Origins and Impacts of Nationalism

What exactly is nationalism?

It feels like we’ve always had countries. But in fact, nations are only a little more than 200 years old. If you think about how long people have been around and all the kinds of governments and kingdoms and empires they’ve built over thousands of years, nations are actually quite young!

We often think our nation is an important part of our identity—I am “American,” “Indian,” “Italian,” “Chinese,” and so on. But what does that really mean? How are you part of your nation? Indeed, what is a nation? Simply put, a nation is a group of people speaking a common language, sharing a common culture, a sense of a common destiny, and sharing a common history.

Nations and nationalism are linked together. What is nationalism? Well, it is a term to describe the common bonds that hold people together within a nation, creating a new type of community. Tied to this is the idea that individuals’ loyalty should be focused on the nation and that each nation should be able to determine its own future—an idea known as self-determination. So, nationalism is also the idea that the nation should have that right to govern itself and the right to self-determination. Finally, sometimes, nationalism is expressed in the belief that one’s own nation is better than other nations. In those instances, it can become competitive or discriminatory.

Nationalism bonds people together in a way that is not based on family ties, or even on having a personal connection with other members of your nation. In some ways, the idea of a nation is actually based on an imaginary relationship between the individual and all others in his or her country. Nations could be considered imagined communities because so much of the making of a nation is about creating unity and loyalty in our minds. It is not enough to just have a common government. To create and build the community of a nation, we also must have shared cultural symbols like flags and national anthems, and a shared idea of our national history.

Origins

As noted earlier, nationalism is not very old. Before the very end of the eighteenth century, nationalism didn’t even exist! When people told you where they were from, they said the name of a village or town. How did we go from identifying ourselves by our town to identifying ourselves by our nation? Well, to understand that we need to look at some of the revolutions around the turn of the nineteenth century, especially in Europe, and what people were fighting for, and against.

The French Revolutionary era had great importance in the development and spread of nationalism. After French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte rose to power in 1799, he extended the central government of France into all the countries he conquered across Europe. Traditional local powers were pushed aside.

The French people soon gained a sense of cohesion through their opposition to France’s many enemies. They were able to define themselves both as what they were—”We’re French”—and what they were not—not English, not German, not Italian, nor anything else. The military victories of France helped to create a common sense of history and identity, making nationalism strongest in France. But here’s the funny thing about nationalism: As Napoleon expanded and his armies took over many other European countries, those other countries all agreed national self-determination was the way to go. Uniting against the French rulers created a sense of common destiny—a sense of nationalism.

Napoleon ended up unintentionally leading Europeans from old regimes of kings, queens, and subjects to new nations of citizens and parliaments, but that’s not the only reason nationalism took hold. There were many other trends occurring at the same time, including the growth of large cities and a growth in literacy. Common bonds formed between intellectuals and the reading public within countries. The most devoted nationalists in the early nineteenth century were university students in cities. Peasants, who were mostly unable to read, were left out of the nationalism conversation until later.

Other reasons…

Some historians have argued that nationalism became important because older loyalties became less important— which brings us to religion. For hundreds of years after the split of the Christian church into Catholic and Protestant wings, people defined themselves in terms of their Catholicism or Protestantism and wars were fought over religious and dynastic loyalties. The Enlightenment weakened the hold of religion over many parts of the population by pointing out the abuses of the church and focusing on reason. People soon lost trust in religious authorities. In addition, Europe’s kings and queens began to lose popular support. Between the Enlightenment ideas and the French Revolution, there were enough critiques of monarchies to shift the people’s loyalties.

While nationalism has much to do with unity, its development often comes through the defining of differences. Russia in the nineteenth century is a great example. For Russians, nationalism wasn’t just about customs, language, and history, though those mattered. Russian nationalists defined themselves as not part of the West—Western Europe. The Western European models of industrialization and constitutional governments had no appeal to Russian nationalists, who wanted to keep their rural and religious traditions.

Across the Atlantic in the Americas, nationalism got going even earlier than in Europe. As Napoleon was taking over much of Continental Europe, Touissant L’Ouverture helped establish the second independent republic in the Americas in Haiti in 1804. After several hundred years of European colonization in the Americas, people had changed. There was less distinction between European colonizers and the local populations. Many people had closer ties to the colonized lands than to the European powers who controlled them. Local loyalty to the land where they lived would encourage national movements. These movements would become revolutions for national liberation and decolonization both during the nineteenth and through the mid-twentieth century.

Obstacles

France already had a central government and system of local administration that helped bring the center and outlying areas together. This state structure helped to build ideas of “the Nation.” But that wasn’t the case in many other countries. Sure, Germany and Italy each had common literary languages and the elites of these countries were developing ideas of a common destiny for all German or all Italian peoples. But neither place had a central government structure. They were both split up into a whole bunch of little states without any notion of German or Italian citizenship, no national armies, and their various royalty did not include a singular, that’s-the-one-in-charge monarch in either place. Nationalists in places like Italy and Germany had to do a lot more than just talk up the benefits of nationhood to the population. They also had to propose a way that the nation could be expressed in a form of government. It wouldn’t be until 1871 that these two regions would each become unified into nations. In Germany it would be through the military force of the Prussians and in Italy, through the political leadership of the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia in the northwest part of present-day Italy.

Conclusions and future differences

The rise and spread of nationalism gave people a new sense of identity and unity. It also led to increased competition among nation-states. After Napoleon was defeated, several other European nations joined together to attempt to return to the old—conservative—ways. As a result, royal dynasties returned to their thrones. However, over the following century several revolutions across Europe would remove these royals from power. New constitutional governments led by citizens of these nation-states would take their place. By the end of the nineteenth century, these nation-states were locked in a competition for colonies in Africa, Eastern Asia, and Southeast Asia. At the beginning of the twentieth century, nationalism played a major role in the extremely bloody competition between nations we now call World War I.

Malcolm F. Purinton

Malcolm F. Purinton is a part-time lecturer of World History and the History of Modern Europe at Northeastern University and Emmanuel College in Boston, MA. He specializes in Food and Environmental History through the lens of beer and alcohol.

Image credits

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0 except for the following:

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0 except for the following:

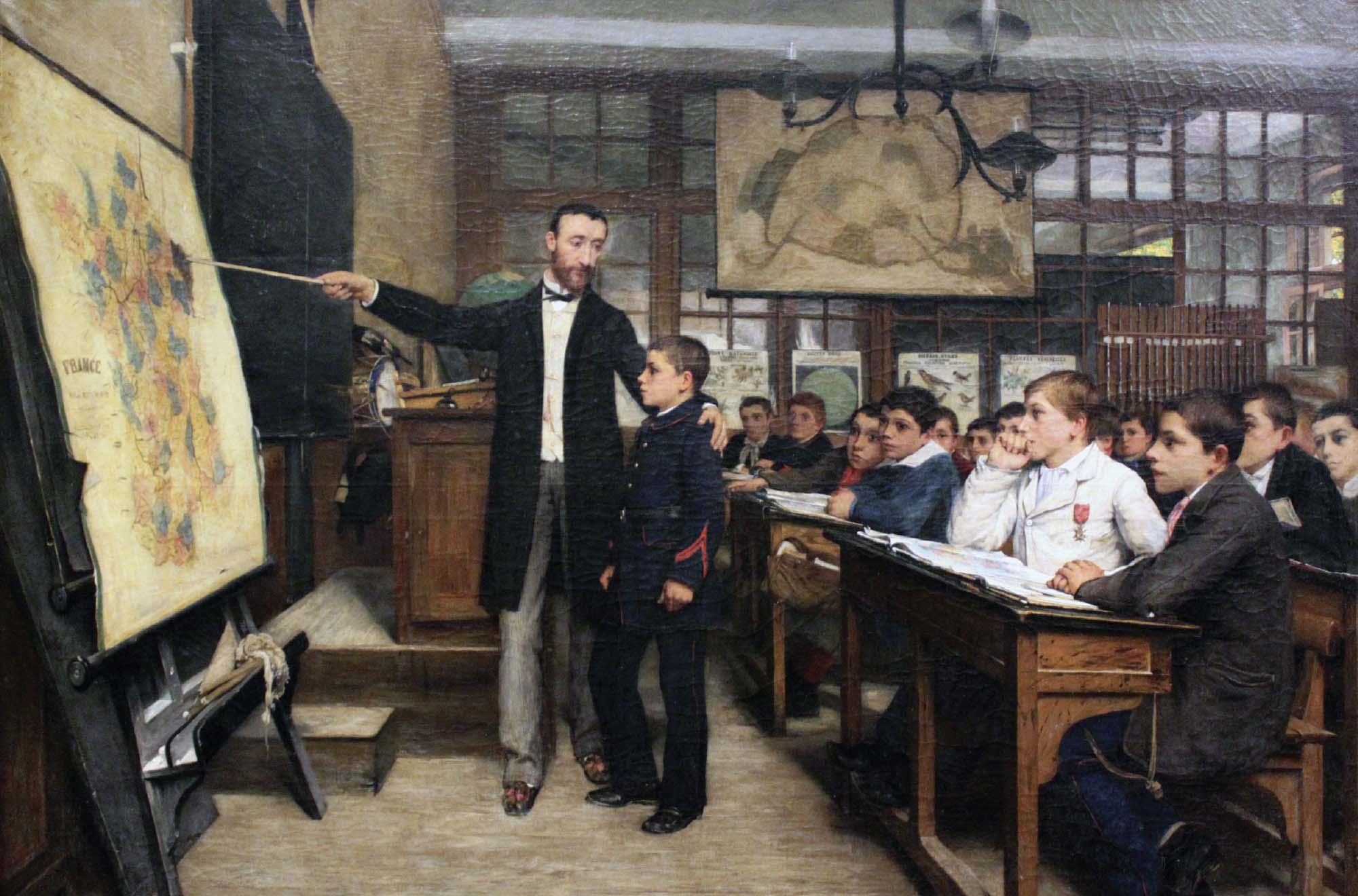

Cover: The Black Stain Alsace-Lorraine was the black stain of France. The ceding of the region to the German Empire in 1871 deeply hurt the French people. The desire for revenge in France was wide-spread. By Albert Bettannier, Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1887_Bettannier_Der_Schwarze_Fleck_anagoria.jpg

An elaborate satirical map reflecting the European nations in 1899. How are European nations represented? By Frederick W. Rose, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angling_in_Troubled_Waters_A_Serio-Comic_Map_of_Europe.jpg#/media/File:Angling_in_Troubled_Waters_A_Serio-Comic_Map_of_Europe.jpg

Napoléon Bonaparte in 1799 by François Bouchot, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Napol%C3%A9on_Bonaparte#/media/File:Bonaparte_in_the_18_brumaire.jpg

“St. Domingue: Prise De La Ravine Aux Couleuvres.” (Saint Domingue: Capture of Ravine-à-Couleuvres) Depiction of the Battle of Ravine-à-Couleuvres (23 February 1802), during the Haitian Revolution by Jean Jacques Outhwaite. Public domain. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Revolution#/media/File:Haitian_revolution.jpg

The German Empire is proclaimed in 1871, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Proclamation_of_the_Empire.jpg#/media/File:Proclamation_of_the_Empire.jpg

Articles leveled by Newsela have been adjusted along several dimensions of text complexity including sentence structure, vocabulary and organization. The number followed by L indicates the Lexile measure of the article. For more information on Lexile measures and how they correspond to grade levels: www.lexile.com/educators/understanding-lexile-measures/

To learn more about Newsela, visit www.newsela.com/about.

The Lexile® Framework for Reading evaluates reading ability and text complexity on the same developmental scale. Unlike other measurement systems, the Lexile Framework determines reading ability based on actual assessments, rather than generalized age or grade levels. Recognized as the standard for matching readers with texts, tens of millions of students worldwide receive a Lexile measure that helps them find targeted readings from the more than 100 million articles, books and websites that have been measured. Lexile measures connect learners of all ages with resources at the right level of challenge and monitors their progress toward state and national proficiency standards. More information about the Lexile® Framework can be found at www.Lexile.com.