Unit 4: Transoceanic Interconnections

c. 1450 to 1750 CEAfter 1492, transoceanic voyages linked the hemispheres in sustained connection for the first time, setting the stage for an exchange that forever changed the lives of people in Afro-Eurasia and the Americas.

Lesson 4.0

Transoceanic Connections

The linking of the Americas and Afro-Eurasia through the Columbian Exchange spread goods, people, ideas, and diseases around the world. How did new maritime empires control the oceans and shape the modern world?

Lesson 4.1

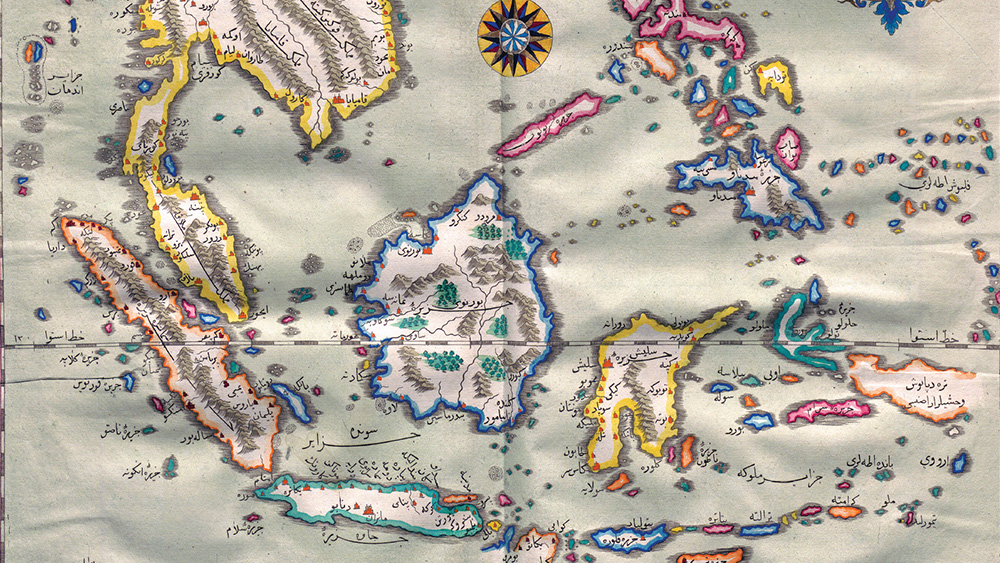

Technological Innovations from 1450 to 1750 CE

European exploration relied on Afro-Eurasian scientific advances, technology, and trade. Explore how centuries of knowledge sparked the first global age.

Lesson 4.2

Exploration: Causes and Events from 1450 to 1750 CE

Fifteenth-century European explorers used centuries’ worth of Afro-Eurasian knowledge and technology. Despite varied motives, mariners needed state support and resources for successful transoceanic voyages.

Lesson 4.3

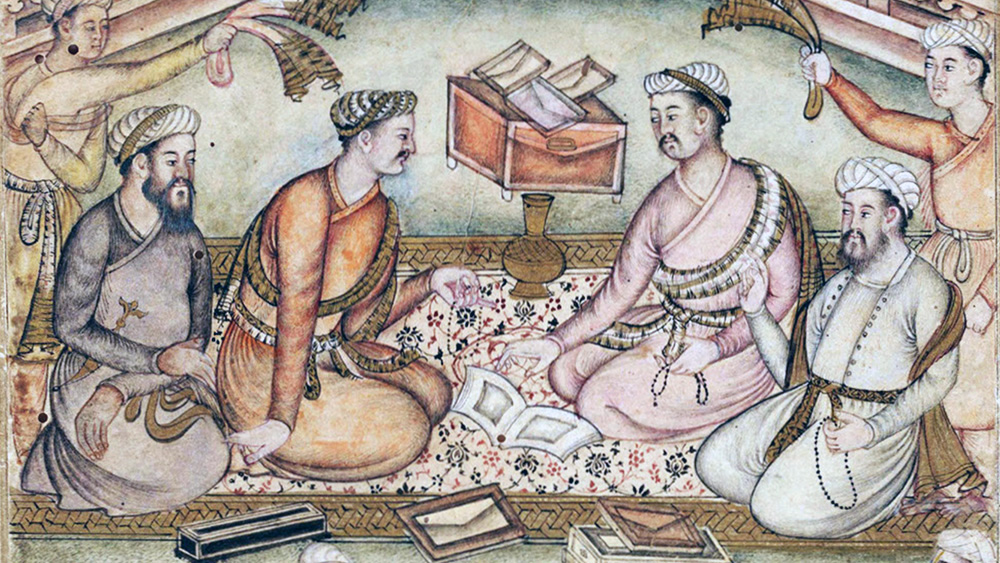

The Columbian Exchange

Complex exchange networks existed before Columbus, and the “New World” was an old home to Indigenous peoples. Still, new Afro-Eurasian-American connections forever reshaped life across continents.

Lesson 4.4

Maritime Empires Established

European exploration and colonization shifted from the establishment of small colonies to large empires. Their rise irreversibly transformed governments, economic systems, and social hierarchies.

Lesson 4.5

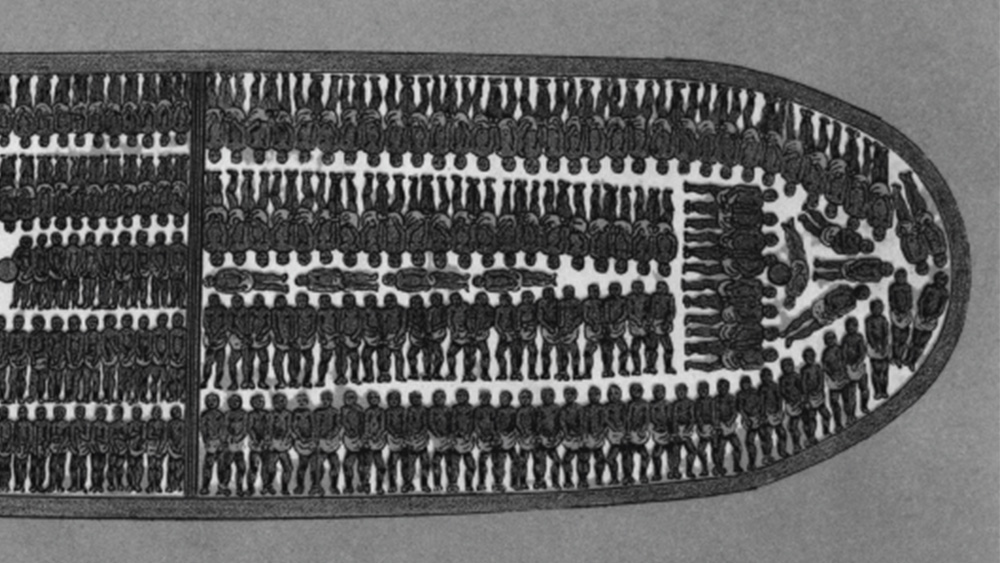

Maritime Empires Maintained and Developed

From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, labor and resources extracted from colonies built new economic systems that allowed maritime empires to expand their global power.

Lesson 4.6

Internal and External Challenges to State Power from 1450 to 1750 CE

As early modern empires expanded, states centralized power to maintain control. This often harmed those on the margins, inciting resistance from colonized people around the world.

Lesson 4.7

Changing Social Hierarchies from 1450 to 1750 CE

The new age of global exchange transformed economies, environments, and social structures around the world. Migration further shifted populations, pushing states to respond to these changes in various ways.

Lesson 4.8

Continuity and Change from 1450 to 1750 CE

You’re now ready to draw big-picture conclusions about this new global age! Decide what changed and what stayed the same as you evaluate how the Columbian Exchange impacted the Americas.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 4 Vocab

Key Unit 4 vocabulary words and definitions.

Reading Guide

Explore the types of texts in OER Project.

Video Guide

Tips for ensuring videos are engaging and instructive.

Writing One-Pager

Quick and easy strategies for incorporating informal writing frequently.

Historical Thinking Skills Guide

Develop the skills needed to analyze history and think like a historian.

Unit 4 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.