to two-paragraph mini-essay using one of the claims as a thesis statement. Then, you’ll use a few of the best supporting statements as evidence to support your thesis claim. Be sure to acknowledge the counterclaim or refuting statements in your mini-essay. For example:

- You might begin your mini-essay by stating the claim.

- Then, you should use the supporting statements you’ve identified as being the strongest to explain why this claim (thesis) is correct.

- Finally, you’ll acknowledge the counterclaim by including the strongest refuting statement you identified in the activity.

This activity will help you learn the best way to use supporting statements as evidence for a thesis statement, and how to acknowledge counterclaims in essay writing.

From Foraging to Food Shopping

Vocab Terms:

- choice

- diet

- environment

- hunter-gatherer

Summary

Similarities between modern humans and our ancient ancestors go beyond physical appearance and genetics. While we may no longer stalk our food or gather wild nuts and berries in the forest, we do choose our food in some similar ways. There is a definite connection between our modern diet and food choices and those of foragers.

From Foraging to Food Shopping (4:11)

Key Ideas

Purpose

How do we choose what types of food to buy at the grocery store? How might foragers have chosen the types of food they wanted to hunt and gather? Professor Waguespack links these two questions and provides you with a different way to think about how and why we select our food.

Process

Preview

Every day, we make decisions about what to eat and how we’re going to eat it. However, did you know the decisions we make about food today extend far back into human prehistory? Even though fatty burgers and tasty gummies are a relatively new addition to the human diet, there’s a good chance our foraging ancestors would have loved them too.

Key Ideas – Factual

Think about the following questions as you watch the video:

- What kinds of food would hunter-gatherers prefer and why?

- Why would hunter-gatherers go to extra lengths to get foods like bone marrow, nuts, and honey?

- Why did extinctions often occur after humans settled in a particular area?

Thinking Conceptually

Do you think modern humans will one day have to return to a foraging lifestyle? How do you think you’d survive?

Hunter Gatherer Menu

Preparation

Purpose

You will gain a better understanding of how our foraging ancestors lived by thinking about the things that hunter-gatherers ate, and how they procured those foods. Not only does this provide more detail about the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, it should also help you understand some of the difficulties that hunter-gatherers faced, and some of the factors that may have led to the transition to agriculture.

Process

Begin this activity by choosing a name and location for your imaginary restaurant, along with a date to correspond to when people would have been foraging in this location. Then research what a typical forager might have hunted and gathered in your geographical region in order to put together your menu. You must include information on the tools used to forage that particular food item as well as information about where the food item was located.

Crash Course Big History: Why Human Ancestry Matters

Vocab Terms:

- foraging

- gene

- genetics

- migration

- pseudoscience

- tribal

Summary

Given how advanced we are now, the 250,000 years of human evolution that brought us here was a relatively short time. But considering how genetically similar all humans are around the world, it is impossible to deny that we have often focused on our differences in wars great and small. Science has offered some explanations of how we got this way, however science has also been abused to confirm biases and marginalize others.

Crash Course Big History: Why Human Ancestry Matters (10:26)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video lays out the important numbers of human evolution: when things happened and how many of our species were around at various times. Some distressing aspects of humanity—such as our throw-back instinct for dominance, as well as the danger of pseudoscience—will help you see how fact-based, critical thinking can bring us toward a more peaceful world.

Process

Preview

Humans emerged about a quarter of a million years ago. A devastating event that reduced our numbers, a subsequent population boom during an ice age, and millennia of intercontinental migration all serve as evidence that humanity began in Africa. While we celebrate our differences in a world that sometimes pits us against each other, genetics indicate that as a global species, we are vastly similar.

Key Ideas – Factual

Think about the following questions as you watch the video:

- How and why did the human population change over the last 200,000 years?

- When some humans left Africa 64,000 years ago, how and where did they spread across the globe for the next 50,000 years—at least in theory?

- What is the variable that determines skin color, and how genetically different does it make people?

- Why do humans seem prone to fighting each other and emphasizing our differences, and how might modern humans avoid this?

- How is evolutionary “pseudoscience” dangerous?

Thinking Conceptually

What are some of the forms of pseudoscience that have been practiced in the past? What are some pseudosciences that are practiced today?

Human Migration Patterns

Preparation

Read “The Great Human Migration” on the Smithsonian Magazine website

Purpose

In this activity, you will use a variety of skills to complete the tasks, including close reading and comprehension abilities, researching, and mapping. The reading part of this activity requires you to read for both information (clues) and for understanding, in order to complete the mapping section. Creating the map will give you a visual representation of when and where early humans moved after leaving Africa.

Process

First, read the Smithsonian article, “The Great Human Migration.” As you read, note or highlight every piece of information or clue given about human migration out of Africa. Your teacher will then assign you to a small group to begin mapping the migration patterns of early humans, using the Human Migrations Patterns Worksheet. Begin by labeling the following parts of the map: Africa, Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, the Middle East, Israel, Turkey, the Arabian Peninsula, Croatia, India, Asia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Australia, North America, South America, the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

Compare the clues you discovered in the article with those found by your group members to decide which pieces of information are important to the story of human migration. Using the symbols provided in the map legend, draw the course of human migration as told in the article. You should draw migration routes, water crossings, mountains, and evidence of human habitation including Homo sapiens and Neanderthal areas of settlement. Lastly, in order to put all of this into a chronological time frame, label the migration routes with the approximate date ranges for when humans moved into these areas.

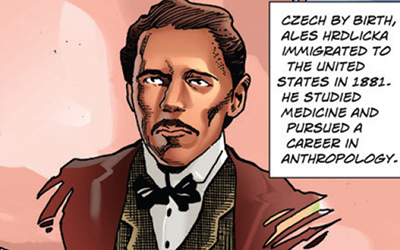

Ales Hrdlicka – Graphic Biography

Preparation

Summary

Ales Hrdlicka (1869-1943) was a Czech-born anthropologist who dedicated his career to professionalizing his field. While he was one of the first scientists to claim that humans came to the Americas from Asia across the Bering Strait, he also stubbornly refused to accept mounting evidence that his timeline of human history in the Americans was wrong. Hrdlicka steadfastly rejected opposing viewpoints. This delayed a revolution in the understanding of the human past in the Western Hemisphere.

Purpose

How did our early ancestors evolve? How did scientists and scholars piece together information to understand the story of human evolution and the great migrations our species undertook many thousands of years ago? This biography of Ales Hrdlicka helps you answer these questions and shows the importance of using evidence from multiple perspectives to build upon and question our collective learning.

Process

Read 1: Observe

As you read this graphic biography for the first time, review the Read 1: Observe section of your Three Close Reads for Graphic Bios Tool. Be sure to record one question in the thought bubble on the top-right. You don’t need to write anything else down. However, if you’d like to record your observations, feel free to do so on scrap paper.

Read 2: Understand

On the tool, summarize the main idea of the comic and provide two pieces of evidence that helped you understand the creator’s main idea. You can do this only in writing or you can get creative with some art. Some of the evidence you find may come in the form of text (words). But other evidence will come in the form of art (images). You should read the text looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the main idea, and key supporting details. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What was an important contribution that Ales Hrdlicka made to the field of anthropology?

- What did Hrdlicka believe to be the timeline of human history in the Americas? According to his writing, why did he think this?

- In 1926, archeologists in Folsom, New Mexico discovered evidence that undermined Hrdlicka’s timeline. What did they discover, and what was Hrdlicka’s response?

- In the center of the page, a large image of Hrdlicka is shown blocking a group of early humans moving from Asia towards the Americas. How does the artist use these images to contribute to your understanding of Hrdlicka?

Read 3: Connect

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in this unit of the course. On the bottom of the tool, record what you learned about this person’s life and how it relates to what you’re learning.

- What evidence does Ales Hrdlicka’s story provide about the way collective learning is built overtime?

- How does it support, extend, or challenge what you have already learned about human evolution?

To Be Continued…

On the second page of the tool, your teacher might ask you to extend the graphic biography to a second page. This is where you can draw and write what you think might come next. Here, you can become a co-creator of this graphic biography!

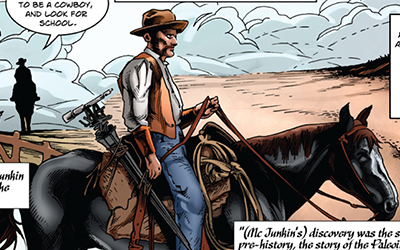

George McJunkin – Graphic Biography

Preparation

Summary

George McJunkin (1852-1922) was an African American cowboy born into slavery. When he discovered old bones in a dry riverbed, he knew they were not ordinary cow bones. He collected samples and invited experts to come visit the site, but none did until after his death. What they found when they examined the bones McJunkin had discovered transformed archeology and the understanding of human history in the Americas. McJunkin did not receive any credit for his role in discovering the fossils until decades after the original discovery.

Purpose

In this unit, we explore how our ancestors evolved and how scientists and scholars have pieced together an understanding of our human history. This biography of George McJunkin provides evidence from one individual’s life to help you understand the importance of collective learning. It asks you to think deeper about the question, “Who gets credit for discoveries that unfold over the course of centuries?”

Process

Read 1: Observe

As you read this graphic biography for the first time, review the Read 1: Observe section of your Three Close Reads for Graphic Bios Tool. Be sure to record one question in the thought bubble on the top-right. You don’t need to write anything else down. However, if you’d like to record your observations, feel free to do so on scrap paper.

Read 2: Understand

On the tool, summarize the main idea of the comic and provide two pieces of evidence that helped you understand the creator’s main idea. You can do this only in writing or you can get creative with some art. Some of the evidence you find may come in the form of text (words). But other evidence will come in the form of art (images). You should read the text looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the main idea, and key supporting details. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- In the early 20th century, what was the prevailing belief among archeologists regarding human history in the Americas? How was that different from beliefs held by Indigenous Americans?

- Why was McJunkin’s discovery at the Folsom site significant?

- The professional archeologists who first came to the Folsom site years after McJunkin’s death never gave him credit for his role in the discovery. How then, decades later, did his contribution begin to be acknowledged?

- Throughout the graphic biography, McJunkin’s face is covered in shadow. Why do you think the artist chose to represent his image in that way?

- There are two quotes from George Agogini in this biography. Do the two quotes agree with each other? Why do you think these two quotes are significant?

Read 3: Connect

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in this unit of the course. On the bottom of the tool, record what you learned about this person’s life and how it relates to what you’re learning.

- How does this biography of George McJunkin support, extend, or challenge what you have learned about collective learning and the way stories and knowledge are passed through generations?

To Be Continued…

On the second page of the tool, your teacher might ask you to extend the graphic biography to a second page. This is where you can draw and write what you think might come next. Here, you can become a co-creator of this graphic biography!

Little Big History – Choosing Your Focus

Preparation

Purpose

For this activity, you and your LBH group members will make a final decision about the object that you will study and research for your Big History project. This is an important step in the process and will keep your group focused on the task and working toward completing your Little Big Histories.

Process

Get into your LBH groups for this final activity to help you pick your LBH object or commodity. Do you remember the Historos Cave activity from Lesson 6.1? If not, you might want to take a quick look back at that lesson because this activity will be kind of like that one. Just as in the Historos Cave activity, your teacher will assign or have you pick one scientific role:

- anthropologist

- archaeologist

- geologist

- paleontologist

Each of you will work independently to write down one or two questions about each of the two objects or commodities that you chose in Part 1 (and have maybe even been thinking about!). The questions should be ones that you, in your role as a particular kind of scientist, would ask about the object.

After you’ve had a chance to think about and write down your questions, discuss them with the other members of your group. You may find that some objects elicited more interesting questions than others, or some objects were incredibly difficult to ask about. Based on the questions all of you were able to ask and the lines of inquiry you might follow for the project, pick your focus for the Little Big History project. Be sure prepared to share your decision—what you picked and why—with the class.

Revising Investigation Writing – Applying BHP Concepts

Preparation

Purpose

By now, you should be very familiar with these Investigation writing activities. In case you forgot, the point of doing these is to have you work on particular elements of writing so that you improve throughout the year. BHP research has shown that students dramatically improve their writing in the first half of the course, but then their progress tends to stay roughly the same in the second half of the course. These activities will help you continue to become a better writer throughout the course, not just during the first half.

Process

Take out the Revising Investigation Writing – Applying BHP Concepts Worksheet. You are about to do another activity in which you will read some student writing and then analyze and revise it to make sure that the writer has applied BHP concepts in the best ways possible.

With your class, review the elements in the BHP Writing Rubric for Applying BHP Concepts. To be considered “Advanced” at applying BHP concepts effectively, you should:

- Connect at least two BHP concepts to the argument and/or evidence.

- Avoid misconceptions of the concepts.

- Make no errors of fact when using BHP concepts.

- Draw on knowledge within the Investigation or unit and perhaps include knowledge beyond or outside the Investigation or unit.

- Demonstrate a clear understanding of the topic and the concepts.

Now that you’ve reviewed the criteria for Applying BHP Concepts, read the sample essay on the worksheet and follow the directions. You’ll be asked to first highlight the major claim or thesis in the article. Then, underline anywhere BHP concepts were applied. After that, pick two sentences/areas where you believe the writing could be improved in relation to applying BHP concepts, and then revise that writing. Finally, provide the writer with two general comments/suggestions about how the writer could improve upon the essay more generally. You might focus on other areas of the BHP Writing Rubric that you’ve examined in detail in other lessons, or other areas of writing that you’ve been working on as a class.

After you’re done, discuss what you did with your class. Remember, Investigation 6 is up next, and your teacher may use it as a midterm assessment (it’s definitely used by BHP for research so we can keep figuring out how to improve student writing). Of course, you should take all Investigation writing seriously. You should think hard about what you’ve learned about constructing arguments, using evidence to support those arguments, and applying BHP concepts, and make sure to apply what you know in the Unit 6 Investigation essay.

Investigation 6

Preparation

Investigation 6 Prompt: How does language make humans different?

Purpose

This Investigation will help you explore the role that symbolic language plays in the development of collective learning. Comparing the way that human communication is similar to and different from that of other species will help you consider the effect language has had on human history. Additionally, this assessment helps prepare you to make evidence-supported claims for document-based questions you will encounter on standardized exams.

Process

Day 1

In this activity, you’re going to respond to a question using texts to support your thinking in the form of an Investigation. In this course, Investigations give you a question along with several source documents, and you will use the information in those documents (and perhaps additional knowledge) to respond to the question. Your responses will be written in essay format, and will be five- or six-paragraphs long. This Investigation asks you to respond to question, How and why do individuals change their minds?

First, your teacher will ask you to write down your conjectures—or your best guesses made without lots of evidence—about the following questions: When and why do you think people should change their minds, particularly about things that most other people believe? What do you think made Copernicus and Galileo change their minds about the Earth being the center of the Universe?

You’ll have about 5 to 10 minutes to make notes and think about what causes individuals to change their minds.

With your class or in small groups, share your list of ideas about why people change their minds. Next, your teacher will either hand out or have you download the Investigation 2 Document Library. As you review each document, you’ll use the graphic organizer to record the major claims about the structure of the Universe in the texts and to document which claim testers support those claims.

Day 2

Now it’s time to write! You’ll develop a five- to six-paragraph essay arguing how and why individuals change their minds, using evidence from the case study of Copernicus and Galileo to support your argument. Remember to use information from the Investigation 2 Document Library along with BHP concepts and other information you’ve learned in this unit as evidence to support your argument or opposing point of view. It’s also important that you cite the sources you use as evidence in your essay.

Investigation Writing Samples

Preparation

Purpose

In order to improve your writing skills, it is important to read examples—both good and bad—written by other people. Reviewing writing samples will help you develop and practice your own skills in order to better understand what makes for a strong essay.

Process

Your teacher will provide sample essays for this unit’s Investigation prompt and provide instructions for how you will use them to refine your writing skills. Whether you’re working with a high-level example or improving on a not-so-great essay, we recommend having the BHP Writing Rubric on hand to help better understand how you can improve your own writing. As you work to identify and improve upon aspects of a sample essay, you’ll also be developing your own historical writing skills!