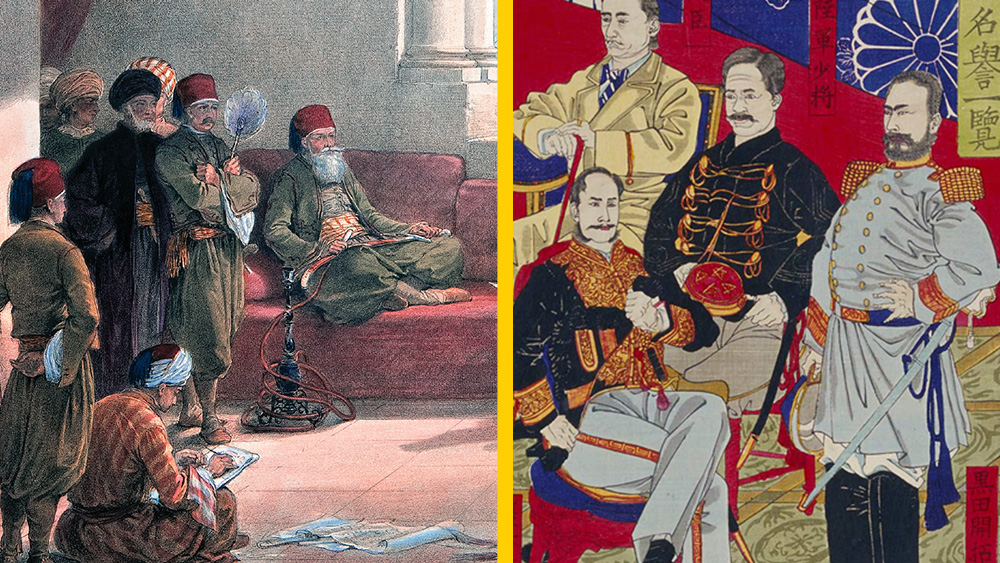

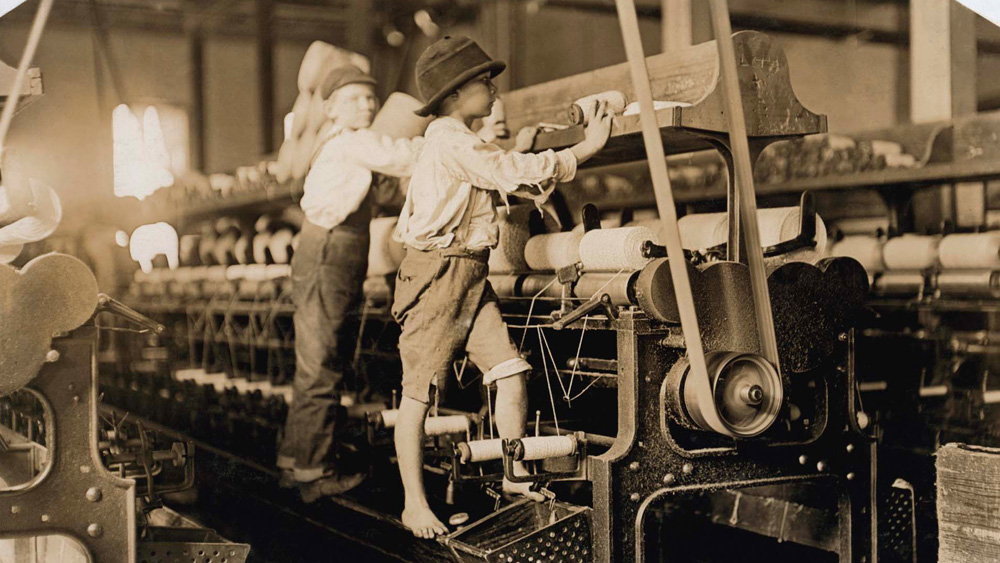

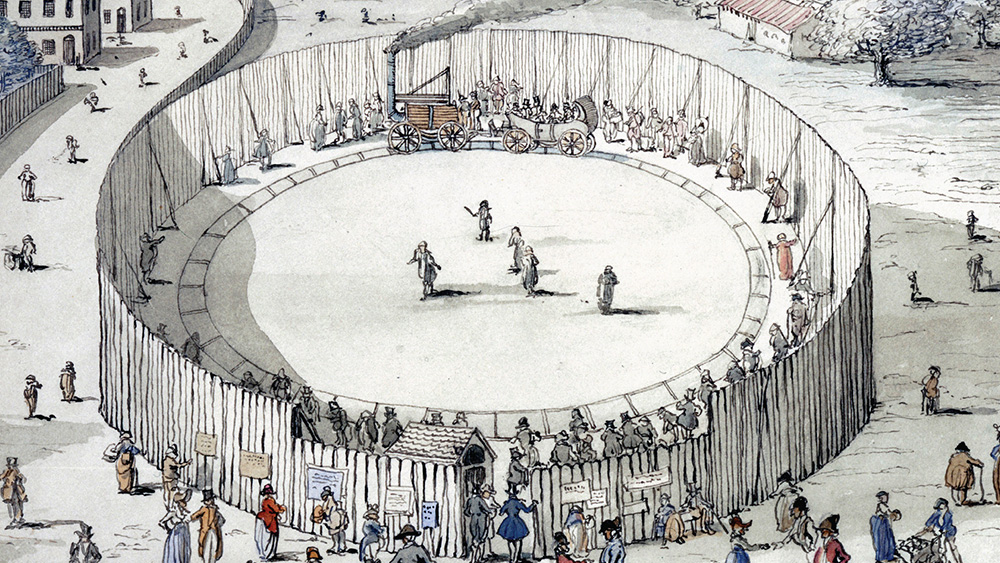

Unit 5: Revolutions

c. 1750 to 1900 CEBeginning in the eighteenth century, an age of revolutions shook the foundations of global power and industry. Enter an era of revolutionary ideas and innovations as new nations formed and new forms of production were created.

Lesson 5.0

Lesson 5.1

Lesson 5.2

Lesson 5.3

Lesson 5.4

Lesson 5.5

Lesson 5.6

Lesson 5.7

Lesson 5.8

Lesson 5.9

Lesson 5.10

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 5 Vocab

Key Unit 5 vocabulary words and definitions.

Using AI with OER Project

Transform your classroom with AI tools aligned to OER Project materials.

Activities Guide

Explore OER Project’s different activity types.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.

Skills Clinic: Teaching with Primary Sources

A teacher-driven session on incorporating primary sources into your instruction.

Unit 5 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.