4.3 A Dark Age?

-

12 Activities

-

9 Articles

-

3 Videos

-

5 Visual Aids

-

1 Assessment

Update ahead! This course will be updated soon. See what's changing.

Introduction

The question mark is not at indication that we don’t know what this lesson is about. Rather, we think the “The Dark Ages” has a branding problem, as historians have long debated how the Middle Ages in Europe should be characterized. The sun shone as bright then as it does now, but the number of surviving sources that could tell us about people’s everyday lives are far fewer than in earlier and later periods. Besides, we will go well beyond Europe as we examine Japan’s political structure, trade along the Indian Ocean, and experience the changing expectations for women in both China and Medieval Europe. This lesson even offers an opportunity to revise some historical writing to show how claim and focus bring us closer to the real narrative.

Learning Objectives

- Examine the impact of the collapse of empires and the formation of new political organizational efforts such as the feudal system.

- Critique the historical narrative of the “Dark Ages.”

- Explain how the Crusades impacted exchange networks during this era.

- Analyze how the “Dark Ages” impacted the production and distribution of goods, trade networks, and cultural exchanges.

- Utilize the historical thinking practice of sourcing to evaluate an imperial edict from a Chinese emperor.

- Evaluate and compare the roles of women in medieval Europe and Song China.

- Use a graphic biography as a microhistory to support, extend, or challenge the overarching narratives from this time period.

- Identify organization, language, and style in historical writing.

- Create and support arguments using historical evidence to evaluate how states responded to the collapse of the Roman Empire and Han dynasty China.

What Were the Dark Ages?

Preparation

Purpose

In this lesson, you are introduced to the term “Dark Ages”, which is the label that was generally used by historians periodizing this time in history. This quick opening activity will get you to think about what the “Dark Ages” means, so you can consider what happens when historians label the past in particular ways.

Process

You are getting ready to study a period of time that most historians used to call the Dark Ages. Historians periodize history into chunks of time based on a number of factors including artifacts or tools that were used in a certain time, or the rise and fall of empires, or times of artistic or scientific achievement. The Dark Ages once referred to the period of time after the fall of the Roman Empire to the start of the Renaissance and the “Age of Discovery”. In addition, this periodization only concentrates on one region of the world: Europe. In small groups, brainstorm what comes to mind when you hear this term. In particular, consider:

- Why do you think historians might have labeled or periodized this time as being “dark”?

- What might be “dark” about communities in this time period?

- What might be “dark” about networks in this time period?

- What might be “dark” about production and distribution in this time period?

The “Dark Ages” Debate

Vocab Terms:

- antiquity

- Enlightenment

- humanist

- regress

- Renaissance

Preparation

Summary

For many centuries, the idea that the Middle Ages were “dark” was pretty common. This idea was born in the fourteenth century and was widely accepted until the nineteenth century. Many scholars thought of the Middle Ages as a period where nothing really happened and culture and intellectual achievement declined. But recently, scholars have been pushing back against this trend, asking: Were the so-called “Dark Ages” really all that dark?

Purpose

In this article, you’ll read about how different authors approach the idea of a “Dark Age” during the medieval period. This will help you think about the Era 4 Problem: How do human systems restructure themselves after political, environmental, or demographic catastrophe? You’ll explore authors’ historical contexts in order to understand what influenced their ideas about the medieval period. This provides you with a usable history, since ideas about dark and golden ages are common in many kinds of communities, including national and religious communities.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Who first described Europe after the fall of Rome as being “dark” or backward?

- What was Edward Gibbon’s contribution to the idea of a “dark age?”

- How might English Heritage’s description of Tintagel Castle provide evidence against the idea of a “dark age?”

- What does Alban Gautier think of the term “Dark Ages?” What two limits does he think it has?

- How were the views of eighteenth-century authors, like Edward Gibbon, shaped by the times they lived in? How did this compare to nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century views?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- This article references ways that scholars have used the idea of a European dark age to suit their own views and goals. Can you think of any ways that people today might use the idea of a dark age (or golden age) to suit their own agendas?

Was There Ever a ‘Dark Age’?

Vocab Terms:

- aristocracy

- clergy

- feudal contract

- feudalism

Preparation

Summary

This article questions whether there were extended periods in Era 4 that could be described as “dark ages” in Afro-Eurasia. It looks at Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire, China after the fall of the Han Dynasty, Mongolian society, the Abbasid Empire, Southeast Asia, and West Africa, showing how interconnections among societies persisted and even grew in some parts of Afro-Eurasia.

Purpose

This article tests the claim that there was a “Dark Age” in Afro-Eurasia during Era 4. Thinking through this claim, will help you respond to the Era 4 problem in two ways. First, you’ll be able to think about how the label “dark age” can be both useful and inaccurate. Second, you’ll consider how interconnections among human societies grew and shrunk over Era 4. It’ll provide evidence which may—or may not—support the production and distribution narrative frame.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What were the political effects of the fall of the Roman Empire? What organized European communities after the Empire?

- How did relationships form the basis of feudalism?

- What intellectual achievements occurred during the medieval period?

- How do cities provide evidence that medieval Europe wasn’t experiencing a dark age?

- Did China have a Dark Age?

- Name one society mentioned in this article that you think didn’t experience a Dark Age. What evidence can you provide to defend your claim?

- How did the Afro-Eurasian population change from 476 to 1176 CE? What might this indicate?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- How would evidence from this article extend, support, or challenge the production and distribution frame?

- What does the author of this article argue about the label of the medieval “Dark Age”? Does the author consider it useful and accurate? Do you find the author’s argument convincing? Why or why not?

Naming This Time Period

Preparation

Purpose

Now that you have studied what many historians of the past have often called the Dark Ages, and have discovered that this label might not be suitable at all, you have the opportunity to come up with a name that is more appropriate for this period in history. This will allow you to reflect on why Dark Ages is a misnomer, and how periodizing and labeling the past can highlight particular trends while obscuring others, perhaps giving us an incomplete picture, or even a single story, about events in history.

Process

The Dark Ages once referred to the period of time after the fall of the Roman Empire to the start of the Renaissance and the “Age of Discovery”. As you now know, this periodization only concentrates on one region of the world: Europe, therefore obscuring what was going on with the rest of the world at the time.

In small groups, your job is to rename the Dark Ages to something more suitable for the time period. To do this, you need to provide the exact timeframe, a name, and evidence as to why your name is the best. Remind to try to create a name that is truly global and therefore gives a better sense of what was happening around the world at this time, not in just one location. Note: You should also avoid simply labeling it the Middle Ages or Medieval, which also generally refers to this period of time in Europe. Take out the Naming This Time Period Worksheet and answer the questions and construct an argument for why your name is better than the “Dark Ages” that historians of the past used. Be prepared to present your name and evidence for why yours is the best way to name this time period.

Shoguns, Samurai and the Japanese Middle Ages

Vocab Terms:

- bakufu system

- feudal system

- samurai

- shogun

- shogunate

Summary

This video gives an overview of Japanese political history during the medieval period. As power became decentralized and then centralized again, different classes in society rose to prominence. As the emperor lost political influence, military rulers and warriors called daimyo and samurai rose to power.

Shoguns, Samurai and the Japanese Middle Ages (6:26)

Key Ideas

Purpose

In this video, you’ll see how Japan’s political system both changed and stayed the same. You’ll find evidence to help you compare Japanese society to other societies. This evidence will also enable you to support, extend, or challenge the communities narrative frame. This video will help you think about the Era 4 problem in two ways. First, you’ll have some new information to help you think about whether Japan suffered societal collapse. Second, you’ll be able to consider how interconnections within and beyond Japan changed over the Era.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- Beginning around the late twelfth century, what class became increasingly powerful? Who lost power?

- What new political system emerged around this time?

- Was power centralized the shogunate or bakufu system? Who held power under this system?

- What are some similarities between the bakufu system in Japan and feudalism in Europe?

- What did guns have to do with Japanese reunification?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- During Era 4, did Japan experience societal collapse? Did connections among communities in Japan increase or decrease?

- You’ve read about collapse and recovery all over the huge connected landmass of Afro-Eurasia. Can you think of any ways that the small island of Japan might have been influenced by decline and recovery in the rest of Afro-Eurasia?

China Under the Tang and Ming Dynasties

Vocab Terms:

- ancestor veneration

- Buddhism

- Confucianism

- Daoism

Preparation

Summary

China went through a “golden age” during the Tang Dynasty, but that doesn’t mean that there was a dark period afterward. In fact, the later Ming dynasty continued to have flourishing trade and agricultural production. It even expanded China’s borders to new territory. But both the Tang and Ming ultimately declined and fell.

Purpose

In this article, you’ll read about how trade changed under the Tang and Ming dynasties, allowing you to challenge, support, or extend the networks as well as the production and distribution frame narratives. You’ll also be able to track patterns of continuity and change, which will help you respond to the Era 4 problem about societal collapse. In particular, you’ll read about how the Ming continued the work of earlier dynasties and how they ultimately declined themselves.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did belief systems influence communities in China during this period?

- What were some of Empress Wu’s accomplishments?

- How did increased trade affect China?

- How did oceanic trade change under the Ming? How was it different from European oceanic exploration?

- What was agricultural production like under the Ming, and how did this affect the population?

- What caused the fall of the Ming dynasty?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- In Era 4, China was one of the most populous, powerful, and wealthy empires in the world. What might China’s history suggest about the broader trends of recovery and decline across Afro-Eurasia?

Sourcing – “An Imperial Edict Restraining Officials from Evil”

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, you will continue to develop your sourcing skills by analyzing a primary source document written by the Ming emperor Hongwu, in which the author attempts to influence the behavior of his subjects and officials. Assessing the point of view and the intended audience of a source is essential to understanding how to evaluate the credibility of the source and motives of the author. You will further develop your sourcing skills by working in groups to answer a prompt, incorporating elements of audience and point of view in your answer.

Practices

Claim testing

Your claim-testing skills will be put to use as you evaluate the document based upon your intuition, logic, the authority of the source, and historical evidence. This will help you establish the and the credibility of the source by examining the point of view and intended audience.

Process

In this activity, you will read a primary source excerpt, complete the Sourcing Tool focusing on audience and point of view, and write a response to a prompt.

Your teacher will either hand out or have you download the Sourcing Tool and “An Imperial Edict Restraining Officials from Evil” excerpts (both are included in the Sourcing—An Imperial Edict Restraining Officials from Evil worksheet). Follow your teacher’s directions and read the primary source excerpts starting with the introductory paragraph about the life of Hongwu. As you read, think about the question, How did the Ming emperor attempt to maintain order and control of his empire?

After you’ve finished reading the excerpts, your teacher will break the class into small groups to complete the Audience and Point of View rows of the tool.

Next, work with your group to write a brief response (two to four sentences) that answers the question posed earlier: How did the Ming emperor attempt to maintain order and control of his empire? Your paragraphs should make specific reference to the Audience and Point of View portions of the tool, but can include other categories as well. Be prepared to share your responses with the class and discuss how this text supported, extended, or challenged the information you’ve learned thus far in the course.

As an extension, your teacher may ask you to answer the questions in the Why? (Importance) row of the tool on your own to turn in as an exit ticket.

Your teacher will collect your worksheets and responses to evaluate how your sourcing skills are progressing.

International Commerce, Snorkeling Camels, and Indian Ocean Trade

Vocab Terms:

- bulk goods

- monsoon

- monsoon marketplace

- self-regulated market

Summary

Indian Ocean trade—or, as John Green calls it, the “Monsoon Marketplace”—was bigger, richer, and more diverse than the Silk Road. It totally transformed production and distribution, communities, and networks in Africa and Asia. Merchants moved with monsoon winds carrying goods, technologies, and ideas to faraway places, connecting many societies to one another.

International Commerce, Snorkeling Camels, and the Indian Ocean Trade: Crash Course World History #18 (10:14)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video will help you respond to the Era 4 problem by exploring how Indian Ocean trade forged interconnections among societies in Asia and Africa and how these interconnections changed over the Era. These connections provide evidence to evaluate the networks, production and distribution, and communities frame narratives. This video will help you make comparisons between sea trade and overland trade routes, specifically the Silk Road. As you watch, evaluate John Green’s argument about how trade causes big social and political changes.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- According to John Green, how did Indian Ocean trade compare to the Silk Road?

- Why does John Green describe Indian Ocean trade as a ‘Monsoon Marketplace?’ What was the significance of monsoons?

- Who controlled how Indian ocean trade worked and protected trade routes?

- What traveled across long distances because of Indian Ocean trade?

- Why did Islam spread to Indonesia more than to Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, or Vietnam?

- How did cities along Indian Ocean trade routes benefit from trade? What were some downsides?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- John Green questions whether “states and governments and the funny-hatted people who rule them are the real movers and shakers in history”. He ends the video by claiming, “it’s almost as if the merchants decide where the people with the funny hats go, rather than the other way around.” Do you find his evidence for this convincing? What about today? Do politicians control business or does it ever work the other way around?

EP Notebook

Preparation

Make sure you have the EP Notebook worksheets that you partially filled out earlier in the era.

Purpose

This is a continuation of the EP Notebook activity that you started in this era. As part of WHP, you are asked to revisit the Era Problems in order to maintain a connection to the core themes of the course. Because this is the second time you’re working with this era’s problems, you are asked to explain how your understanding of the era’s core concepts has changed over the unit. Make sure you use evidence from this era and sound reasoning in your answers.

Process

Fill out the second table on your partially completed worksheet from earlier in the era. Be prepared to talk about your ideas with your class.

Impact of the Crusades

Vocab Terms:

- bequeath

- Crusades

- feudal system

- pagan

- Reconquista

Summary

The Crusades pitted societies against each other and exacted a massive death toll. So you might be surprised to hear that they also increased interconnections within and among societies. European political communities were totally reorganized. At the same time, the movement of warriors and merchants also moved ideas and increased trade, which helped trading cities like Venice grow into powerful city-states.

Impact of the Crusades (6:46)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video provides evidence at the regional level to respond to the Era Problem: How do human systems restructure themselves after political, environmental, or demographic catastrophe? Though the Crusades devastated places like Constantinople, they also led to increasing interconnections which fostered trade and the transfer of knowledge. You can use the evidence in this video to analyze these transformations using the networks and communities frames.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- How did the population of Muslims and Jews in Europe change during the Crusades?

- Which leaders gained power as a result of the Crusades and why?

- How did the Crusades affect cities? How did major trading cities play a role in the Crusades?

- What kinds of exchanges happened as a result of the Crusades?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- As a result of the Crusades, which societies were pushed further apart? Which societies became more connected? Use evidence from this video and from other articles and videos in this Era to defend your claim. Consider connections at different scales, like between European societies, between different religions, and between European and Muslim states, for example.

Comparison – Women in Medieval Europe and Song China

Preparation

Purpose

The experiences of women throughout history might differ between regions and time periods. However, through historical investigation, including comparison, we can view how women in history confronted similar challenges and common social expectations, regardless of place and time. By zooming in on the stories of women in specific societies, we can better understand the challenges women faced throughout history and, in many parts of the world, continue to face today. Through comparing the experiences of women across different regions and time periods, we can see how societies constructed the roles and status of women within them, perhaps learning to question the ways in which women’s roles are defined today.

Practices

Contextualization, CCOT

While the primary focus in this activity is comparing the experiences of women in specific regions and times, you will examine the context in which women’s roles were constructed and identify who had the power to define women’s roles and status in each instance. Additionally, you will need to identify how women’s roles stayed the same (continuity) and changed compared to women’s roles today.

Process

In this activity, you’re going to compare women in different regions during similar times in history. Ultimately, you will think about how the roles of women in different places compare to the roles of women in your life today.

Your teacher will assign you an article to read, either “Medieval Women in Western Europe, c. 1000–1350 CE” or “Women in the Song Dynasty of China, 960–1279 CE.” As you read your assigned article, answer the questions in Part 1: Identifying and Describing of the Comparison Tool, which is included with the worksheet. Then, your teacher will pair you with a student who read a different article, and you’ll work together to complete the similarities and differences column of the tool.

Once you and your partner have completed Part 1 of the tool, you’ll work together on Part 2: Analyzing to write two thesis statements in response to the following prompts.

- What was the most significant similarity between women’s experiences in medieval Europe and Song Dynasty China?

- What was the most significant difference between women’s experiences in medieval Europe and Song Dynasty China?

Remember that you can use the acronym ADE (amount, depth, and endurance) to help determine historical significance. Consider if all women were affected by these similarities and differences (amount); if women were deeply affected by these similarities and differences (depth); or if these similarities and differences were long lasting (endurance).

After you’re finished writing your thesis statements, join with another pair of students to form a group of four. Share and discuss your thesis statements in your new group and build upon or revise your thesis statements based on these discussions.

Then, you’ll return to your seats and individually write an exit slip on the back of your worksheet answering the following questions (remember to support your answers with evidence from this activity):

- Considering the roles of women in these societies, which society was the most desirable for women? Why?

- If we compare medieval Europe and Song China to today’s society, how have women’s roles changed and how have they stayed the same?

Turn in your worksheet at the end of class so your teacher can assess how your comparison skills are progressing.

Medieval Women in Western Europe, c. 1000–1350 CE

Vocab Terms:

- abbess

- anchoress

- Catholicism

- celibacy

- convent

- monastic

Preparation

Summary

Religious beliefs and customs structured medieval European communities. So, it’s no surprise that religious practices and prejudices shaped the lives of Christian and Jewish women in medieval Europe. Medieval society limited women’s roles in public life. The lives of nobles, nuns, peasants, and urban dwellers alike were all structured around, and limited by, religious beliefs.

Purpose

This article explores the impact of religion—specifically Christianity and Judaism—on women’s lives in medieval Europe. It provides evidence to consider the link between belief systems, social and gender hierarchies, and systems of production and distribution. The article will help you evaluate both the communities and production and distribution frame narratives in this era. As you read, keep an eye out for how gender roles changed as Christianity gained more influence.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did social status affect women’s roles in medieval Europe? Provide an example for women’s roles in the upper, middle, and lower classes of medieval Europe.

- How did the Biblical story of Adam and Eve affect women in this period?

- How did nuns lives change from the seventh to the fourteenth century?

- Why were nuns in convents mainly from the upper classes?

- How did the seating structure of the Catholic mass reinforce both social and gender hierarchies in medieval Europe?

- Why did most Jewish women live in urban areas, and often in Jewish neighborhoods?

- How were Christian and Jewish women’s roles similar and different?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- This article gives you some sense of the roles women played in religious communities and in production and distribution. How do you think all the expansion and contraction of networks that you’ve read about in this unit affected women? What roles might women have played in rebuilding networks?

Women in the Song Dynasty of China, 960–1279 CE

Vocab Terms:

- Confucianism

- dowry

- foot binding

- Neo-Confucianism

- subservient

Preparation

Summary

While the Song Dynasty ruled, a population boom, an increase in trade, and new innovations produced an era of prosperity in China. Women of the elite classes may have benefitted from China’s new wealth, but women in general were still viewed as the inferior sex. Confucianism and cultural practices like foot binding constrained elite women’s roles in public life. Women of the lower classes had more freedom of movement, but their station in society remained restricted by belief systems and social customs.

Purpose

This article examines the impact of belief systems and social structures on women’s roles in society. This will help you analyze and compare the lives of women in Song China with those of women in medieval Western Europe, providing you with evidence to identify the similarities and differences between women’s roles in two geographic regions. This will aid in your assessment of the communities frame narrative and women’s place within it.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did writings such as those in the I Ching and philosophies like Confucianism influence women’s roles in Chinese society?

- What were some benefits for women and their families if they became a Buddhist nun?

- How were women’s roles dictated by their social status in Song Dynasty China? Provide an example for women’s roles in the upper, middle, and lower classes of society.

- What is foot binding and how was this used as an indicator of social status in Song Dynasty China?

- Why do we know more about elite women than we do about those in the lower classes such as those who farmed?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- Earlier in this lesson, you read an article about Christianity’s impact on women in Europe. Using the communities frame, what are some general comparisons you can make about the impact of belief systems on women’s roles in society?

Du Huan (Graphic Biography)

Preparation

Summary

This biography tells the story of Du Huan, a Chinese soldier who was captured at the battle of Talas/Talus in 751 CE against Turkish rebels and Abbasid soldiers. He worked for his captors on a journey to East Africa. His description of the people he encountered is one of only a few written accounts about everyday people in this region that we have for this era.

Purpose

In this era, we highlight the networks that connected different societies across Afro-Eurasia and ask if this period really was a Dark Age. Du Huan’s story provides evidence to help you understand how people in different regions and communities were connected to and interacted with each other. These connections will help you challenge the narrative of a dark age in the centuries after the fall of the Roman and Han empires.

Process

Read 1: Observe

As you read this graphic biography for the first time, review the Read 1: Observe section of your Three Close Reads for Graphic Bios Tool. Be sure to record one question in the thought bubble on the top-right. You don’t need to write anything else down. However, if you’d like to record your observations, feel free to do so on scrap paper.

Read 2: Understand

On the tool, summarize the main idea of the comic and provide two pieces of evidence that helped you understand the creator’s main idea. You can do this only in writing or you can get creative with some art. Some of the evidence you find may come in the form of text (words). But other evidence will come in the form of art (images). You should read the text looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the main idea, and key supporting details. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Where was Du Huan born and how did he end up fighting in the battle of Talas/Talus?

- What happened to Da Huan and other captives after the battle? Why was his fate different from that of his friends?

- How does he describe production and distribution in Laobosa (probably Somalia)?

- How does he describe Molin, the province of Aksum he visited?

- How does the artist use art and design to give a sense of connection between these different places?

Read 3: Connect

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in this unit of the course. On the bottom of the tool, record what you learned about this person’s life and how it relates to what you’re learning.

- How does this biography of Du Huan support, extend, or challenge what you have learned about production and distribution in this era?

- How does this biography of Du Huan support, extend, or challenge what you have learned about networks and connections between regions in this era?

To Be Continued…

On the second page of the tool, your teacher might ask you to extend the graphic biography to a second page. This is where you can draw and write what you think might come next. Here, you can become a co-creator of this graphic biography!

Geography – Era 4 Mapping Part 2

Preparation

Purpose

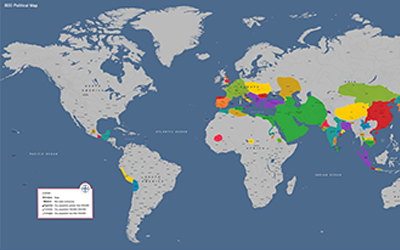

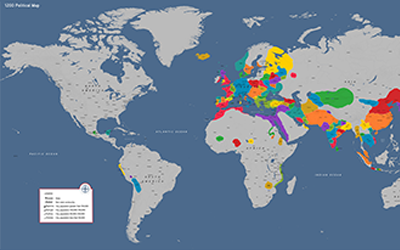

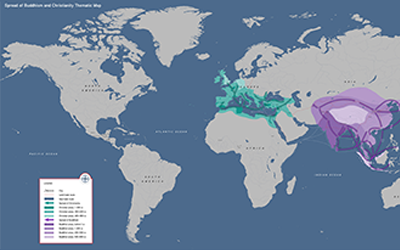

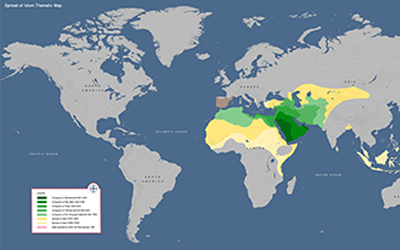

This activity will provide additional evidence to help you respond to the Era Problem: How did networks of exchange connect societies, and how were communities changed by these connections? You will reflect on what you’ve learned during this unit by comparing three political maps. You’ll also review the predictions you made about the consequences of long-distance trade in the Unit 2 Part 1 map activity earlier in this unit. Finally, you’ll be able to look at maps showing the spread of Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism as you discuss how societies restructure after collapse.

Process

This activity begins with an identification opening in which you identify seven political communities in the year 800 CE. Next, you will compare the maps of political communities in 100, 800, and 1200 CE as you evaluate how communities changed and stayed the same during this era. Finally, you will compare your guesses and predictions from the Part 1 activity and write a response to a prompt about collapse and restructuring.

Step 1

Identify the political communities associated with the numbers on the black-and-white map of the world in 800 CE and record your answers on the worksheet. You should complete this part of the activity without referencing outside sources or the rest of the maps in this activity.

Step 2

Open and review the 800 CE Political Map and correct your identifications. Then, in small groups, examine the 100 CE Political Map, the 800 CE Political Map, and the 1200 CE Political Map. You should compare these three maps and identify significant changes or continuities, focusing particularly on the collapse and restructuring of large states and empires.

Step 3

Remaining in small groups, open and review the Spread of Buddhism and Christianity Thematic Map and the Spread of Islam Thematic Map. Review the guesses and predictions you made in the Part 1 map activity for this unit. What did you get right? What did you miss? Finally, prepare a short paragraph or bullet list in response to this prompt:

At the beginning of this era, some of history’s most prominent empires collapsed, but soon, societies began to restructure. Yet, as you learned, this process of collapse and restructuring continued through this era. Using the maps you encountered in this era, explain the role of trade and the spread of religion in the patterns of collapse and restructuring you’ve seen in this unit.

Writing – Organization and Language and Style

Preparation

Purpose

As we continue the progression on writing, you will look at the elements of organization and language and style to ensure you have a solid grasp on each of these essentials of good writing. You will analyze another student essay to both identify and improve upon these aspects of the essay, helping to make sure you improving your historical writing skills.

Process

It’s time for another writing activity! By now, you’re probably getting familiar with these. In this one, you’re going to examine another student essay this time against the WHP Writing Rubric criteria for organization and language and style. The essay was written in response to the Era 3 DBQ, “Compare the philosophies of early imperial China (Legalism, Daoism, Confucianism, Buddhism) regarding how a state should be ruled.” You might recognize this if you completed the Era 3 DBQ.

Before starting your analysis, take a look at the WHP Writing Rubric and review the Organization and Language and Style rows of the rubric with your class.

Once you’ve reviewed these criteria, your teacher will probably put you into pairs or small groups to work collaboratively on the Writing – Organization and Language and Style worksheet. First, work with your group to identify the major claim in the essay. While the thesis is not the focus of this activity, as always, it’s difficult to assess the rest of the essay without being aware of the major claim, since everything in the essay should be tied to that claim.

Next, review the essay, first paying close attention to important elements of language and style. Underline any elements of language and style that could be improved upon. Then, suggest improvements for two of the issues you’ve identified. Next, look at the organization of the essay and highlight any areas where organization could be improved. For example, if there are any missing transitions, highlight this issue as an area that could be improved upon. Next, provide suggested improvements to two of the issues you’ve found with the essay’s organization. Finally, provide a score (advanced, proficient, developing, or emerging) and comments for each of these rows of the rubric. Be prepared to share your answers with your class!

Organization Warm-Up

Preparation

Carefully read the DBQ prompt you will be responding to. Be sure to have read and analyzed the documents prior to doing this warm-up activity.

Make sure you have drafted the thesis/major claim you intend to use in response to the essay prompt.

Purpose

This warm-up focuses on the Organization row of the WHP Writing Rubric and allows you to refine the way you structure your writing to most effectively support your argument and ideas. You will practice skills to use organization strategies and transitions to support your analysis and establish clear, meaningful connections between ideas. These writing skills are essential not just to essay-writing in all your classes, but are applicable to academic, professional, and personal writing at all levels.

Process

In this warm-up activity, you will learn how to organize your essays to help you create a paper that’s easy for your reader to understand. First, you’ll review the Organization row of the rubric, and then, you’ll work through a three-step process that will help you think about how you’ll organize your essay.

First, take out the WHP Writing Rubric and review the Organization row with your class. Discuss what you think organization is in this context and why it’s important to consider when writing essays. Remember, all arguments should have three components that make up the basic organization: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Within those components, writers make choices about the best way to order and present their ideas. Some writers use categories to structure their paragraphs (for example, economic, social, etc.) Others lay out their points in order of importance or move from most general to most specific. When we discuss organization in the context of the rubric, we’re really talking about the existence and effectiveness of the introduction and conclusion, along with the order in which ideas are presented within the body.

Additionally, a well-organized essay provides the reader with a roadmap, which should help them follow your argument more easily. So, how do you organize a paper? Well, there is a tool for that!

Take out the Organization Prewriting Tool and work through it according to your teacher’s instructions.

First, add the thesis/major claim to the top of the tool. Then, for Step 1, come up with three claims—or reasons—that support the thesis/major claim statement you just wrote. Then, for Step 2, use transition words to help you write your introduction and organize your body paragraphs.

Now you’re ready for Step 3, your conclusion. First, choose a transition word that will help you start your concluding paragraph. Then, summarize your supporting claims and their significance, describe why your argument is important, and then restate your thesis/major claim. The work you complete in Step 3 will help you write your concluding paragraph later.

Once you’ve completed the steps, it’s time to write!

DBQ 4

Preparation

DBQ Prompt: Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which the collapse of the Roman Empire and Han Dynasty China impacted trade networks up to c. 1200 CE.

Have the Comparison, CCOT, and Causation tools available (find all resources on the Student Resources page)

Purpose

This DBQ is another opportunity to get a sense of your progress in developing your historical thinking and writing skills. Additionally, writing DBQs will help prepare you to be successful on the written portion of standardized tests.

Practices

Continuity and change over time, contextualization, sourcing, reading, writing

All DBQs require you to contextualize, source documents, and of course as part of this, read and write. This particular DBQ asks you to evaluate how trade networks changed and stayed the same after the collapse of the Roman Empire and Han Dynasty.

Process

Day 1

It’s time for another DBQ. This time, you’ll be thinking about trade networks after the fall of the Roman Empire and Han Dynasty. The DBQ prompt is: Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which the collapse of the Roman Empire and Han Dynasty China impacted trade networks up to c. 1200 CE. Start out by using the Question Parsing Tool to help you figure out what this question is really asking, so you can write an appropriate response.

Take out the Era 4 DBQ and skim the documents quickly. Then, pick the thinking tool you want to use to help you analyze the documents (comparison, causation, or CCOT). Once you’ve picked a tool, read each document a bit more closely and write down or underline the information you think you might use in your essay, along with any additional sourcing you have time for. Write your ideas on your chosen tool as you work through the documents.

Next, create a major claim or thesis statement that responds to the prompt. The notes you have taken should help you form a defensible thesis statement.

Finally, it’s time to contextualize. As you likely know, all historical essays require this. If needed, you can use the Contextualization Tool to help you decide what to include.

Day 2

This second day is your writing day. Feel free to use your tools and notes from any prewriting work you completed as you craft your essay response. Make sure you have a copy of the WHP Writing Rubric available to remind you of what is important to include in your essay. And don’t forget to contextualize: Think of the entire time period, not just the time immediately preceding the historical event or process you are writing about. Your teacher will give you a time limit for completing your five- to six-paragraph essay responding to the DBQ.

DBQ Writing Samples

Preparation

Purpose

In order to improve your writing skills, it is important to read examples—both good and bad—written by other people. Reviewing writing samples will help you develop and practice your own skills in order to better understand what makes for a strong essay.

Process

Your teacher will provide sample essays for this era’s DBQ prompt and provide instructions for how you will use them to refine your writing skills. Whether you’re working with a high-level example or improving on a not-so-great essay, we recommend having the WHP Writing Rubric on hand to help better understand how you can improve your own writing. As you work to identify and improve upon aspects of a sample essay, you’ll also be developing your own historical writing skills!

Organization Revision

Preparation

Have your graded essay ready to use for annotation and revision purposes.

Purpose

When you take the opportunity to revisit and revise your writing, you are building editing skills that will serve you in all types of academic and professional writing. While the ‘revision’ stage of essay-writing is often the most dreaded (or, let’s be honest, sometimes skipped over entirely) part of the process, editing using targeted feedback is how you raise the level of your writing. This activity focuses on the Organization row of the WHP rubric and helps you identify areas of success and areas for improvement in your essays. You’ll use these fine-tuning structure and transition skills for writing in class and in life.

Process

In this activity, you’ll first review the Organization row of the WHP Writing Rubric with your class if you haven’t already done so. Then, you’ll review the Organization Revision Tool and learn how to use it to improve upon the essay’s overall clarity and organization. Finally, you’ll use the Organization Revision Tool to review and revise an essay.

If needed, start by reviewing the Organization row of the WHP Writing Rubric with your class. Discuss why it’s important to think carefully about how an essay is structured. Also, keep in mind that a well-organized essay always has an intro, a body, and a conclusion.

Next, take out the Organization Revision Tool and walk through it with your class. First, note the directions at the top, which ask you to review the feedback from an essay. This is a helpful step because it gives you a general sense of how the essay fared in terms of overall organization and clarity and where improvement is needed.

Now, it’s time to go through each item on the checklist to make sure all criteria related to organization were included in the essay. Work through the list with your class and be sure to ask questions if you aren’t clear about what an item is asking for. Remember, only check the boxes if the criteria are met. If any criteria from the checklist were not met, leave those boxes blank. The final step is to revise the essay based on all the blank checkboxes. Use the unchecked boxes as guidance for what can be done to improve the organization of the essay. You can also use the Organization Prewriting Tool to help structure revisions.

Once you feel like you have mastered how the Organization Revision Tool works, your teacher may have you work on another essay to practice your skills.