Unit 7: Global Conflict

c. 1900 to the presentThe transformations of the long nineteenth century set the stage for an era of unprecedented warfare, atrocity, and threat to our species’ survival.

Lesson 7.0

Global Conflict

The early twentieth century saw two devastating world wars that caused massive destruction. Nations, societies, and economies were upended worldwide. This era reshaped global history.

Lesson 7.1

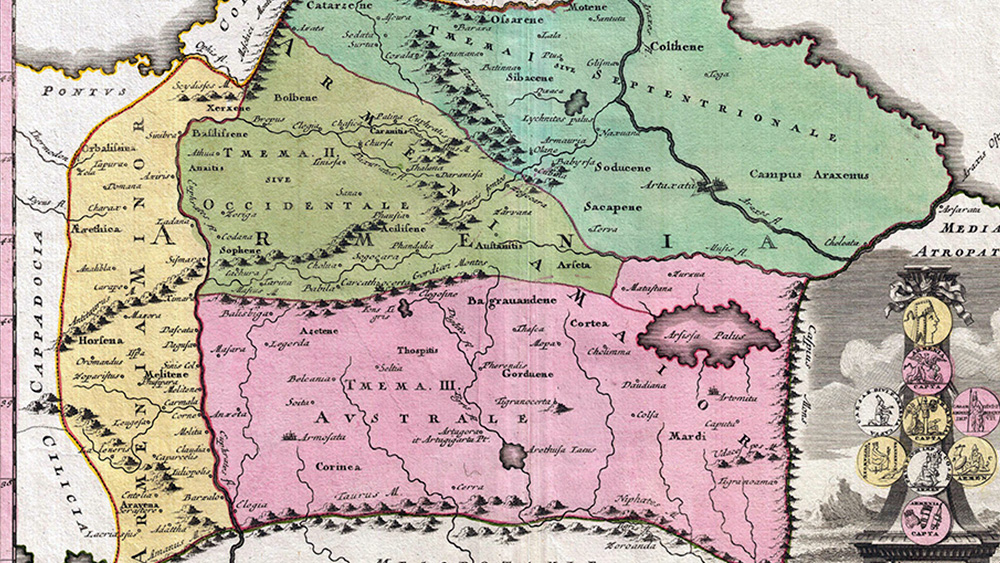

Shifting Power After 1900 CE

In the long nineteenth century, industrialization and colonialism enriched a new ruling class. By the early 1900s, workers worldwide challenged this power, agitating for social and political change.

Lesson 7.2

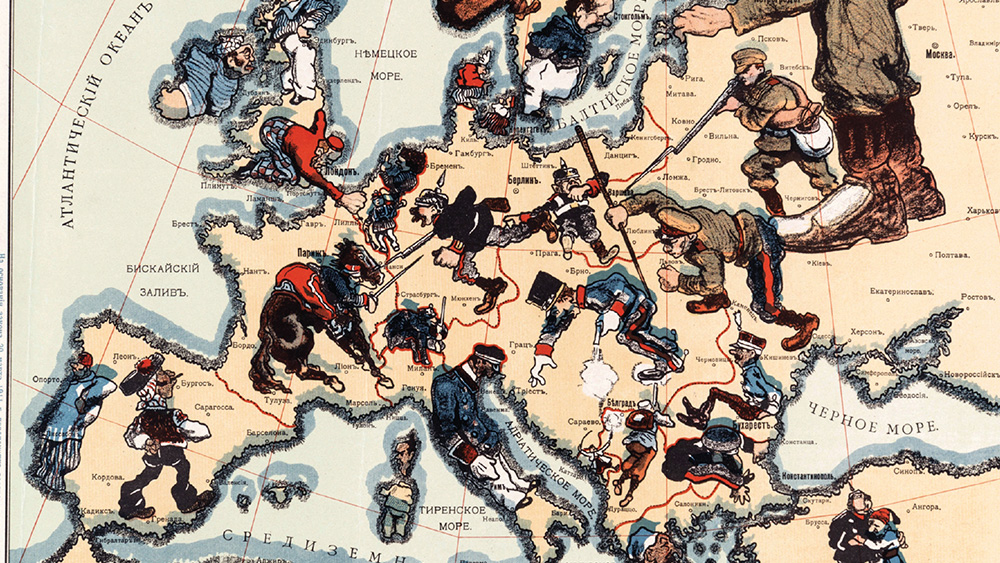

Causes of World War I

The First World War had multiple causes—political, ideological, economic, and social—that developed during the long nineteenth century and culminated in a complex conflict that lasted from 1914 to 1918.

Lesson 7.3

Conducting World War I

The First World War began in Europe’s empires but quickly involved nations and colonies across the entire world. New weapons and massive mobilization made it the first truly global conflict.

Lesson 7.4

The Economy in the Interwar Period

The 1929 US stock-market crash triggered a global depression due to growing economic interdependence. Nations reacted differently, with many states gaining power and some turning toward authoritarian rule.

Lesson 7.5

Unresolved Tensions After World War I

Many hoped for a lasting peace after World War I, , but harsh war punishments and territorial disputes fueled tensions, setting the stage for future conflict.

Lesson 7.6

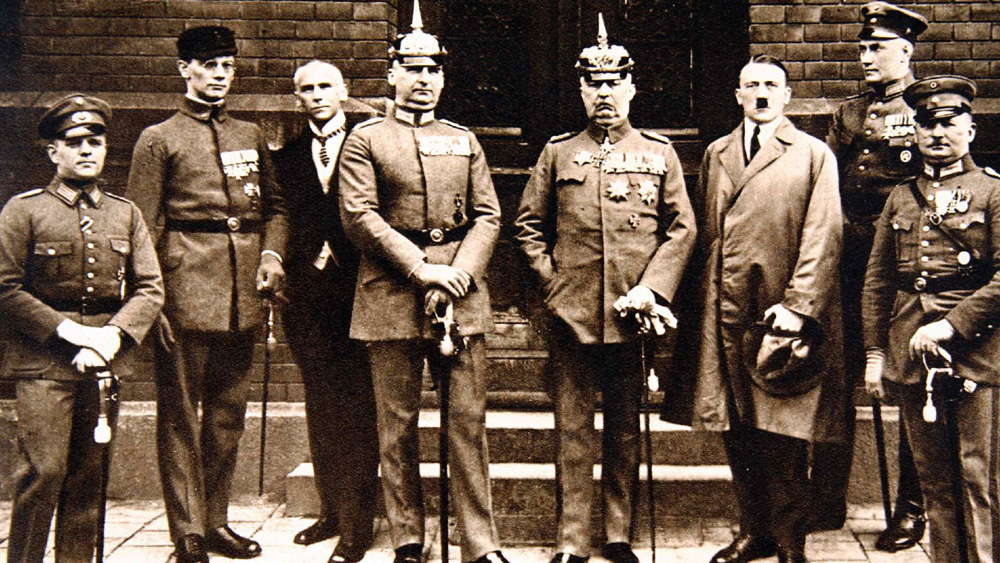

Causes of World War II

The rise of fascism and failure of internationalism ended the fragile peace that followed the First World War. The Second World War was to be the deadliest war in history—and it changed humanity forever.

Lesson 7.7

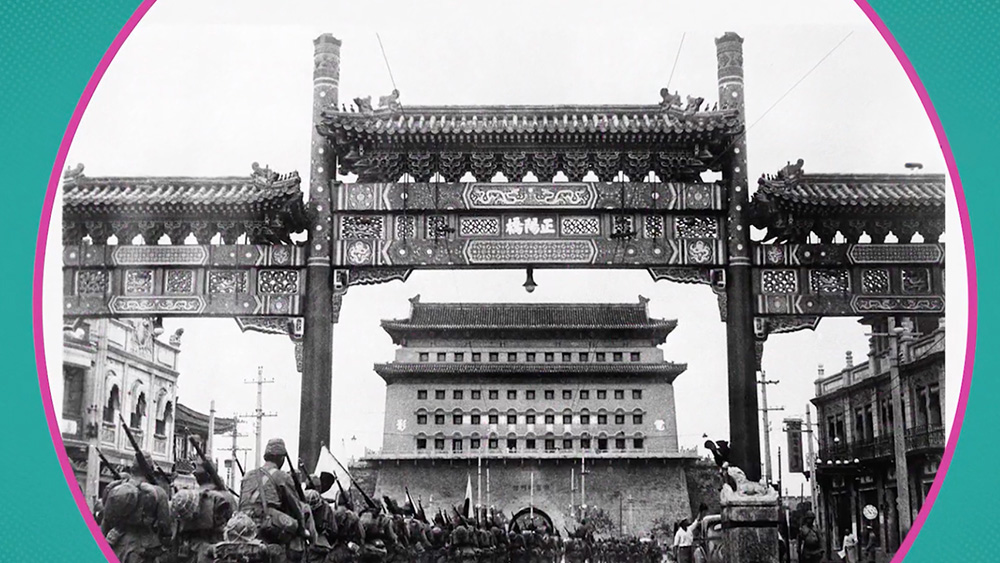

Conducting World War II

Twenty years after the First World War, the another, even deadlier world war erupted. New tactics and technology made the Second World War even more destructive and devastating than the first global conflict.

Lesson 7.8

Mass Atrocities After 1900

World War II and the Holocaust caused immeasurable loss. The war also accelerated movements against colonialism, as new mass atrocities took place during wars of independence.

Lesson 7.9

Causation in Global Conflict

Analyze and revise essays focusing on evidence, sourcing, and complexity. Connect unit themes by examining the Nazi Party’s rise in Germany through a DBQ that demonstrates your understanding.

Teaching This Unit

Teaching This Unit

Unit 7 Vocab

Key Unit 7 vocabulary words and definitions.

Graphic Bios Guide

How to incorporate graphic biographies into the classroom.

Vocabulary Guide

Strategies and routines for building vocabulary.

Assessment Guide

Learn about OER Project’s approach to assessment.

Data Literacy Guide

Clear, concise strategies to help teach data literacy and build student confidence with data visualizations.

Unit 7 Teaching Guides

All the lesson guides you need in one place.