Unit 2: Early Humans

250,000 years BP – 3,000 BCEFor most of our 250,000-year history, all humans were foragers. But then, about 12,000 years ago, some people started farming. Was it all a huge mistake?

Paleolithic Humans

Lesson 2.2

Migration and Art

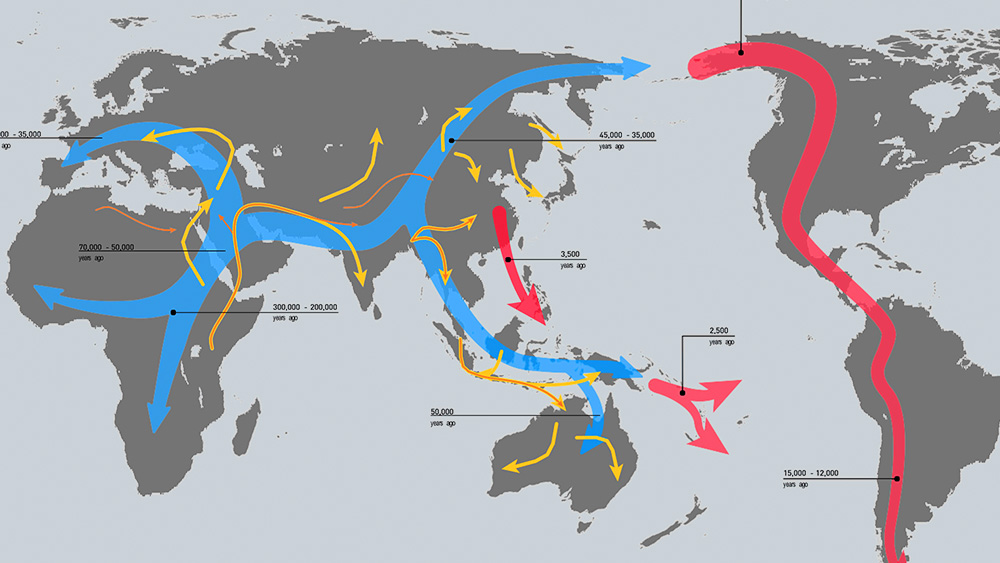

Why did early humans move to new places and create art during this period? Dig into 80,000-year-old evidence to answer this question.

Lesson 2.3

Foraging Societies

Hunting and gathering required great knowledge and skill. How did these skills help foragers thrive for hundreds of thousands of years?

Neolithic Revolution

Lesson 2.4

The Agricultural Revolution

How smooth was the transition between foraging and agriculture? Explore why the Agricultural Revolution began, and analyze the pros and cons of this revolutionary shift.

Lesson 2.5

The Biggest Mistake Humans Ever Made?

Was the development of agriculture good or bad? Investigate the consequences—both positive and negative—of farming for humanity.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 2 Vocab

Key Unit 2 vocabulary words and definitions.

Reading Guide

Explore the types of texts in OER Project.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Writing Guide

Strategies for instructing and supporting both formal and informal writing.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.

Unit 2 Teaching Guide

All the lesson guides you need in one place.