Unit 7: The Long Nineteenth Century

1750 to 1914 CEThe long nineteenth century transformed how people understood childhood, work, gender, and the very concept of human liberty. Driven by new ideas and new machines, this 164-year period created the world we live in today.

Liberal Revolutions and Nationalism

Lesson 7.2

Enlightenment and Revolution

Discover the ways Enlightenment thinkers challenged old ideas and inspired revolutions that reshaped politics, rights, and society across the globe.

Lesson 7.3

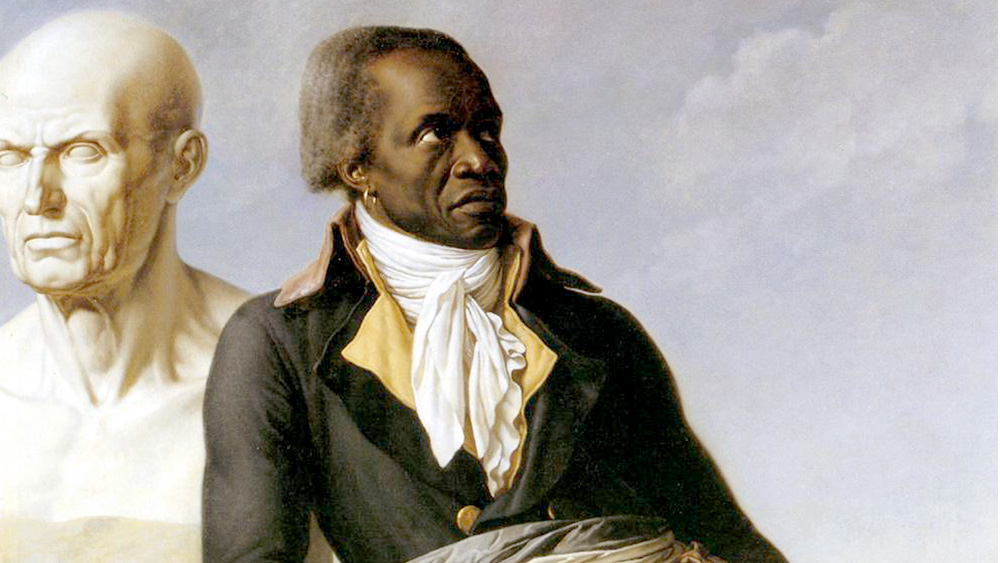

Atlantic Revolutions

What made the Age of Revolution revolutionary? Examine the root causes and consequences of revolutions across the Atlantic world.

Lesson 7.4

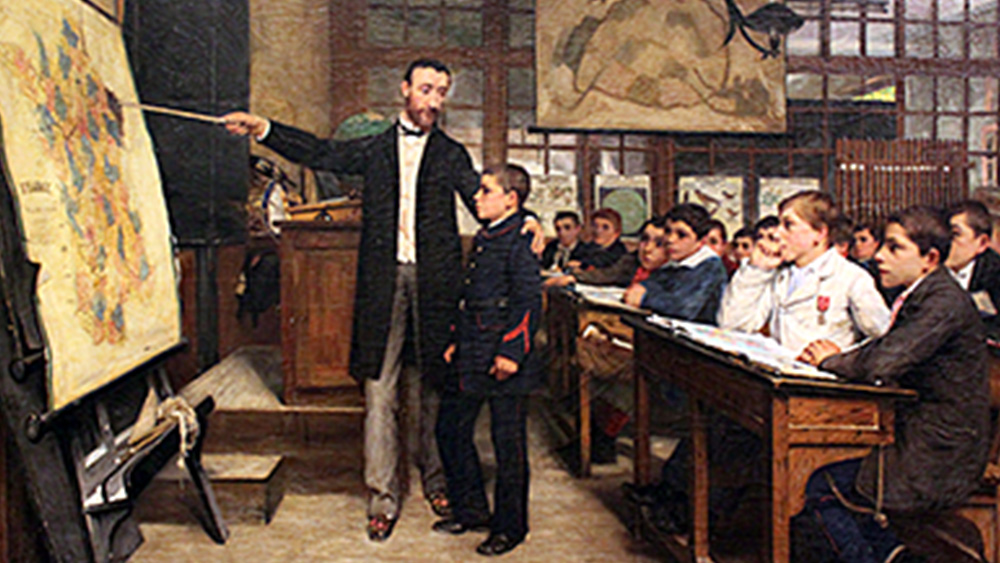

Nationalism

Trace the rise of nationalism to see how it emerged, spread, and fueled revolutions and new identities—shaping the world of nation-states we know today.

Industrialization

Lesson 7.5

The Industrial Revolution

Explore how the Industrial Revolution began, spread, and transformed cities, labor, and technology around the world.

Lesson 7.6

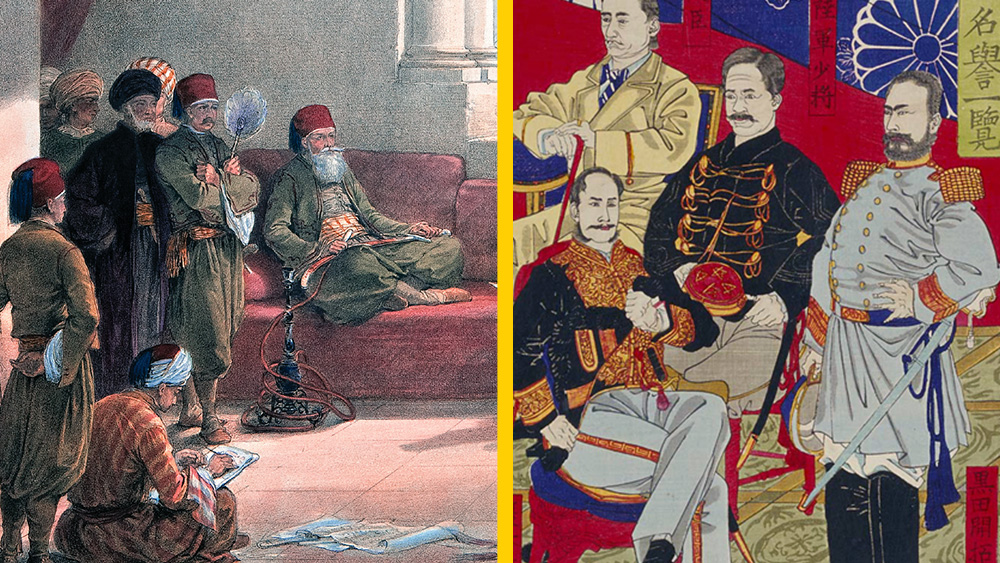

Comparing Industrialization in Egypt and Japan

Industrialization took different forms across the globe. Compare how Egypt and Japan responded to industrialization and explore why their paths and outcomes were so different.

Reform Movements

Lesson 7.7

The Working Class

How did workers respond to industrialization? Explore how industrialization shaped the working class and sparked new ideas, movements, and responses to economic inequality.

Lesson 7.8

Reform Movements

Industrialization raised new questions about equality and human rights. Consider how industrialization sparked global calls for reform, from abolition to labor rights to women’s suffrage.

Colonization and Resistance

Lesson 7.9

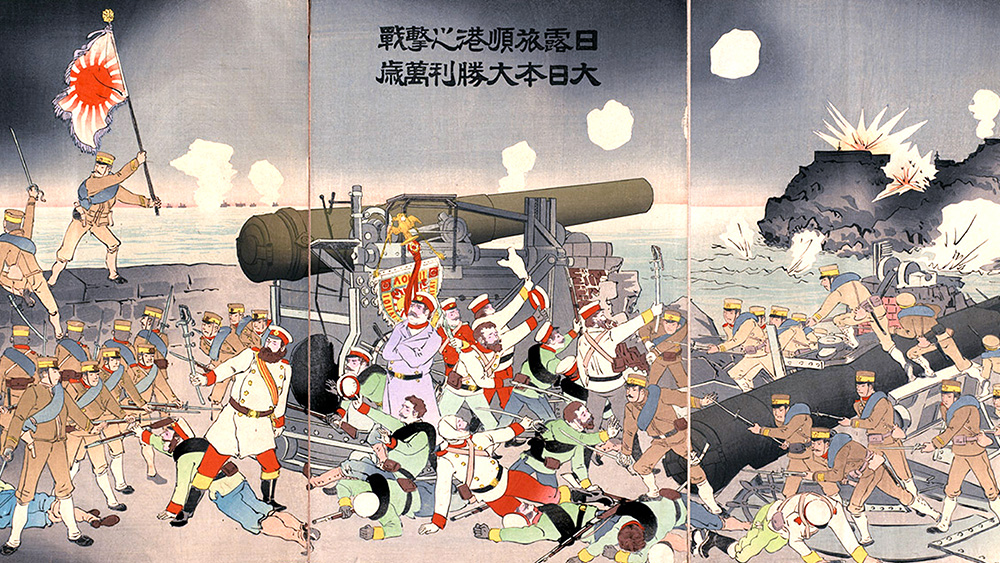

Industrial Imperialism

Empires were nothing new—but industrialization transformed them. Discover how industrialization fueled imperial expansion, reshaped global economies, and sparked conflict and resistance worldwide.

Lesson 7.10

Resisting Colonialism

Wherever empires expanded, colonized peoples pushed back. Explore resistance in all its forms—from uprisings and powerful leaders to everyday acts of defiance and resilience.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Graphic Bios Guide

How to incorporate graphic biographies into the classroom.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Assessment Guide

Learn about OER Project’s approach to assessment.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.