8.3 Commerce & Collective Learning

-

1 Opener

-

10 Activities

-

2 Videos

-

10 Articles

-

2 Closer

Introduction

Evading bandits through mountain passes, leading a caravan of yaks carrying silk and goods, sailing the trade winds off the Indian coastline – these are a few things you might have done as a trader in the age of agrarian civilizations. Systems of exchange and trade between large agrarian civilizations facilitated the transfer of goods from one civilization to the next, but they also helped share the world’s religions, ideas, innovations, diseases, and people. While each world zone had its own trade routes, none were as vast and intense as the Silk Road. This large system of exchange and trade, initially designed for commerce, dispersed goods and ideas throughout Afro-Eurasia, and paved the way for a substantial increase in both commerce and collective learning.

More about this lesson

- Investigate the implications of interconnected societies and regions by looking at how commerce has spread.

- Explain how new networks of exchange accelerated collective learning and innovation.

Quick Poll - Has the Scientific Revolution Ended?

Preparation

Purpose

In this lesson, you’ll start thinking about how interconnectedness influenced the spread of ideas, and how this brought about the Age of Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. These events occurred hundreds of years ago, but the question of whether or not the Scientific Revolution has ended is up for debate. This quick poll asks you for your initial thoughts as an entrée into this topic.

Process

This activity should take no more than 5 minutes. Your teacher is going to ask you a few yes/no questions. If your answer to any of the questions is yes, raise your hand after being asked that question. Also, be sure to record your answers on your worksheet so you can refer to your initial thinking on these questions later in the lesson.

- Has the Scientific Revolution ended?

- Did the Scientific Revolution start at the same time as global interconnectedness?

- Will the Scientific Revolution ever end?

- What disciplines (for example, Big History, history, technology) count as science?

Be prepared to give a reason why you answered one way or the other, the evidence you would use to support your answer, and what claim testers your evidence matches up with.

DQ Notebook

Preparation

Purpose

At the start of this unit, you looked at the Unit 8 driving question without much to go on. Now that you’ve seen a couple of lessons, you'll revisit the question: What are the positive and negative impacts of interconnection? This time, cite specific passages and evidence from the content in the unit that provide insights into answering the driving question.

Process

Unit 8 Driving Question: What are the positive and negative impacts of interconnection?

Look back over the content covered in the unit as well as any additional information you’ve come across during the lesson. Write down quotes or evidence that provide new insights into the driving question for Unit 4. Use the third column of the DQ Notebook Worksheet to describe and reflect on how this new information has impacted your initial thinking about the driving question.

Jacqueline Howard Presents: The History of Money

Vocab Terms:

- barter

- credit

- digital

- exploration

- fiat money

- money

Summary

Prior to the existence of money, agricultural societies operated under systems of barter. Later, value was given to shells and to metals such as copper, silver, bronze, and gold, as coins and then paper became currency. The idea of credit developed during the Age of Exploration and evolved into the Gold Standard System and then modern systems, in which monetary transfers are primarily electronic.

Jacqueline Howard: The History of Money (5:22)

Key Ideas

Purpose

The development of money has had a huge impact on societies, and is a great example of how humans evolve socially. In this video, you’ll learn about how and why the literal trading of this for that has been replaced by the abstract notion of money.

Process

Preview

Jacqueline Howard discusses what exactly makes something money. What was money like in ancient times, and how did it evolve? And as we continue to move through this digital age, where is money headed?

Key Ideas—Factual

Think about the following questions as you watch the video:

- Prior to money, what system of exchange was used to obtain necessary goods?

- What were some of the first items to be bartered in early agricultural societies?

- Why did bartering societies move toward systems of money?

- What were some of the earliest forms of money?

- When and where did paper money originate?

- What brought about the use of credit as a system of monetary exchange?

- What is the Gold Standard System?

- The US dollar is fiat money. What does this mean?

Thinking Conceptually

With credit and debit cards, direct transfer, PayPal, and autopay, more and more monetary transactions are becoming digital. What do you foresee for the future of paper money? Will it ever go away completely? If it does, can you envision any problems that might arise in a world where no real money ever changes hands?

"One Lump or Two? The Development of a Global Economy"

Vocab Terms:

- consumer

- global

- Gold Standard System

- illegal

- luxury

- produce

Preparation

Summary

Both the trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific trade routes contributed to the development of a global economy that still exists in today’s world. Initially, Europeans were the chief controllers of this trade, even though they were not the producers of most of the goods being traded. Eventually, Asia was able to have a stake in these trade routes, but more as suppliers of goods rather than traders.

Purpose

In this article, networks of trade from the Far East to the Mediterranean are examined. While you learned a lot about interconnection and trade networks from the Columbian Exchange lesson, you did not learn about the economic systems that were created to support these developments or the specifics of certain kinds of trade. Understanding these systems helps us understand how Europe became the center of trading networks, and provides insight into the widespread development of capitalism.

Process

Skimming for Gist

How did we get from Christopher Columbus arriving in the New World to the 13 colonies? This article explains the systems that were developed to support new settlements and how capitalism contributed to the growth of exchange networks. In particular, this article focuses on the quest for silver and gold, and both the trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific trade.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Why was trade with Asia severely limited in the early sixteenth century?

- What were the goods that went from the New World to Spain from 1493-1550?

- How do historians know what goods were being traded during this time?

- Why is it significant that mercury was being sent to the New World?

- What was the trans-Pacific trade, and who controlled this trade?

- Why was silver eventually devalued over the world, and how did gold not get devalued?

- Who was the original European importer of tea and how did the British end up taking that over?

- Why was beaver the most valuable fur in the fur trade, who had access to this type of fur, and what is our evidence for knowing this?

Thinking Conceptually

How did the British and Europeans manage to place themselves at the center of trade networks even though they were not producing most of the goods being made? What are some of the impacts of this that can still be seen in the world today?

Systems of Exchange and Trade

Vocab Terms:

- exchange

- good

- port

- Silk Road

- trade

Summary

The Silk Road is one of the great exchange networks of human history. For much of the agrarian era, the Silk Road was in operation. The empires that profited from it came and went, but the Silk Road persisted, and was the forerunner for many of the systems of exchange and trade we have today.

Systems of Exchange and Trade (4:33)

Key Ideas

Purpose

In this video, you’ll learn about the important connection between how trade and transportations systems affected collective learning and the spread of goods, ideas, and diseases.

Process

Preview

As trade networks were established in Africa, Europe, and Asia, not only was there an explosion of trade of goods, but also of ideas, technologies, and diseases. This included the Silk Road, which connected the Afro-Eurasian zone. As this trade route became more established and people developed immunities to diseases, and increasingly sophisticated technologies, the Afro-Eurasian zone was poised to greatly expand its reach as the four global zones began to reconnect.

Key Ideas—Factual

Think about the following questions as you watch the video:

- What made the explosion of trade possible?

- What led to the initial demand that drove the creation of the Silk Road?

- What ended the Silk Road era?

Thinking Conceptually

Why was it necessary to have a stable empire for trade to flourish during antiquity? Be prepared to discuss your answer with the class.

“The First Silk Roads”

Vocab Terms:

- agrarian

- commercial

- empire

- exchange

- network

- Silk Road

Preparation

Summary

Exchange networks thrived in the agrarian era, when large empires could provide security and stability. The Silk Road is a great example of this. Both the first Silk Road era and the second Silk Road era were due in large part to the powerful empires in Rome, Persia, and China. Later, the Silk Road trade would flourish for a third time when the Mongols conquered much of Asia.

Purpose

It’s important to learn that exchange networks linked diverse cultures and moved products, as well as ideas and diseases. One of the first major exchange networks was the linking of Afro-Eurasia via the Silk Roads.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Exchange networks not only served to move products, but they also served as stimuli for innovation. A large exchange network, like the Silk Road, brought many diverse cultures into contact. Ideas and cultural practices moved with the products traded, as did disease.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Why was the linking of different civilizations through networks of exchange and trade an important process?

- What characteristics were important for the smooth operation of the Silk Road and which empires maintaind these characteristics?

- What are some of the goods that were in high demand and traded throughout the Afro-Eurasian world zone?

- What innovations in transportation technology made trade on the Silk Road possible?

- Why did the Silk Roads decline after the third century CE?

- Why did the Silk Roads revive after the seventh century CE?

- What effect did the Silk Roads and other networks of exchange and trade have on the development and power of the four world zones?

Thinking Conceptually

The Silk Roads allowed for the exchange of goods, ideas, and diseases across Afro-Eurasia. How would this be detrimental to the culture and civilizations in other world zones?

Claim Testing – Expansion and Interconnection

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, use your knowledge of claim testing to write supporting statements for claims. Claim testing is a skill that will not only help you decide what to believe, but can help you develop the capacity to convince others of particular arguments. By working on backing claims with supports, you’ll become more skilled at writing argumentative essays and using evidence to support your assertions.

Process

In this claim-testing activity, you are given four claims about expansion and interconnection. You are asked to work with these claims in three different ways:

- Find supporting statements for those claims.

- Evaluate the strength of the supporting statements provided for those claims.

- Provide statements that refute (argue against) the claims.

Get into small table groups. Each group should have a complete set of Claim Cards in the middle of their table. Listen for your teacher’s directions for when to start.

Round 1

- Grab one Claim Card from the center of the table.

- On the card, write down a statement that supports the claim. You can use prior knowledge or course materials for this.

- Pass your Claim Card to the person to your right.

- Write down a statement that supports the claim on the card that you now have. It can’t be the same as any of the supports already written on the card.

- Repeat the process until each group member has written a supporting statement on each card.

- Put the Claim Cards back in the center of the table.

Round 2

- Grab one Claim Card from the pile and stand up.

- Find at least three other students who have the same claim as you and get into a group with them (if there are more than six people in your group, let your teacher know).

- Look at all the supporting statements that were written for your claim. Decide which supporting statements are strongest (that is, they best support the claim).

- Write the strongest supporting statements on the whiteboard so everyone can see them.

Round 3

- With the same group you were in for Round 2, consider any historical exceptions to your claim. What can you offer to refute the claim?

- Add at least one refuting statement, what we often refer to as a counterclaim, on the board so everyone can see it.

- Present both your strongest supporting statements and the exception to the claim to the class—be sure to explain your reasoning for choosing your supporting statements and refutations.

Once you are done, your teacher may ask you to write a one- to two-paragraph mini-essay using one of the claims as a thesis statement. Then, you’ll use a few of the best supporting statements as evidence to support your thesis claim. Be sure to acknowledge the counterclaim or refuting statements in your mini-essay. For example:

- You might begin your mini-essay by stating the claim.

- Then, you should use the supporting statements you’ve identified as being the strongest to explain why this claim (thesis) is correct.

- Finally, you’ll acknowledge the counterclaim by including the strongest refuting statement you identified in the activity.

This activity will help you learn the best way to use supporting statements as evidence for a thesis statement, and how to acknowledge counterclaims in essay writing.

“Lost on the Silk Road”

Vocab Terms:

- caravan

- century

- cliff

- herdsman

- information

Preparation

Summary

The Silk Road posed a number of challenges to the traders who traversed the route. Their experiences helped them understand the best times to travel, the best paths to take, and the best way to deal with sudden changes in weather or the threat of raids. It was these challenges and others that goods, ideas, innovation, and collective learning had to overcome in order to spread throughout Afro-Eurasia, and eventually the world.

Purpose

By now you know about how the Silk Roads connected cultures and allowed for the exchange of goods and ideas; however, do you know how long and dangerous these roads could be? Peter Stark and his wife traveled along these roads to find out what obstacles early traders might have encountered.

Process

Skimming for Gist

The Silk Road is probably the best known and most famous of the exchange networks from the agrarian era. The Silk Road made it possible for members of the Roman upper classes to purchase Chinese silk in Roman markets. It also made possible the spread of ideas, and facilitated the spread of Buddhism to China from India. Descriptions of the importance of the Silk Road and the amount of trade that it carried sometimes overshadow descriptions of the challenges that traders faced on this route. The Silk Road took traders through mountains and deserts, and in some places made them vulnerable to attack by nomadic raiders.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are some of the challenges that Stark and his wife face throughout the story?

- How do you think traders, leading yaks loaded down with 300 pounds of goods, would have met these challenges?

- According to Stark, what were some of the goods, both material and nonmaterial, that were traded back and forth on the Silk Road?

Thinking Conceptually

As you learned in this reading, travel and trade along the Silk Road was dangerous. What types of goods were often traded along these routes and why? Be prepared to discuss your answers with the class.

The Navigator: Mau Piailug – Graphic Biography

Preparation

Summary

Hawaii was first settled by people from Tahiti, which is over 2,000 miles away. For most of the twentieth century, scholars claimed that the ancient Polynesians could only have achieved this voyage by accident, perhaps being blown off course in a storm. But in the 1970s, a group of Hawaiians set out to prove the scholars wrong. They built a traditional voyaging canoe and enlisted the help of a Micronesian man named Mau Piailug. Mau helped revive the lost voyaging knowledge that had helped ancient navigators cross thousands of miles of open ocean.

Purpose

Unit 8 is all about how human societies expanded and developed interconnections with each other. The Polynesian migrations that started over a thousand years ago were a big part of this story. They expanded and maintained connections with each other across thousands of miles of open ocean. Their feats of navigation relied on centuries of collective learning and knowledge passed on through oral tradition. But by the twentieth century, these traditions had all but disappeared. Mau Piailug helped revive this tradition. This biography is proof that collective learning doesn’t develop in a straight line.

Process

Read 1: Observe

As you read this graphic biography for the first time, review the Read 1: Observe section of your Three Close Reads for Graphic Bios Tool. Be sure to record one question in the thought bubble on the top-right. You don’t need to write anything else down. However, if you’d like to record your observations, feel free to do so on scrap paper.

Read 2: Understand

On the tool, summarize the main idea of the comic and provide two pieces of evidence that helped you understand the creator’s main idea. You can do this only in writing or you can get creative with some art. Some of the evidence you find may come in the form of text (words). But other evidence will come in the form of art (images). You should read the text looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the main idea, and key supporting details. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What misconception did the Hawaiians who built the Hōkūleʻa want to change?

- Why was planning the voyage of the Hōkūleʻa so challenging?

- What methods did Polynesian navigators use and how was their knowledge passed down?

- What information does the attached comic, “Aka’s Voyage for Red Feathers” add to the story of Mau Piailug? Why would this story have been useful for Polynesian navigators to learn?

- How has the artist designed the page, text, and illustrations to tell you about Mau’s story and the story of Polynesian navigators in general?

Read 3: Connect

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in this unit of the course. On the bottom of the tool, record what you learned about this person’s life and how it relates to what you’re learning.

- Can you think of any knowledge that you use in your own life that was passed down to you verbally? Maybe through a family member or older person in your community?

- Mau’s biography is a story of collective learning. How does it change what you’ve heard about collective learning so far in the course?

To Be Continued…

On the second page of the tool, your teacher might ask you to extend the graphic biography to a second page. This is where you can draw and write what you think might come next. Here, you can become a co-creator of this graphic biography!

A Curious Case: African Agrarianism

Vocab Terms:

- agrarian

- agriculture

- kingdom

- settlement

Preparation

Summary

Compared to other world regions like the Fertile Crescent, the parts of Africa below the Sahara and Sahel adopted agriculture relatively late in human history. After the adoption began, the first states began appearing in Central and South Africa. While these states clustered in dense populations and supported divisions of labor, they did not reach empire status like the agrarian civilizations in West Africa and Egypt. As it was, the late start of agriculture in the region meant that Central and South Africa’s independent story was interrupted by the larger story that was driving the world closer together—the unification of the world zones.

Purpose

This reading will help you gain an understanding of the delayed start of agriculture in Central and South Africa and the effects of that delay.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Agriculture began later in Central and South Africa below the Sahara and Sahel than it did in other parts of the world. We only see the first glimmer of agrarian civilizations begin to emerge in the region from 1000 to 1500 CE. The development of these civilizations was interrupted in most cases by the expansion of older human societies.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions about the origins of agriculture in Africa:

- Why do states often take so long to form after the adoption of agriculture?

- What were some of the benefits of foraging? Why did some groups of people remain foragers far longer than others?

- What are some of the characteristics of complex agricultural societies?

- What implications did getting a “late” start in agriculture have for Central and South African societies?

Thinking Conceptually

The end of this article debates whether or not, in the big picture of human history, the people of Central and South Africa were better off for the relatively late arrival of agriculture to their region, or if it has left them at a disadvantage moving forward. Where do you fall in this debate?

Personal Supply Chain

Preparation

Purpose

Improvements in travel and communication over the last 500 years have led to the interconnection of the four world zones, but what does this mean for us today? In this activity, you’ll research an item you use every day in order to understand how this item is made, how long it takes to travel to the area where you live, and how much energy is needed in this process.

Process

Choose an item you use in your daily lives. Research the raw materials needed to make it and how these raw materials come together to form the finished product. You’ll also research what kind of transportation is used to get the final product to you, and complete a map to mark the places where your item is produced and where it must travel to get to you.

Your research will specifically answer the following questions:

- What are the raw materials needed for this product? Where are they found?

- What are the steps involved in making this product? Where does each step in the production take place?

- What energy is needed to produce this item? Where does that energy come from?

- What kind of transportation, if any, is needed at each stage of the production process, including getting the finished product to you?

After completing the research and filling out the worksheet and map, your teacher will pair you up with another student. Take about 5 minutes to look at your classmates’ work and answer the following questions, after which your classmate will do the same for your work:

- What is the most surprising discovery you made in your research?

- What is the most surprising discovery you see in the work of your classmates?

- What does this tell you about the importance of interconnection today?

Little Big History Final Project

Preparation

Purpose

This is the last structured Little Big History activity before the final presentations. It’s important for you to work through the activity in order to narrow down the subject of your paper and to choose how you would like to present it.

Process

In this activity, you’ll learn about the final LBH project criteria. Then, you’ll use the criteria and rubrics to evaluate what you’ve completed for your LBH project to date, and what you still have left to do.

Your teacher will walk you through the LBH Project Description and the checklists and rubrics you’ll be using for the project. One important thing to remember is that you’ll be writing an individual paper that is an extension of the biography of your Little Big History object essay. For this essay, you’ll take one of the research questions that your group created (and your teacher approved) in LBH Part 5, and write a longer essay based on that. You should pick a question that will help you explore an area of the topic that is of particular interest to you.

Another important thing to remember is that you’ll be doing a presentation about your LBH object. Your teacher will decide on your options, but these are two possibilities: In the first option, you’ll create what’s called a World Without presentation. Your group will use your collective knowledge of your object and its historical impact to tell the story of what might have happened if your LBH object did not exist. How would the world be different? Would this have an impact on future thresholds? Your group should be as creative as possible and have fun with this. However, remember that even though this should be fun and creative, you still have to meet the criteria for the project as laid out in the rubric.

Alternatively, your teacher might give you the option of doing a service project related to your LBH object instead of the World Without presentation. For an LBH service project, you’ll think about what you have learned about your object, its impact upon the world, and what you could do in relationship to that object to make the world a better place. For example, if you decided to do the LBH of water, you might learn about how people around the world don’t have clean water, and you might raise money to fund water sanitation solutions in areas in which they don’t exist.

After you’ve reviewed the rubrics with your teacher, do the following with your LBH group:

- Refer to the research questions you generated in LBH Part 5. Decide who is going to explore which question in more depth as an extension of the biography of the LBH that you’ve already written about your object.

- As a group, use the Big History Writing Rubric to re-evaluate your LBH object biography. You’ll use the biography as a launching point for your individual papers, so based on that review, ask yourselves if there’s anything missing from this biography that should be added to your individual papers. Is there any thinking in your original papers that should be revised? What might you add or revise based on your individual questions?

- Brainstorm your World Without projects. Come up with a few ideas about what might have happened differently and what your final product might look like in light of these ideas. Or, use this time to brainstorm your service projects. Before you leave class, turn in a list of World Without or service project ideas to your teacher.

“She Blinded Me with Science: Collective Learning and the Emergence of Modern Science”

Vocab Terms:

- collective learning

- doctrine

- network

- revolution

- scientific

- theory

Preparation

Summary

As the world became interconnected through increased trade routes, collective learning accelerated due to the interconnectedness of people and ideas. Through this spread of ideas, modern science emerged, leading to the scientific methods that we still use in today’s world.

Purpose

In this article, a historian provides an account of how she examined the birth of modern day science and the European Scientific Revolution. This journal entry gives you another window into how historians draw conclusions about the past, which should help you when drawing your own conclusions about history. In addition, thinking about the progression of collective learning in terms of the birth of modern science should add to your understanding of the development of science in human history.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Starting in the fourteenth century, the acceleration of global exchange networks led to the formation of new ideas in science as well as new scientific advances. These networks encouraged new ideas and new ways of thinking since people had more sources of information from which to draw conclusions. In addition, these new sources of information helped scientists in explaining new scientific phenomena to the world.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What are David Christian’s rules of collective learning?

- How did Europeans have an advantage in the sixteenth century when it came to new knowledge?

- What are the steps that made the “Scientific Revolution” more of a revolution of thought processes rather than just a discovery of more scientific information?

- How do the excerpts from Copernicus’s “The Earth Moves” reflect the steps of the scientific process?

- What technique, which is now the gold standard for scientific proof, did the author use to help prove that worms do not come from decaying bodies

- How did scientists such as Copernicus and Redi help usher in the Age of Enlightenment?

Thinking Conceptually

At the end of the third close read, think about the following questions: Does Ravi’s method of drawing conclusions about history mimic the scientific method that she discusses in the article? How is her historical method the same as the scientific method, and how is it different?

"Thank You for Algebra: Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi"

Vocab Terms:

- caliph

- inheritance

- manuscript

- optics

- revolutionize

Preparation

Summary

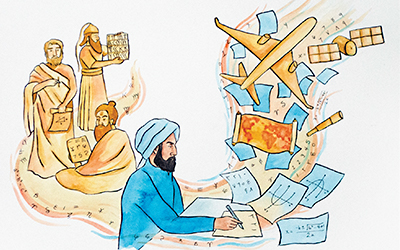

You might not be super excited about learning algebra, but it has helped lead to innovations that probably affect your life. For those—and for your algebra class—you should thank a man named Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi. He was a ninth-century scholar in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom. There, he wrote books about mathematics that promoted algebra and algorithms. He brought the ancient Hindu numbering system—a version of which we use today—to the Islamic world. These numerals, and the other advances al-Khwarizmi made, spread widely and laid the foundations for many later scientific advances.

Purpose

This article about al-Khwarizmi introduces the idea of collective learning in mathematics. The way we do math—even down the numbers we use—is thanks to centuries of shared knowledge passed between scholars in different societies. By focusing on al-Khwarizmi, this article also highlights the contributions of Muslim scholars to modern mathematics and science.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, analysis and evidence, and claim testers. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Who was al-Khwarizmi and what contributions did he make?

- According to the author, why is algebra important?

- Why was al-Khwarizmi’s adoption of the Hindu numbering system important?

- What was the House of Wisdom? Why was it important? What happened to it?

- Look at the art at the top of this article. How would you describe what you see to someone? How does it help to illustrate some of the issues and arguments in your answers to the first four questions?

Thinking Conceptually

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- You’ve heard quite a bit about collective learning by this point in the course. What are some things that you do on a daily basis that were made possible by the work of al-Khwarizmi? How are you a part of the story of collective learning?

Benjamin Banneker: Science in Adversity

Vocab Terms:

- astronomy

- contribute

- indentured servant

- inequality

- knowledge

Preparation

Summary

Benjamin Banneker, born in Baltimore County in 1731, was a largely self-taught academic whose passions were mathematics and astronomy. As a result of the social prejudices of the time, he was not afforded the opportunities of organized, higher education and lived the majority of his life as a tobacco farmer and private scholar instead of a major contributor to or benefactor from collective learning. Nevertheless, Banneker’s contributions to science were far-reaching, among them a yearly almanac that calculated the tides, phases of the moon, occurrences of eclipses, and other natural events.

Purpose

This reading will help you gain an understanding of the life and accomplishments of one of the first African-American scientists, Benjamin Banneker.

Process

Skimming for Gist

Benjamin Banneker was an expert in a number of areas, including mathematics and astronomy. He is widely regarded as one of the first African-American scientists, and as a gifted figure during the Age of Enlightenment. He was very accomplished, but undoubtedly held back by the prejudices of the time.

Understanding Content

By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions about the life of Benjamin Banneker:

- What does the story of Molly and Banneker tell us about the time in which they lived, and how the inequalities of the period affected collective learning?

- What was Banneker’s greatest contribution to science?

- Explain Banneker’s exchange of letters with Thomas Jefferson. What arguments did Banneker use to try to convince Jefferson he was wrong?

- How did Banneker’s circumstances make it difficult for him to contribute to the pool of human knowledge?

- What were some of the unique ways in which Banneker went about acquiring knowledge and doing studies?

Thinking Conceptually

Benjamin Banneker, his parents, and his grandparents are proof that the collective learning of humanity is robbed of the contribution of many gifted people when society succumbs to corruption, prejudice, and intolerance. Can you think of other cultures that are currently in the state that colonial America was in during the time of Benjamin Banneker, for example, through apartheid or gender discrimination?

Debate: Has the Scientific Revolution Ended?

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, you’ll think about whether or not the Scientific Revolution has ever ended. Thinking about the progress of science prior to the Age of Enlightenment and the progress since helps you consider what counts as science, what makes a revolution, and if it’s possible for a revolution to go on for over 300 years. In addition, this debate should get you to reflect on what is currently happening in science, which will help you see how you’re a part of historical narratives.

Process

Your teacher will divide your class into two position groups: the Scientific Revolution is dead (Group 1); and the Scientific Revolution is alive (Group 2). One group will argue that the Scientific Revolution ended, and the other will argue that it has not. Each group is responsible for researching its position and preparing an argument to support its point of view. You may use any of the information provided in the course as well as your own research to make your points.

Questions you might consider in preparing your argument:

- What counts as science?

- Who are the scientists?

- What is a revolution?

- How do you define a scientific revolution?

- Can a revolution really last for 300 years?

- How do we know if we are in the midst of a revolution?

- How do we know when something in history began and ended?

Remember to use the Debate Prep Worksheet to help prepare for the debate. Don’t forget to review the Debate Format Guide so you’re aware of how much time you have for each section of the debate. It’s also helpful to revisit the Debate Rubric as you prepare since this will help ensure you meet all debate criteria. Your teacher will likely use the Debate Rubric to decide which group argued their position more effectively.

Revising Investigation Writing – Sentence Starters Part 2

Preparation

Purpose

This is another activity where you’ll examine a piece of writing through the lens of the entire BHP writing rubric. While the categories in the rubric are a useful tool for initially understanding the different elements of writing, ultimately, it’s best to take it as a whole since the areas of focus are interrelated. In the interest of continued skill-building and independence in completing this type of work, this time you’ll conduct analysis and revision alone instead of groups. And for this activity, you’ll be reviewing a peer essay - and a peer will be reviewing your essay!

Practices

Reading, claim testing

In this activity, you must engage in close reading so that you can revise an essay. Claim testing is a process that at this point should be a routine part of your classroom practice: When reading historical writing, you need to analyze whether or not assertions are supported with evidence. When constructing historical writing, you should claim test your own assertions to make sure they are sufficiently supported.

Process

This Investigation writing activity is going to be a lot like the last one you did. However, this time you’re going to revise one of your classmate’s essays. And, you’ll work alone instead of in groups. Remember, instead of just looking at one row from BHP Writing Rubric, you’re going to revise text using each of the three areas you’ve been focusing on: Claim and Focus, Analysis and Evidence, and Applying BHP Concepts. You should also think about Organization, something you initially focused on way back in Unit 2!

As in the last Investigation writing activity, your teacher will give you a set of sentence starters to help with your revisions. Look at the Revising Investigation Writing – Sentence Starters Part 2 Worksheet and read the peer essay given to you by your teacher. While reading, keep Claim and Focus, Analysis and Evidence, and Applying BHP Concepts in mind. Once you’ve reviewed the essay, underline what you think the major claim or thesis is. If needed, improve the thesis statement using one of the sentence starters provided. If the major claim is as good as it can get, point out the features of the claim that make it outstanding. Once you’ve done that, circle anywhere texts were used as evidence, and then rewrite one of those sentences using one of the sentence starters provided. Finally, highlight anywhere BHP concepts were applied, and use yet another sentence starter to improve any statements where BHP concepts were applied.

Once you’ve completed your worksheet, pair up with the classmate whose essay you read, and share your feedback and suggestions for improvement. Investigation 8 is up next, and you should use the sentence starters and what you’ve learned from the analysis and revision process when writing your Investigation 8 essay.

Investigation 8

Preparation

Investigation 8 Prompt: How and why have our reaction and response to disease changed?

Purpose

This Investigation asks you to use comparison as a tool to examine the same phenomenon—plague—at two different points in time. By comparing these events, you can analyze the way changes in collective learning have shaped our reaction to disease. Additionally, this assessment helps prepare you for document-based questions you will encounter on standardized exams.

Process

Day 1

In this activity, you’re going to respond to a question using texts to support your thinking in the form of an Investigation. In this course, Investigations give you a question along with several source documents, and you will use the information in those documents (and perhaps additional knowledge) to respond to the question. Your responses will be written in essay format, and will be five- or six-paragraphs long. This Investigation asks you to respond to question, How and why do individuals change their minds?

First, your teacher will ask you to write down your conjectures—or your best guesses made without lots of evidence—about the following questions: When and why do you think people should change their minds, particularly about things that most other people believe? What do you think made Copernicus and Galileo change their minds about the Earth being the center of the Universe?

You’ll have about 5 to 10 minutes to make notes and think about what causes individuals to change their minds.

With your class or in small groups, share your list of ideas about why people change their minds. Next, your teacher will either hand out or have you download the Investigation 2 Document Library. As you review each document, you’ll use the graphic organizer to record the major claims about the structure of the Universe in the texts and to document which claim testers support those claims.

Day 2

Now it’s time to write! You’ll develop a five- to six-paragraph essay arguing how and why individuals change their minds, using evidence from the case study of Copernicus and Galileo to support your argument. Remember to use information from the Investigation 2 Document Library along with BHP concepts and other information you’ve learned in this unit as evidence to support your argument or opposing point of view. It’s also important that you cite the sources you use as evidence in your essay.

Investigation Writing Samples

Preparation

Purpose

In order to improve your writing skills, it is important to read examples—both good and bad—written by other people. Reviewing writing samples will help you develop and practice your own skills in order to better understand what makes for a strong essay.

Process

Your teacher will provide sample essays for this unit’s Investigation prompt and provide instructions for how you will use them to refine your writing skills. Whether you’re working with a high-level example or improving on a not-so-great essay, we recommend having the BHP Writing Rubric on hand to help better understand how you can improve your own writing. As you work to identify and improve upon aspects of a sample essay, you’ll also be developing your own historical writing skills!