Unit 2: Networks of Exchange

c. 1200 to 1450 CEIf the world is indeed a tapestry, then networks of exchange were the threads that wove it together. See how the merchants who roamed these routes moved goods, ideas, and diseases across continents.

Lesson 2.0

Networks of Exchange

The year 1200 CE is a key starting point to explore how the world was organized before it became globally connected. Studying communities and networks from 1200 to 1450 helps us make historical comparisons across space and time.

Lesson 2.1

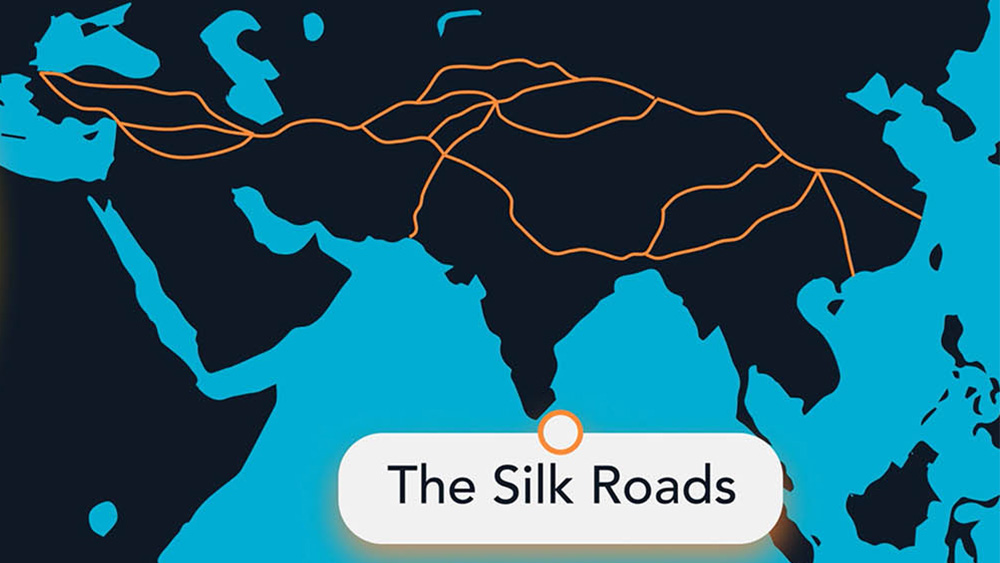

The Silk Roads

Explore the people, goods, and ideas that traveled along the Silk Roads from 1200 to 1450.

Lesson 2.2

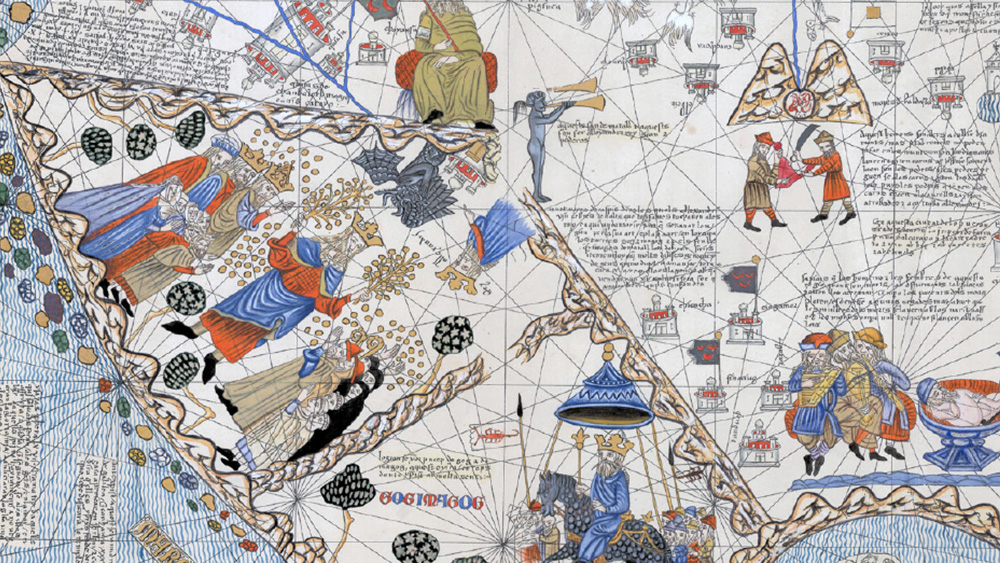

The Mongol Empire and the Making of the Modern World

Mongol nomads from Central Asia used unique methods to create the largest land empire in history. Their rule brought stability and security to the Silk Road routes, and trade flourished.

Lesson 2.3

Exchange in the Indian Ocean

Merchants crossed the Indian Ocean fueling the spread of new ideas and technologies across Afro-Eurasia.

Lesson 2.4

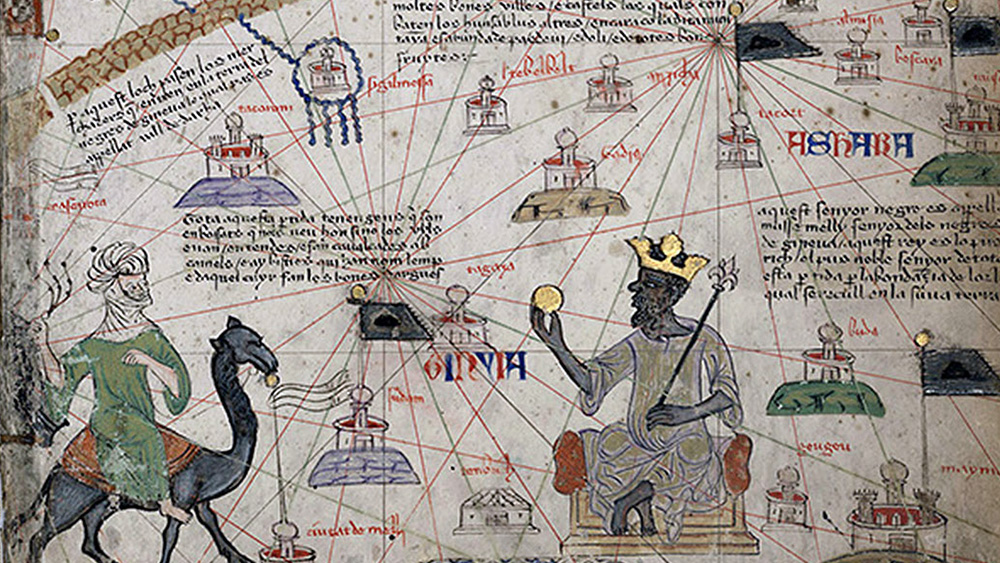

Trans-Saharan Trade Routes

Between 1200 and 1450 CE, Saharan trade routes connected West Africa to the Mediterranean. Camels enabled caravans to transport salt, gold, and people, spreading technology and Islam across the region.

Lesson 2.5

Cultural Consequences of Connectivity

From 1200 to 1450 CE, Afro-Eurasian exchange networks shaped culture and diffused knowledge. Contextualization skills will help you analyze and understand these cultural and intellectual changes.

Lesson 2.6

Environmental Consequences of Connectivity

Humans build communities to share goods, beliefs, and ideas across networks. While fourteenth-century connections spread innovations, they also brought challenges like the devastating Black Death.

Lesson 2.7

Comparison of Economic Exchange

Compare similarities and differences in exchange networks between 1200 and 1450 CE. Use historical thinking skills to analyze and evaluate these developments over time.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 2 Vocab

Key Unit 2 vocabulary words and definitions.

Reading Guide

Explore the types of texts in OER Project.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Writing Guide

Strategies for instructing and supporting both formal and informal writing.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.

Unit 2 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.