5.2 Old World Webs

-

11 Activities

-

10 Articles

-

6 Videos

-

1 Vocab Activity

Update ahead! This course will be updated soon. See what's changing.

Introduction

You’re about to learn a lot about the new world webs that were established after Columbus stumbled upon the Americas—in the lesson after this one. First, we need to note that the Americas already had plenty of networks of exchange that had taken centuries to develop, thanks to the Aztec, Incas, and other societies. Meanwhile, trade routes in Eurasia were spreading a plague so deadly it killed a third of the people there, dramatically altering most aspects of life. Understanding communicable diseases is essential when studying any far-reaching network of exchange, whether it’s Afro-Eurasia’s diverse “archipelago” of trade or the 25,000 miles of road laid down by the Incas in order to distribute what they produced.

Learning Objectives

- Understand and evaluate the regional networks of exchange that existed in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas during this era.

- Use graphic biographies as microhistories to support, extend, or challenge the overarching narratives from this time period.

- Learn about the causes and consequences of the Black Death and evaluate how this disease impacted human communities and networks.

- Learn about the Aztec and Inca empires.

- Analyze primary sources to understand contemporary reactions to the Black Death.

Making Claims – Pastoral Empires

Preparation

Purpose

This activity asks you to practice your claim- and counterclaim-making skills. This will help you evaluate your ability to make strong, evidence-backed claims, and give you an idea of how well you understand the key features of pastoral empires.

Process

In this activity, you’ll write two claims and one counterclaim about pastoral empires.

Take out the Making Claims – Pastoral Empires worksheet. Working individually or in pairs, make two claims and one counterclaim about whether the label pastoral empire is accurate for the Mongols and Comanches. It may help to review the traditional definition of an empire.

For each claim, use course materials—and, if your teacher asks you to, the Internet—to find two pieces of supporting evidence. Once you’ve written your two claims and provided supporting evidence, write one counterclaim that relates to one of them. You should also provide two pieces of evidence to back up your counterclaim.

Be prepared to share your claims at the end of the class.

Archipelago of Trade

Vocab Terms:

- brocade

- cavalry

- formidable

- hegemony

- luxury item

- maritime

- rapacious

Preparation

Summary

The Afro-Eurasian trade system of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was the largest integrated commercial network in the world at the time. It helped with the exchange of products, people, knowledge, technologies—and germs. There wasn’t one dominant society controlling this trade, and many smaller networks linked up into a massive network. Over time, however, Europeans gained more and more power over global trade.

Purpose

This article will give you information about different trade centers across Afro-Eurasia in the thirteenth and early fourteenth century, at the beginning of this era. This is before their collapse due to the Black Death, their recovery, and then the Columbian Exchange that began in the 1490s. This information will help you respond to the Era 5 Problem, which asks how the first global system changed things. It will give you evidence from before the beginning of that system.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Why is the Afro-Eurasian system of long-distance trade described as an archipelago?

- What was the effect of the Mongol Empire on trade?

- What role did this regional trade network play in helping Johannes Gutenberg create his printing press?

- What impact did annual fairs have on the European economy?

- What was one negative effect of interconnected trade?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- This article is about production and distribution in Afro-Eurasia. Which Afro-Eurasians does it leave out? Whose experiences of production and distribution are not included in the article?

- How did European production and distribution change over time? How did these regional changes affect global production and distribution? Use evidence from this article and other articles and videos in this lesson to make and defend a claim in response to this question.

Guilds, Wool, and Trade: Medieval England in a Global Economy

Summary

We might think of the Afro-Eurasian trading system as an archipelago of trade—a chain of overlapping trade circuits and trading cities. In the thirteenth century, England was at the far end of this archipelago of trade. England’s most valuable trade good was wool, which it exported to Western Europe and the Mediterranean. The best wool in Europe came from England, and England’s economy ran on wool. The wool trade helped empower an English merchant class. By the fourteenth century, these merchants organized into a guild that gave them more power and privileges in English society.

Guilds, Wool, and Trade: Medieval England in a Global Economy (9:29)

Key Ideas

Purpose

The Era 5 problem asks you to consider how increasing connections promoted change globally and regionally. England may have been at the far corner of Eurasia in the thirteenth and fourteenth century, but the wool trade made England a key part of regional trade. By the end of Era 5, England emerged as a much more central part of the global economy. This video provides you evidence at the local and national level to respond to the era problem. As you watch, evaluate the impacts of the wool trade on England’s history and its growing interconnections with the rest of the world.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- How do Nick and Trevor describe the Afro-Eurasian trade system in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries?

- Why did people in Flanders and northern Italy buy English wool?

- Who produced wool in England?

- How did the wool trade empower the merchant classes? What role did guilds play in this process?

- Why was wool important for England?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- English wool is one example of a local good that was traded across extensive regional networks. The trade reshaped both communities and networks in England and across Western Europe. Can you think of anything that is or was once made in your community? Where does that good get distributed? Who produces it? How does that industry affect your community, and how do you think it impacts other places?

- How would you tell the story of the Worshipful Company of Woolmen differently in each of the three course frames? How were they a community? How did they shape networks? What impacts did they have on production and distribution in England and the larger region?

Silk and the Song Dynasty

Summary

Silk: more than just nice for clothing, it funded the rise of Song Dynasty China and was the lynchpin of the largest trading system of the medieval world. English wool and Indian cotton, while important as trade goods across pre-Mongol Eurasia, couldn’t compete. Silk was used for intricate art, as the currency that paid large armies, and as the symbol of imperial power. With the help of Dr. Xiaolin Duan, we explore both the myths, and the history, that made Song Dynasty China a silk powerhouse.

Silk and the Song Dynasty (12:27)

Key Ideas

Purpose

Silk helped make Song Dynasty China not only a powerful manufacturing state, but also a big part of the trading networks connecting Afro-Eurasia. As you watch the video, consider how silk affected both Chinese state and society and also production and distribution and networks of exchange. This video will provide you with evidence to help you answer the Era Problem. You may want to compare and link this narrative to the story of wool in England told in Guilds, Wool, and Trade: Medieval England in a Global Economy.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- According to Francesca, where was silk produced in the era of the Song Dynasty, and what were some of the most important export markets?

- According to Professor Xiaolin Duan, how did the economy work during the Song Dynasty? Who made silk, in particular?

- Other than clothing, what other uses were there for silk?

- According to Professor Duan, was the silk trade part of a wider Afro-Eurasian trading system? How?

- What does the Pictures of Tilling and Weaving tell us about who did most of the work to produce silk?

- Does Professor Duan believe that there was an industrial revolution in China in this period? What evidence is there for it?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- Chinese silk is one example of a local commodity that was traded across extensive regional networks. The silk trade reshaped both communities and networks in China and across much of Asia. Can you think of anything that is or was once made in your community? Where does that good get distributed? Who produces it? How does that industry affect your community, and how do you think it impacts other places?

- How would you tell the story of silk differently in each of the three course frames—community, networks, and production and distribution?

Zheng He (Graphic Biography)

Preparation

Summary

Zheng He is “world history” famous as the admiral whose voyages from China to Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and even East Africa, demonstrate a thriving Indian Ocean world before the coming of Europeans. Usually, his massive fleets are depicted as largely peaceful trading voyages. Some scholars, however, argue that they were violent acts of Ming Dynasty empire-building. His biography helps us understand why this debate is important.

Purpose

We learn about Zheng He because we are studying connections and networks among countries and people in this era, which were quite extensive. Zheng He’s expeditions may have been the largest organized missions of this era, and they crossed long distances. Thus, we get a sense of just how connected large parts of the Afro-Eurasian world were in this era. However, how should we describe these connections? What did they mean? How did they work? This biography helps raise (and maybe answer) some important questions about these voyages.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did Zheng He come to have three names?

- What did Zheng He do as the admiral of the Ming Dynasty?

- How does Xu Zu-Yuan describe these journeys, and how does this contrast to later Portuguese expeditions in this region?

- How does Geoff Wade describe these journeys, and what is his evidence?

- How does the artist use art and design to contrast and illustrate the two big theories about Zheng He’s voyages?

Evaluating and Corroborating

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in the course.

- How does this biography of Zheng He support, extend, or challenge what you have learned about connections across Afro-Eurasia in this period?

New World Networks: 1200-1490s

Vocab Terms:

- empire

- exchange

- indigenous

- irrigation

- tribute

Preparation

Summary

Indigenous American networks of exchange came in many different shapes and sizes, from complex, imperial systems of communication to smaller, local networks. Some networks moved massive amounts of people, goods, and ideas, like the Aztec and Inca networks.

Purpose

This article provides an overview of networks of exchange across the Americas in the era prior to the Columbian Exchange. You will be able to compare and contrast these networks to others in Eurasia during this period, and also, later, to the systems in place in the Americas after the Columbian Exchange begins. This will help you to respond to the Era Problem: How did the first ongoing global connections among the hemispheres promote change both globally and regionally?

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Where were most of North America’s networks of exchange located? Why?

- What was significant about Aztec marketplaces?

- How was the Aztec Empire maintained?

- What challenges did the Inca Empire face when trying to unify? How did they overcome it?

- What was the mita (Mit’a) system?

- What was unusual about Inca trade?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- At this time, we have less information about networks in the Americas prior to the sixteenth century than we do for much of Afro-Eurasia. Based on this article, compare and contrast networks in the Americas to those you have already learned about in Afro-Eurasia. Can you identify what information about networks in the Americas would help you to complete this comparison?

Pre-colonial Caribbean

Summary

Migrations from the Central and South American mainland to the Caribbean islands began c. 5000 BCE. Over the course of thousands of years, indigenous peoples created communities and established networks of exchange between islands and with the mainland. Trade goods such as jade, ceramics, shells, and teeth moved across aquatic highways. However, these highways would change dramatically after 1492 with the arrival of the Spanish and the sustained connections between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres.

Pre-Colonial Caribbean (12:07)

Key Ideas

Purpose

This video provides information about pre-colonial Caribbean communities and networks that are often overlooked in textbooks. You will use the evidence presented here to support, extend, and challenge the networks frame narrative. This video will also provide you with evidence to assess networks that existed before the Columbian Exchange. This evidence will help you identify changes that took place post-1492 and respond to the Era Problem.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Before you watch the video, open and skim the transcript. Additionally, you should always read the questions below before you watch the video (a good habit to use in reading, too!). These pre-viewing strategies will help you know what to look and listen for as you watch the video. If there is time, your teacher may have you watch the video one time without stopping, and then give you time to watch again to pause and find the answers.

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- What were the two major moments of migrations to the Caribbean islands and when did these take place?

- Dr. Hofman states that the soil has to be opened like a book in order to learn about these early Caribbean peoples. What types of information can archaeologists learn by doing this?

- What were belief systems like in the early period of migration? How did these beliefs change in the later periods?

- How do we know that there were continued contacts and exchanges between islands and between the Caribbean islands and the mainland of Central and South America in the pre-colonial period?

- How did the indigenous Caribbean peoples help the Spanish and what occurred as a result of this help?

- Who were the Kalinago and where did they settle?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- In the video, Dr. Hofman states that 1492 marks “the beginning of the true globalizing world.” What evidence does she give to support this statement, and do you agree with her? Explain your reasoning.

- How does the history of the pre-colonial Caribbean support, extend, or challenge what you’ve learned about networks and communities in this unit?

Aztec Empire

Vocab Terms:

- autonomous

- city-state

- civilization

- colonization

- colony

- conquistador

- tribute

Summary

The Aztec Empire emerged from a bunch of Aztec city-states. One of these city-states, Tenochtitlan, was kind of an underdog. But in the context of a civil war, it formed a strategic alliance with other city-states to form the famous Aztec Empire—with Tenochtitlan as its seat. For a while, this system worked. But when the empire was invaded from outside, the city-state system could not hold the empire together.

Aztec Empire (5:13)

Key Ideas

Purpose

By describing the context of the formation and decline of the Aztec Empire, this video will provide evidence for understanding the Americas prior to the Columbian Exchange. Later, you will look at how things changed after 1492. This will serve as evidence for responding to the Era Problem: How did the first ongoing global connections among the hemispheres promote change both globally and regionally? The evidence this article provides will also help you evaluate whether the communities frame narrative is accurate for this period.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- What did Aztec society have in common with ancient Greece?

- What was the Triple Alliance, and in what context did it develop?

- How did the system of city-states help Hernando Cortes conquer the Aztec Empire?

- The author of the video describes the Aztec Empire as advanced. What evidence does the author give for this claim and is the author’s argument convincing?

- How did Aztec political communities differ from Maya political communities?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- How does the Aztec state compare or contrast to different types of states and communities you have learned about in Afro-Eurasia?

Macuilxochitl (Graphic Biography)

Preparation

Summary

Macuilxochitl was a Mexica (Aztec) poetess. Her life and her poetry are evidence of the structure of the Aztec state and the networks built by the Mexica people and their neighbors prior to the Columbian Exchange.

Purpose

The Americas often seem less familiar and easy to grasp than Afro-Eurasia in the pre-Columbian period. But we know quite a bit about how some states, especially the Aztec state, actually worked. Tribute played a central role in both the economy and the governing of the state. One of our sources for understanding the Aztec state is the poetry of Macuilxochitl, in particular the poem about the emperor Axayacatl. Use this source to help you to build your understanding of networks and communities in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

Process

Preview—Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas—Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. You should also spend some time looking at the images and the way in which the page is designed. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- Who was Macuilxochitl and how does she describe herself?

- She describes the Tenochtitlan (Aztec) conquest of Tlacotepec as “forays for flowers [and] butterflies.” What does this mean?

- She writes that Axayacatl spared the Otomi warrior partly because he brought a piece of wood and deerskin to the ruler? What does this tell you?

- How does the artist use art and design emphasize and demonstrate the importance of tribute?

Evaluating and Corroborating

In this read, you should use the graphic biography as evidence to support, extend, or challenge claims made in the course.

- How does this biography of Macuilxochitl support, extend, or challenge what you have learned about the state and economy in Mesoamerica in this period?

Inca Empire

Vocab Terms:

- civilization

- conquest

- conquistador

- empire

- labor

- tribute

Summary

The Inca Empire started off as the Kingdom of Cusco. Under the leader Pachacuti, the Inca brought other groups under their control and under their collected tribute system called the mita (Mit’a) system. This system helped the Inca build its famous monuments and grow into a sophisticated empire with ten million residents.

Inca Empire (4:35)

Key Ideas

Purpose

By describing the formation and operation of the Inca Empire, this video provides evidence for understanding the Americas prior to the Columbian Exchange. Later, you will look at how things changed after 1492, which will serve as evidence for responding to the Era Problem: How did the first ongoing global connections among the hemispheres promote change both globally and regionally? The evidence this article provides will also help you evaluate whether the communities frame narrative is accurate for this period.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- Who was Pachacuti?

- What did the Inca call themselves? What did Inca mean?

- What made the Inca an empire?

- How many people were living in the Inca Empire prior to its decline?

- What was the Mit’a system?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- How does the Mit’a system compare or contrast to systems of production and distribution in Afro-Eurasia during this era?

Traveler Postcards

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, you will read travel accounts from thirteenth- and fourteenth-century missionaries and merchants, and then write a postcard from the perspective of one of them. This will help you practice the skill of avoiding presentism and having historical empathy. Furthermore, reviewing these travel accounts will help you better understand the networks of production and distribution at this time, and the communities that gathered around them.

Practices

Sourcing

To gain a solid understanding and realistic perspective of each traveler, you will have to source the travel accounts documents, identifying the intention and purpose of each account.

Process

In this activity, you are going to read some primary source excerpts about travelers from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Then, you will create a postcard from one of these travelers to someone back home, describing their travel experiences. You will be asked to share your postcard with the class.

There are six travelers included in “Travelers’ Accounts Excerpts.” Your teacher will assign you a traveler from this list:

- Francesco Balducci Pegolotti, a Florentine merchant

- Friar Odoric, also known as Odoric of Pordenone, a Franciscan friar and missionary explorer

- Rabban Sawma and Rabban Markos, Nestorian monks (Note: You can write the postcard from the perspective of one or the other or both.)

- Marjory Kempe, an English Christian mystic and traveler

- Ibn Battuta, a Moroccan scholar and explorer

- Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant

Once you know which traveler you will learn more about, use the Sourcing – HAPPY Tool to unpack your traveler’s account. Once you have done that, create a postcard using the template. On the left side of the postcard, draw an image that shows what the traveler saw or experienced. On the right side of the postcard write a letter home that explains the following:

- Where they traveled.

- What they have seen, for example, new religions, new trade items, new cities, and so on.

- Any new knowledge or items they acquired.

- How they impacted the cities they visited.

Once you are done with your postcard, be prepared to share yours with your class. Since there will be multiple postcards from the same people, make sure to compare the similarities and differences and discuss how you and your classmates might have interpreted the same accounts differently. Remember that in using primary source documents and interpreting history, it’s not at all unusual to come up with different interpretations of the same thing! This is one of the reasons history is interesting and also sometimes difficult to interpret and use!

Contagion!

Preparation

Purpose

You will play a trading game in this activity that will help you learn about some specific events that occurred during this era, which will help make this topic more concrete.

Practices

Causation

You will be asked to model the spread of disease and pandemics, which in many ways creates a causal map of how disease travels and its effects.

Process

In this activity, you will first play a card trading game, and you will then be asked to create an infographic that relates to the game’s outcome.

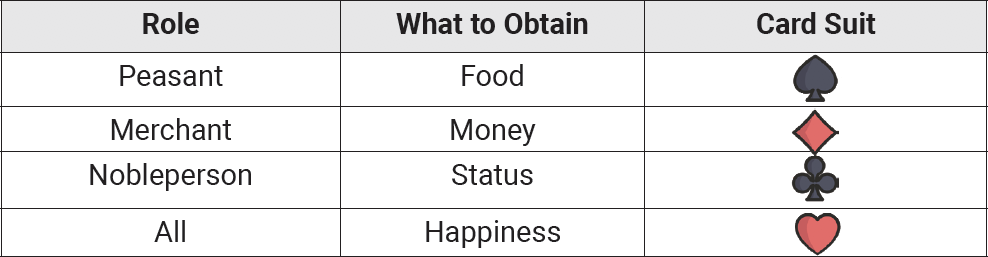

Part 1

As you come into the room, your teacher will hand you a 5x7 card that will tell you if you are going to play the role of a peasant, a merchant, or a nobleman or woman in this game. Then, your teacher will give you each some playing cards. The goal of the game is to gather more of one card suit than anyone else. The suit you must collect depends on the role you’re playing. Each card is worth one point. Here is the key to determining which suit each role should collect:

You can decide how you want to make trades. There is only one rule to the game: Every time you trade with someone, you have to write that person’s name down on your 5x7 card.

Once everyone has their cards and is ready, you will have 5 minutes to trade. Your teacher will tell you when the time is up, and will explain what to do next.

Part 2

Now that you know the game is actually about pandemics and not just trading, you are going to think about how dangerous pandemics really are to humanity. There are some scientists, such as Amesh Adalja from Johns Hopkins University, who believe that pandemics are one of the greatest threats to our species. They think pandemics are more likely to destroy humanity than the impacts of climate change and natural disasters, more than the threat of nuclear war, or even cyberwar. It is your job to do some research on the history and spread of pandemics and to create an infographic that displays this history. Then, you’ll decide if you agree that pandemics are the greatest threat to humanity.

Get into small groups to start working on your infographic. Note that your infographics must include information about at least four pandemics, and one of those them must be the Black Death. The infographic should also include information about the causal relationships between the pandemics and the WHP frames of communities, networks, and production and distribution. More specifically, show how pandemics may have impacted the community, networks, and production and distribution frames, and conversely, how those frames impacted the spread of pandemics.

As you create your infographic, pay attention to the following:

- Topic – Make sure the topic—pandemics—is somehow defined or explained through visuals.

- Type – The type of infographic chosen (for example, timeline or informational) should strongly support the content being presented.

- Objects – The objects included in the infographic should be relevant and support the topic.

- Data visualizations – The data visualizations must present accurate data and be easy to understand.

- Style – Fonts, colors, and organization should be aesthetically pleasing, appropriate to the content, and enhance the viewer’s understanding of the information presented.

- Citations – Full citations for all sources must be included.

Take some time to research some past pandemics and gather the information for your infographic. Once you’ve designed and constructed your infographic, be prepared to display it. You and your classmates will take part in a gallery walk so you can get more familiar with the information shared on each. As you view each of the infographics, write down three pieces of evidence that either support or challenge the argument that a pandemic is the greatest threat to our society today. You’ll either share your findings with the class or hand them to your teacher.

Trade Networks and the Black Death

Vocab Terms:

- conquest

- epidemic

- feudalism

- network

Preparation

Summary

This is an article about unintended consequences. It traces the spread of the Black Death, also called the Bubonic Plague, across the same networks that moved ideas and trade goods. With increasing connections, merchants and the animals that accompanied them—sometimes without their knowledge—came in contact with more and more people. That in turn helped disease spread, devastating many communities in Europe, Asia, and North Africa.

Purpose

This article focuses on how networks facilitated the spread of a disease, which in turn had a massive impact on production and distribution. It provides evidence that will equip you to evaluate both of these frame narratives for this era.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did the success of the Mongol state help the Black Death spread?

- How many people are estimated to have died from the plague?

- What do gerbils have to do with plague?

- Where was plague the worst? Why?

- How did the plague affect economies?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following questions:

- In the production and distribution narrative, we generally hear about expanded trade routes as a purely good thing. How does this article affect that view?

- We have previously studied the ideas of collapse, recovery, and restructuring. Would you call the results of the Black Death collapse? What collapsed? What didn’t? What kind of recovery would you expect to see in different regions of Afro-Eurasia?

Quick Sourcing – The Black Death

Preparation

3x5 note cards or cut up paper

Purpose

This sourcing collection, along with the Quick-Sourcing Tool, gives you an opportunity to practice a quicker kind of sourcing than you do in the sourcing practice progression. The tool and the process for using it—specifically designed for unpacking document collections—will help you be successful when responding to DBQs.

Process

Note: If you are unfamiliar with the Quick-Sourcing Tool or the process for using it, we recommend reviewing the Quick-Sourcing Introduction activity in Lesson 5.1.

The Quick-Sourcing Tool can be used any time you encounter a set of sources and are trying to respond to a prompt or question, as opposed to the deeper analysis you do when using the HAPPY tool that is part of the sourcing progression.

First, take out or download the sourcing collection and review the guiding question that appears on the first page. Then, take out or download the Quick-Sourcing Tool and review the directions. For Part 1, you’ll write a quick summary of each source in terms of how it relates to the guiding question (we recommend using one note card or scrap of paper for each source).

For Part 2, which uses the first four letters of the acronym from the HAPPY tool, you only have to respond to one of these four questions. You should always include the historical significance or “why” (the “Y” in “HAPPY”) for any of the four questions you choose to respond to.

In Part 3, you’ll gather the evidence you found in each document and add it to your note cards so you can include it in a response later. Once each document is analyzed, look at your note cards and try to categorize the cards. There might be a group of documents that support the claim you want to make in your response, and another group that will help you consider counterclaims, for example.

To wrap up, try to respond to the guiding question.

Source Collection – The Black Death

Vocab Terms:

- contemporary

- epidemic

- hypothesize

- infection

- physician

- symptom

Preparation

Summary

The Black Death devastated Afro-Eurasian communities in the fourteenth century, but the origins of the bubonic plague may have begun much earlier than previously thought. The sources in this collection range from firsthand accounts of the plague’s devastation in the fourteenth century to scholarly articles from the twenty-first century.

Purpose

The primary and secondary source excerpts in this collection will help you understand the origins and spread of the fourteenth-century Black Death and how our understanding of this epidemic has changed over time. In addition, you’ll work on your sourcing skills using the Quick-Sourcing Tool.

Process

We recommend using the accompanying Quick Sourcing activity (above) to help you analyze these sources.

The Renaissance

Preparation

Summary

Beginning in fourteenth-century Italy, a cultural movement of artists and scholars—mostly wealthy men—kicked off the European Renaissance. They sought to revive the arts, architecture, and literature of the ancient Greeks and Romans…At least, that’s the usual story we get. Arguably, however, the Renaissance was as much about linkages to other regions of Afro-Eurasia than it was about reviving an ancient European past. It wasn’t just European men who took part in this movement. Women, trade with the Islamic world and Africa, and global economic developments each played a significant role in shaping Renaissance art and thinking.

Purpose

The Renaissance is a hotly debated historical topic. Many states require your teachers to cover the Renaissance. Some scholars argue it was central to the development of the modern world. Others argue that it didn’t actually happen. This article provides you with evidence to support, extend, and challenge narratives about the Renaissance.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

Fill out the Skimming for Gist section of the Three Close Reads Worksheet as you complete your first close read. As a reminder, this should be a quick process!

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

For this reading, you should be looking for unfamiliar vocabulary words, the major claim and key supporting details, and analysis and evidence. By the end of the second close read, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- According to the author, what was the Renaissance?

- What did Renaissance thinkers and artists in Italy believe they were doing?

- According to the author, how did historians in the nineteenth century use the Renaissance to build narratives?

- How did different types of people experience the Renaissance?

- How did trade help start the Renaissance?

- How does the author use connections with the Islamic world to challenge the narrative that the Renaissance was all about reviving Greek and Roman culture?

- What does the author argue that the painting, “The King’s Fountain,” shows us about life in Renaissance Europe?

Evaluating and Corroborating

At the end of the third close read, respond to the following question:

- How does your interpretation of the Renaissance change if you explain it through each of the three course frames?

- How would you describe the Renaissance to somebody who knew nothing about it? Use evidence from the article to support, extend, or challenge the idea of a uniquely European cultural movement that started in fourteenth-century Italy.

Vocab – What’s My Word?

Preparation

Purpose

In this activity, you will be assigned a mystery vocab word, and your job is to go around the room and ask enough questions of your classmates to try to figure out what the word is. You’ll have to use your questioning and deduction skills to figure out the word. In many ways, you are being asked to take context clues to help you figure out your word. This is a great way to determine if you really understand the words from the era, or if you need more practice.

Process

You are going to play the vocab game, “What’s My Word?” And, it’s exactly as it sounds—you’re going to be assigned a vocab word, but you won’t know what it is. Your job is to ask your classmates questions about your word until you correctly guess what it is.

Your teacher will explain how the game works. Once everyone is ready, your teacher will place a vocab word, written on an index card, face down on your desk. DO NOT LOOK AT THE WORD. Instead, when your teacher says “go,” hold up the card to your forehead, with the word facing out, and then go around the room asking questions until you’ve figured out your word.

Once your whole class has figured out their words, think about and discuss the following questions with your class:

- What kinds of questions did you ask?

- What types of questions most easily led you to figure out your word?

- How might these types of questions help you figure out unfamiliar words that you encounter in the course?

Disease! Crash Course World History #203

Vocab Terms:

- anticlerical

- economics

- epidemic

- guild

- inoculation

- irrigation

- pandemic

Summary

Diseases have been around for all of human history. But in different times and places, the same microbes have had very different effects. Where diseases have spread rapidly, they have contributed to some world historical changes, like the decline of empires, reorganized labor systems, or colonization. The impact of disease leads us to question whether the humans are the authors of our story or whether other species are really the agents of change.

Disease! Crash Course World History #203 (11:36)

Key Ideas

Purpose

The Era 5 Problem asks: How did the first ongoing global connections among the hemispheres promote change both globally and regionally? Some logical responses to that question might start with the impact of diseases. This video introduces the topic of the impact of disease in human history to help prepare you to look at this era specifically.

Process

Preview – Skimming for Gist

As a reminder, open and skim the transcript, and read the questions before you watch the video.

Key Ideas – Understanding Content

Think about the following questions as you watch this video:

- How did migration and population density contribute to the historical rise and fall of disease rates?

- Why might hunters and gatherers have had fewer diseases than farmers or pastoralists?

- What made ancient Greece more susceptible to disease?

- What are some world historical effects of plague?

- Did the Black Death or the Great Dying have more fatalities? Why did one have much higher mortality rates?

- How did population density and disease contribute to European colonization in the Americas?

- Why do we have relatively lower disease rates now? Why are disease rates in danger of rising again?

Evaluating and Corroborating

- According to the author of the video, humans are not the only agents of history, meaning they’re not the only species to cause change. What other sources or facts that you have studied support, extend, or challenge the author’s argument?